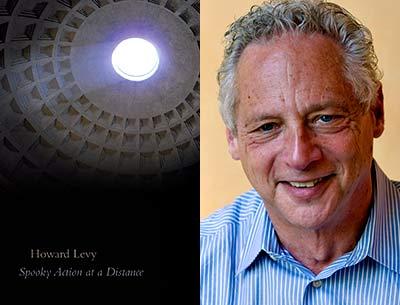

Particle Love

“Spooky Action

at a Distance”

Howard Levy

CavanKerry Press, $16

Do the laws that govern the physical universe also govern human behavior? “Spooky Action at a Distance,” the title of Howard Levy’s new book of poems, was Einstein’s retort to physicists explaining quantum mechanics. In “The Age of Entanglement,” Louisa Gilder explains that Einstein scoffed at the idea that “Two particles that had once interacted could no matter how far apart remain entangled.” Think of identical twins claiming to feel each other’s pain even continents apart.

Or think, as Howard Levy apparently does, about lovers; his title poem, for example, employs quantum mechanics as a powerful metaphysical conceit for love, for the energy that binds two people together. Elsewhere in this collection, however, Mr. Levy decidedly sides with Einstein, who couldn’t fathom that particles were not independent, incapable of acting separately.

Many of Mr. Levy’s speakers feel alienated from the natural world. In these poems, whatever force holds people in love together has disappeared, and Mr. Levy’s speakers try, more often than not unsuccessfully, to feel conjoined to the world through which they move. Readers of “Spooky Action at a Distance” will need to decide if Mr. Levy believes people are subject to the same laws that hold the universe together or if we move independently through the world, striving to feel connected.

In the title poem, the speaker sets readers up for this comparison of love as entanglement (in the quantum mechanics sense) with the first lines:

It is this way: men and women

spin. Hundreds of miles apart, thousands

of miles, the speed of light, it will make no difference.

Mr. Levy establishes lovers as particles, neither of which remains unaffected by action taken toward each other. The speaker details what two people are doing simultaneously “across a continent.” A woman puts on a man’s shirt, and the man is able to see this happen with his imagination. Mr. Levy’s speaker tells us that “Such is the quanta of intimacy,” convincingly establishing this lovely trope of human being as particle that is further explored in the following stanzas.

But Mr. Levy’s poems move the other way, too. His speakers, when not musing on love, appear cut off from the world they inhabit, aware of the disconnect consciousness creates between external nature and mind. In “Why I Get Up Early,” for instance, the speaker walks the beach, taking in the beauty of sunrise and two deer atop a dune:

They watch me as I walk,

their attention has fixed me

into this scene. Here. Now

including me.

I have had such difficulty

ever feeling that.

This speaker admits his psychic distance from the natural world and the difficulties of living in the moment. The poem’s last two emotive lines, quoted above, explode with the force and surprise of something James Wright or Robert Bly might have written.

Other poems of disentanglement in this collection include “Indian Wells, December,” “#9, Again,” “He Wakes Up at Three A.M.,” and “Not Feeling.” All of these poems concern themselves with a sensation of not belonging, of restlessness, of inarticulateness in the face of nature. Mr. Levy’s speakers are Adams, cast out from the garden, unable to return to Eden and to make sense as to why they feel so disenfranchised. Here are the final two stanzas of “Not Feeling”:

Not feeling a single thing about light or splendor,

no extolling of God’s work

and no extolling randomness,

not at all amazed that accident

could arrive at this

but seizing on how emptiness

shapes itself into a roof

and how I remain fixed in shadow

even here

even here in this blazing place.

It’s clear that this speaker, confronted by God’s handiwork, finds himself incapable of praise. We’ve come a long way from the interconnected lovers as particles and arrived at a speaker experiencing a keen sense of isolation, unaffected by nature’s beauty.

This alternation between two metaphorical takes on quantum mechanics creates the tension in this collection. Mr. Levy is at his best in short poems where he stretches his sentences over many lines, frequently enjambed, creating a rhythmical intensity propelling his poems down the page, as in “Prostate Cancer” and “Divorce: The Improvisation.”

But Mr. Levy exhibits a bit of trouble handling some of his longer poems. In these poems, such as “Questions for Baron” or “Indian Wells Diptych,” he appears to be trying too hard to convince his readers of the validity of his perceptions. For instance, in “Questions for Baron,” he writes:

I remember reading

that the OED says the word “lonely”

first appears in Shakespeare, Coriolanus.

How could that be possible?

Can you imagine this a modern, evolved condition,

an adaptation that enhances the possibility

of survival? I don’t know how

but, if so, what a horrible thought.

Aside from the fact that this passage seems like flat prose broken into lines that resemble poetry, readers may resent the speaker telling them how to feel about the subject matter. This happens perhaps a bit too often in this collection; Mr. Levy’s poems might be even more effective were he better able to preserve their sense of the inexplicable.

Finally, it appears that Mr. Levy too often lapses into use of the pathetic fallacy or strains too hard to create certain effects. “Indian Wells Diptych” features both of these miscues. Examine, for example, these lines:

The sky is all blue signature but the moon

hangs visible, very pale, as if used up,

exhausted, shaken

from the exertion of last night’s shining.

Besides the fact that it is impossible for the moon to be “used up,” note the way Mr. Levy tries to make sure we don’t miss this — he employs “used up,” follows it with “exhausted,” and piles it on with yet another line that means the same thing, “shaken / from the exertion of last night’s shining.” Does the moon exert itself?

Later, near the end of the same poem, Mr. Levy writes of the ducks his speaker is observing that “they can wonder, in their fine duck way.” I’m uncertain it’s a poetic virtue to posit an understanding of the manner in which ducks “wonder,” and if, in fact, that manner is “fine.”

In general, I found much to admire in this collection. Howard Levy writes with great sensitivity about human relationships using strong imagery and some wonderful metaphors. The fact that a few of these poems might have benefited from more careful editing does not diminish or detract from the overall efficacy of “Spooky Action at a Distance.” Perhaps Einstein would have enjoyed it; perhaps you will, too.

Dan Giancola is a professor of English at Suffolk Community College. His collections of poems include “Data Error” and “Part Mirth, Part Murder.”

Howard Levy’s work has appeared in Poetry, Threepenny Review, and The Gettysburg Review. He lives part time in Springs.