‘Pollock’s Paper Trail’ a Highlight of Recent NYC Ab-Ex Symposium

A recent symposium in Manhattan brought together scholars from around the country and across the Atlantic to study “Abstract Expressionism: Works on Paper.” One of the more interesting and revealing presentations came from Helen Harrison, the director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs, which was a co-presenter of the program with the Clyfford Still Museum and Stony Brook University.

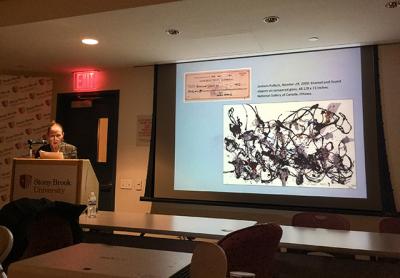

Her talk on “Pollock’s Paper Trail” took an interpretive dive into the check stubs and ledger books of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner from 1946, soon after their arrival in Springs, to 1954.

“I’m going to take on the role of Deep Throat from ‘All the President’s Men’ here and find out what was going on with Jackson Pollock during this period by following the money,” she told her distinguished audience.

Ms. Harrison noted that Krasner’s will instructed her trustees to establish a foundation that would run the house as a public museum and study center. After she died, in 1984, the house was left intact; three years later, it was deeded to the Stony Brook Foundation.

Inside the house were two previously unknown drawings by Pollock on restaurant placemats, and a suitcase that had belonged to Alfonso Ossorio, a fellow artist and friend of the couple who was the longtime owner of the Creeks, a 60-acre estate in East Hampton. While the suitcase itself was a significant find, its contents — the financial documents featured in Ms. Harrison’s talk — were of far more interest.

In 1946, Krasner opened a bank account at the Osborne Trust Company in East Hampton in her married name, Lee Krasner Pollock. She and Pollock had married during the preceding October before making Springs their primary residence. Since Pollock was making all the money at the time, Ms. Harrison raised the question of why it should have been his wife’s name alone on the account. It was reasonable to assume, she said, that it was because of Pollock’s drinking.

He was treated, successfully, by Dr. Edwin Heller, a general practitioner here whose name appears on check stubs from the summer of 1948. That November, Krasner finally put Pollock on the bank account. After Dr. Heller’s death in a car accident in March 1950, Pollock went back to drinking, but his name stayed on the account.

The checks he signed that were projected on the screen were somewhat jarring. Pollock’s iconic signature on pieces of paper sent to plumbers, carpenters, and other tradespeople looked almost absurd. It seemed far more congruous to see his signature on the numerous checks he wrote to artists over the years, including Mark Rothko, Bradley Walker Tomlin, James Brooks, and Clyfford Still, in amounts ranging from $20 to $150. It is tempting to wonder what those payments were for — a repayment of loans for art supplies, or, since most were dated 1950 or later, a way to hide his bar tabs?

The checks and ledgers also recorded the couple’s monthly mortgage payments — $37.98 — for their Springs house. Peggy Guggenheim loaned them the $2,000 down payment on its $5,000 purchase price, and $157 was paid for furniture and other things that were left behind by the previous owner. Ms. Harrison described the loan contract, which stipulated that Pollock’s patron would have exclusive right to his paintings for two years, except for one painting that he could keep for himself. He also received a monthly allowance of $300 against sales, of which $50 was held back to repay the loan.

This “complicated arrangement” seems punitive now, she said, “but at the time Jackson Pollock was unknown.” Once the loan was repaid, artist and collector returned to their original compensation arrangement, established in 1943 when she first showed his work at her New York gallery, Art of This Century. That earlier agreement stipulated that she would receive a third of the purchase price of his works.

The financial documents were paired with the artwork Pollock created from those purchases. Ink-soaked drawings on Howell paper appeared with an image of the check Pollock wrote for the cost of the paper. His 1950 glass painting “No. 29,” shown in a film by Hans Namuth, who captures the application of the paint from the other side, was shown with a check for $30 to the Riverhead Glass Company. Ms. Harrison also included this newspaper’s account of the artist’s death in 1956.

Jennifer Field, another presenter, also referenced “No. 29” in her talk on the influence of printmaking in Pollock’s art. She said the glass painting could be seen as a printing plate or mirror of itself, a theme taken from gestalt psychology and popular in the studio of Stanley William Hayter.

Hayter was an avant-garde printmaker who opened a studio at the New School in 1940 after running a collaborative workshop in Paris for many years. Many of the Abstract Expressionist artists, who worked alone all day in the studio, liked the social side of making prints. Hayter’s insistence that they work directly on the printing plate or lithographic stone, rather than making preparatory drawings, and work in a completely abstract or experimental style, also attracted them.

David Acton, who spoke about printmaking and Abstract Expressionism, said that Willem de Kooning, another longtime Springs resident, was inspired in Hayter’s studio to use a mop to draw in wet touche (a kind of ink) on a stone, making a composition which he then ran through a press. Pollock and Reuben Kadish, said Mr. Acton, would spend “long drunken nights in the studio making prints together.” Those prints were not intended to be sold, but as experimental exercises.

Richard Shiff, a professor at the University of Texas, offered a talk that described itself in its title, “De Kooning Is Drawing.” He argued that even when the artist was painting he was drawing, in a style that Pablo Picasso may have called “melted Picasso.”

Other artists associated with the South Fork who were referenced in the all-day event included Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, and Franz Kline. The symposium, which took place in space leased by Stony Brook University, was the last such event to be held there under the school’s banner. It will close the space at the end of this month.