The Power of the Picture in Shaping Our Politics

The media, particularly cable news, loves the horse-race aspect of elections, so much so that they devote hours of airtime to the speculation of who will run for president five minutes after the current president has been inaugurated. This election cycle brought the usual frenzy, but then it trebled with the announcement last year that Donald Trump would run.

Flouting all of the rules that have traditionally applied to campaign management, Mr. Trump refused to edit himself and let loose a wave of outrageous soundbites and tweets while the media breathlessly and enthusiastically reported each one. For once, a campaign was not going according to script and it was fun. The whole experience of the past year, while entertaining, can make one long for the old days, both the good and the bad.

And that is what we find at the Southampton Arts Center with the International Center of Photography’s exhibition “Winning the White House: From Press Prints to Selfies.” The exhibition, organized by Susan Carlson and Claartje van Dijk, examines how modern media has shaped elections from 1960 to the present in still and video photography.

The show offers sometimes astonishing context for how the public has absorbed the information it uses to make these important decisions. It begins in 1960, because that was the year it became clear that an election could be won through what is now called optics. In one famous debate, Richard Nixon perspired and looked uncomfortable on camera while John F. Kennedy was smooth and polished, and easily more attractive. Historians have noted that those listening to the debate on the radio thought Nixon had won, but with 88 percent of American households with televisions at that time, all of which were likely tuned in, Kennedy’s appearance won out over the substance of what was said.

It was a watershed moment, the first time the relatively new medium (only 11 percent of households had a television in 1950, according to the exhibition’s wall text) was clearly seen to have played a role in an election’s outcome. The exhibition has both stills from the campaign and video from the debates that show Kennedy and Nixon doing their best to project a presidential image.

Although the idea of what was presidential shifted over the years, starting with Jimmy Carter’s more casual and rumpled peanut farmer look, some themes have endured. A poster in the introduction to the exhibition tells us that Gerald Ford, who was the Republican nominee in 1976, was going to make us proud again after the Vietnam War and Watergate.

Republicans not only owned pride and patriotism for many years, they also cornered the market on strength with their plainspoken declarations of American invincibility and their avid support for military spending. During the 1980s, Ronald Reagan and his image makers like Lee Atwater embraced thetough guy stance in dealing with foreign affairs. In response, Michael Dukakis, who ran against George H.W. Bush in 1988, felt pressure to show that Democrats were not weak. The resulting photo op of Mr. Dukakis riding around in a tank with a personalized helmet did not go over well. Reporters covering the event laughed, some even doubled over, and the public found it no less amusing.

To many commentators and strategists, it was the day he lost the election, and to have a “Dukakis in the tank” moment became shorthand for a variety of image-related mistakes. The exhibition provides a record of memorable images from that election period: Reagan pointing at the Statue of Liberty at a campaign stop and holding up an old ad he had done for Van Heusen shirts. Dukakis in the tank is also here, looking as ridiculous now as he looked then.

Television helped candidates raise their profiles and to seem with it, as when Nixon went on “Laugh-In” to say the show’s tagline, “Sock it to me.” “Saturday Night Live” took aspects of the president’s character and blew them up large: Ford’s tendency to trip down stairs or hit his head on plane doors. Chevy Chase managed to become addicted to painkillers from the actual injuries he sustained while playing that role. Dan Aykroyd’s Carter skits included him guiding someone through a bad acid trip on a call-in show, making him seem like some kind of shaman genius, a reflection of Carter’s strong intellect.

Cable television fractured viewership for once must-see events like conventions and debates, and the candidates themselves found they needed to find ways to grab the attention of a broader population. Stills of Bill Clinton playing saxophone on Arsenio Hall’s show and of Ross Perot during his one-hour ad buy to discuss his economic plans for the country document that shift during the 1992 election.

The advent of the internet and then social media gave the public more direct and immediate access to candidates and the people who cover them. The past three elections have been dominated by selfie culture, where getting a picture with someone’s baby is much more important than kissing them.

Candidates and their handlers have had to adapt by managing the circumstances in which such activity takes place, if not the image itself. Carefully planned photo ops still exist, but it’s often the unguarded moments that go viral. The image of Hillary Clinton looking very in charge as secretary of state on her cellphone comes to mind, a meme that still pops up now and then.

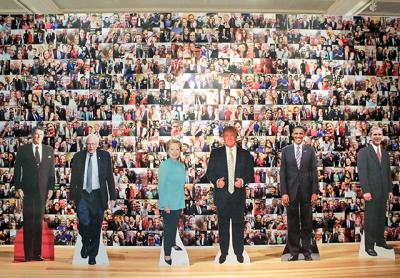

This shift is celebrated in the selfie wall at the entrance to the rear gallery. Behind life-size cutout figures of current and recent presidents and candidates, where visitors can craft their own portraits, are scores of cellphone pictures taken with actual candidates, images easy enough to find with an Instagram account. They tell the story of how these months will be remembered. They are rounded out by the professional and artful capturing of Mr. Trump’s acceptance speech from above the lectern by Mike J. Terrill, or J. Scott Applewhite’s image of the balloon monsoon that greeted Hillary after her acceptance speech.

For anyone who remembers the International Center of Photography’s history and its founding by Cornell Capa in 1974 as an outlet for “concerned photography,” the three images by him in the show from the 1960 presidential campaign are a reminder of the center’s noble genesis. Other photographers in the show include Grey Villet, Elliott Erwitt, Mark Bussell, Chris Buck, Stephen Crowley, Ken Light, Mark Peterson, Antoni Muntadas, and Marshall Reese.

They offer a beacon of serious journalism that continues, while many have come to see world leaders only as celebrities and catastrophic events chiefly in terms of how they relate to themselves.

The show remains on view through Sept. 11.