Radical Descent . . . Into What?

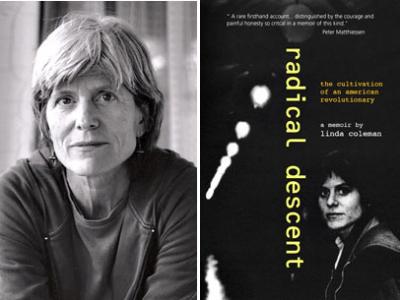

“Radical Descent”

Linda Coleman

Pushcart, $18

At first glance, Linda Coleman’s “Radical Descent: The Cultivation of an American Revolutionary” looks like another entry in a familiar genre: confessions of a late-1960s, early-1970s radical leftist.

You know the story. Twenty-something baby boomer out to change the world, right the wrongs, save the planet, end the (Vietnam) war, and emancipate the poor realizes that marching for peace won’t do the trick when the cops have more guns and are willing to use them and tear gas against you and your fellow hippies.

I’ve made the argument myself: Political and economic elites, people who have more power and money than the rest of us, 1-percenters in the parlance of the late, not so great, Occupy Wall Street movement, will never relinquish their prerogatives or their privileges or their cash just because we ask politely or because it’s the right thing to do. Theirs is a system, gangster capitalism, that is unspeakably violent, militaristic, and brutal in every way; it only stands to reason that adhering to strictly nonviolent tactics will not, cannot, and indeed never has worked in effecting radical, revolutionary change.

The kind of progress that Linda Coleman and her comrades in groups like the Weather Underground and Students for a Democratic Society sought was wholesale change on the scale — though not necessarily executed the same way or with the same desired results — of the uprisings that toppled the governments of France in 1793, Russia in 1917, and China in 1949. Under this radical vision, those who are rich will no longer be rich, those who are poor will no longer be poor, those who are in charge will no longer be in charge, those who are not in charge will be in charge.

Ms. Coleman is a member of the last American generation whose left included a significant number of activists who craved revolution, real revolution, and came to the conclusion that violence would be necessary in order to effect it.

Ms. Coleman’s political awakening, though percolating for years beforehand, occurs at a leftist bookstore in Portland, Me. “Every day that passes I learn more about the way power works in this country, what color you have to be, what sex, what class or religion to have a place at the table, the dining room table. Otherwise, you eat in the kitchen. You eat leftovers if you eat at all. Every day my commitment to become a revolutionary deepens.”

She decides to act. She joins an obscure revolutionary cell. Like many of her comrades, Ms. Coleman is bourgeois. And she feels guilty about it.

And weak. Referring to Che’s classic appeal to the revolutionary to love, “I thought about how there was something . . . lacking in me, something I had to change. To be revolutionary, I couldn’t just love, I had to let the hate in too.”

Much of “Radical Descent” is dedicated to Ms. Coleman’s failed attempts to mimic the hardened men with whom she falls in, a group of criminals who rob banks in the name of the revolution but in truth lead no movement, have no connection to the masses, and commit the most grievous sin someone who seeks to emancipate the human race can possibly commit: Rather than follow the people, they run off half cocked, doing whatever the hell they feel like while wrapping their crimes in the veneer of radical action.

When I read or watch accounts of small groups like the Weather Underground and the Red Army Faction, I am usually frustrated by the absence of basic Marxist analysis at the time, or even now.

No one can jump-start a revolution. Revolutionary situations require a witches’ brew of state oppression, economic despair, and bourgeois sympathy triggered by self-interested frustration with their own inability to advance their station in society, among other factors. The fact that none of those basic conditions existed in the late 1960s or the early 1970s in the United States, when leftist radicals were robbing banks and hijacking planes and blowing up draft offices, ought to have been obvious to anyone who had cracked open a copy of anything by Mao or Lenin.

Anyway, didn’t any of these people ever look behind and see that nobody was following them? After the big S.D.S. split of 1968 and the failure of the uprisings at Columbia University and in Paris and Tokyo, the students who led those movements splintered off into the work force to become cogs in the corporate machine, buy cars, and finally buy houses in the suburbs where they settled to raise their families.

Demographic and political realities of the time, and the failure to assess them, were the real errors of the 1970s radical left. To Ms. Coleman, however, the mistakes were personal. Men in the movement abused and even raped women. The money from bank robberies and from her trust fund — her comrades kept asking for donations — vanished into who knows what. They were, well, jerks.

A book should be judged by the intent of its author, but this otherwise well-written book doesn’t seem to exist to deliver a coherent message. It’s a memoir, a window into a time and a movement, and about as brilliant a description of an idealistic young woman’s confusion as I’ve ever read. But there’s too much personal narrative, not enough politics — and I don’t care to re-enact anyone else’s confusion.

In the end, the feds nail Ms. Coleman. Threatened with prison unless she betrays her former comrades, she testifies against them. “I’d go to jail. For as long as it took. At least I would have a righteous foot to stand on when I got out, if I got out. Had I been alone, I’m certain that’s exactly what I would’ve done. But I wasn’t alone. I was newly married. And then I was pregnant, and that changed everything. . . . There was no choice left at all.”

Having not had cops up my ass, perhaps I shouldn’t judge Ms. Coleman’s caving. But that’s what leftists do: We judge. Ms. Coleman wrote that Nelson Rockefeller deserved to die for policies that sent countless young men and women to jail, and here I will write that Ms. Coleman lied when she said she had no choice. She made her choice, it was an active decision, and she ought not to back away from it. It makes her sound too much like the naive young girl who walked into that bookstore in Maine decades earlier — and if a narrative needs anything, even one by a radical naif, it needs character development.

Ted Rall is a syndicated political cartoonist, columnist, and war correspondent. His books include “The Anti-American Manifesto” (2010) and, most recently, “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back as Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan.” He will appear at BookHampton in East Hampton on Oct. 26 at 11 a.m.

Linda Coleman lives in Springs. She will give a reading at the East Hampton Library on Oct. 18 at 1 p.m.