For the Sake of the Family

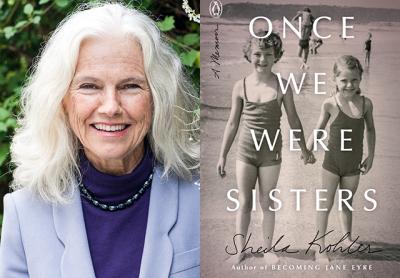

“Once We Were Sisters”

Sheila Kohler

Penguin, $16

Incandescent. Sheila Kohler’s “Once We Were Sisters” is a story of betrayals. Not a thousand pinpricks. A thousand sword thrusts. Yet how can a memoir about a sister’s death — most likely caused by her wife-beating husband, who may have been trying to engineer a car crash to kill himself as well and leave their five children orphans — be so luminous? Ms. Kohler’s patient storytelling. Analysis and reanalysis of the events. Beautiful language. Rancor under control.

The two sisters grew up on Crossways, the family estate outside apartheid Johannesburg, tended to by legions of servants. When Sheila is 7 and her sister, Maxine, is 9, the parents leave on an 18-month around-the-world tour, ostensibly a business trip. Not so terribly long after this tour their father dies.

Their mother, vacillating between distant and far-too-invasive, sends them to boarding schools as well as a few suspect “finishing schools.”

Above all, Mother sleeps. She grasps sleep greedily in her clenched fists, as though it were the most precious thing in the world. She sleeps all through the long hot afternoons in the green light of her high-ceilinged room with the shutters drawn down, one arm flung with abandon across her face, her dark curls clinging to her damp forehead.

And she drinks. She starts drinking at sundown on the glassed-in veranda, surrounded by her two sisters and younger brother, while the blue hills disappear in the dim light.

These maternal relatives will come back to play a major role after Ms. Kohler’s mother’s death.

But first more about Ms. Kohler’s years of longing and self-discovery. She loves literature. She yearns to write. Her mother’s take? “When I tell Mother I would like to be independent, to find meaningful work, she stares at me blankly and says with genuine surprise, ‘What on earth would you want to work for, dear?’ Much of her life has been a successful struggle to avoid any work.”

Within close proximity Sheila and Maxine marry. Sheila has become pregnant upon losing her virginity, although the pregnancy does not come to term. Her husband, Michael, is a handsome American scholar. They live in Paris. But when the larger family travels through Europe, Michael chooses to remain apart. “In Rapallo Michael prefers to lie on his bed and read ‘Jane Eyre.’ My mother scoffs. ‘A man does not read in the morning,’ she says. Reading is considered an idle pastime, not to be indulged in too frequently. It therefore becomes an illicit source of pleasure.”

Maxine marries Carl, an extremely well-regarded Afrikaner heart-transplant surgeon. “Mother says my sister and I have both married vultures, bloodsuckers. Mother does not mince her words.” Both young women begin bearing children. But Maxine is often beaten “black and blue.” Her children are sometimes harmed as well. This by a man who saves people’s lives, who holds human hearts in his hands in the medical theater.

Not long after, Sheila Kohler’s husband drinks a bottle of vodka and announces he’s having an affair. She turns to Nonna, her mother-in-law, for advice. “There are triangles within triangles in this complicated plot,” Ms. Kohler writes.

In my case [Nonna] counsels patience. (I am, you have to understand, paying the mortgage on her apartment in Switzerland and our entire household is mainly maintained by my money.) She tells me not to make her son feel guilty: “No one wants to feel guilty, do they dear?” she asks me.

“Indeed,” I, the guilty one, say.

“Pretend he has the measles,” she says. “Pretend to be asleep when he comes home late at night,” she says. “The family is sacred, don’t you think, darling? Do it for your girls,” she says, and advises taking a lover.

Throughout, the sisters remain close, visiting each other, often with their children, in France, Italy, skiing, living: “My sister and I are always flying long distances back and forth to meet in beautiful places.” But there is one day in Rome when the two sisters are to meet at the Hotel Hassler on the Spanish Steps. Maxine is late. Sheila grows increasingly concerned. She thinks about the moment when her brother-in-law, Carl, has told her of a time when Maxine was extremely ill: “. . . he imagined he would be accused of killing her.”

“ ‘Why on earth would they accuse you?’ I asked innocently at the time, though my words would come back to me with an ominous ring. As I write of them today, hindsight casts its dark wing and colors them. For who else but someone with murder in his heart would have that troubling thought? Was this something Carl had planned to do for a long time or at least considered? Was it a constant possibility in his mind? A way out of his unhappiness?”

In the extraordinary chapter just before these thoughts, Ms. Kohler writes of the time when Carl called the black female servants into the bedroom to help the “ ‘master,’ and they are forced to participate in a particularly South African form of wife-beating, holding my struggling sister down on the bed, while he beats her.” Maxine was 39 at the time their car crashed into a lamppost on a deserted road.

Ms. Kohler delivers so many of these horrors to us ever so gently. She writes about her three great-aunts, who were spinsters. Why? Because their father’s will stipulated that if any of the them married, all their diamond-mine money would be taken away from all three of them to be distributed to their cousins. Those cousins? They kept sending suitors over, hoping to appropriate their fortune.

Ms. Kohler’s own mother? She left all of her money to her ne’er-do-well side of the family. Not a dime for Ms. Kohler, her only direct descendant.

Even today Ms. Kohler keeps a photo of Maxine in her presentation dress for the queen on the wall of her own bedroom. People mistake the young woman in the image for Ms. Kohler, “which makes my heart tilt with sorrow.”

Ms. Kohler writes about how hard she has looked for the truths of her life and of her sister’s, how she has used and sometimes misused the facts of their lives and the lives of people around them in her fiction — she has written 10 novels. This memoir comes across as remarkably, heartbreakingly true. This writer is not settling scores here. She is coming to grips with the overarching mysteries and extraordinary pains of her life.

Yet even that Sisyphean task brings more heartbreak: Ms. Kohler dedicates this memoir to her sister’s five children. Who lost their mother at a very young age.

Laura Wells is a regular book reviewer for The Star. She lives in Sag Harbor.

Sheila Kohler lives part time in Amagansett.