The Soulful Iguana

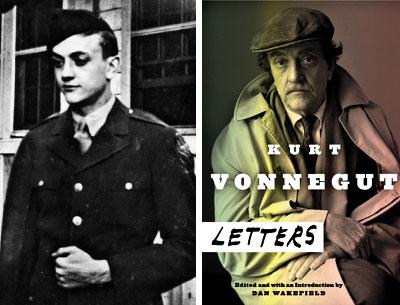

“Kurt Vonnegut: Letters”

Edited by Dan Wakefield

Delacorte, $35

Whackadoodle. That’s a word that was frequently muttered after meetings with Kurt Vonnegut. In this collection, “Kurt Vonnegut: Letters,” beautifully and lovingly edited by his friend Dan Wakefield, we see the whackadoodle guy plenty. And forgive me for what may sound trite, but underneath that crusty, self-described iguana exterior, he was a loving cynic. Who also proves himself to be a cynical lover, as well as a wise, irascible man who was struggling every moment to make sense of this nonsensical life. The writer of these hundreds of letters over a 60-year period displays his tormented soul, his voice by turns hilarious, angry, winsome, charming, cruel. And always thoughtful.

But let’s start at the beginning. Vonnegut, born in 1922, was of perfect age for World War II. The volume starts with the horrific shock — the bombing of Dresden — that we will see in “Slaughterhouse-Five.” As a private just released as a prisoner of war, he wrote to his family on May 29, 1945:

Dear people:

I’m told that you were probably never informed that I was anything other than “missing in action.” Chances are that you also failed to receive any of the letters I wrote from Germany. . . .

I’ve been a prisoner of war since December 19th, 1944. . . . Well, the supermen marched us, without food, water or sleep to Limberg, a distance of about sixty miles, I think, where we were loaded and locked up, sixty men to each small, unventilated, unheated box car. There were no sanitary accommodations — the floors were covered with fresh cow dung. There wasn’t room for all of us to lie down. Half slept while the other half stood. . . . They killed about one-hundred-and-fifty of us. We got a little water Christmas Day. . . . We were released from the box cars on New Year’s Day. The Germans herded us through scalding delousing showers. Many men died from shock in the showers after ten days of starvation, thirst and exposure. But I didn’t.

Vonnegut recounts beatings, fellow P.O.W.s shot dead for stealing food.

“On about February 14th the Americans came over, followed by the R.A.F. Their combined labors killed 250,000 people in twenty-four hours and destroyed all of Dresden — possibly the world’s most beautiful city. But not me.”

Vonnegut describes carrying corpses from shelters. “Civilians cursed us and threw rocks as we carried bodies to huge funeral pyres in the city.”

At the end of the war Vonnegut and the other P.O.W.s walked to the Czech border, where the guards fled. “On that happy day the Russians were intent on mopping up isolated outlaw resistance in our sector. Their planes (P-39s) strafed and bombed us, killing fourteen, but not me.”

As Mr. Wakefield points out in his insightful introduction, “but not me” is the precursor for “so it goes” from “Slaughterhouse-Five.”

In these pages we clearly see the demons against which Vonnegut struggled: the true horrors of war, the punishing effect of his father’s mandates, the family’s diminishing fortunes, his mother’s suicide just as he was going off to war. Vonnegut has always written and spoken about the travails of the writer’s life in utterly original ways. He could also fight back against naysayers: “I have been a soreheaded occupant of a file drawer labeled ‘science fiction’ ever since, and I would like out, particularly since so many serious critics regularly mistake the drawer for a urinal.”

Yet when it came to questions regarding the arts, Vonnegut was always searching below the surface — and he was generous. His brother, Bernard, once raised the question about why paintings couldn’t be judged just by their quality without viewers having to know something about the artist. Vonnegut’s response is rather surprising, given his occasional curmudgeonly nature:

“People capable of loving some paintings or etchings or whatever can rarely do this without knowing something about the artist. Again, the situation is social rather than scientific. Any work of art is one half of a conversation between two beings, and it helps a lot to know who is talking at you. Does he or she have a reputation for seriousness, for sincerity? There are virtually no beloved or respected paintings made by persons of whom we know nothing. We can even surmise a lot about the lives of whoever did the paintings in the caves underneath Lascaux, France.”

Vonnegut frequently wrote just to needle — and perhaps he was needling himself at times. A master of the shock technique, he once told Legionnaires that he couldn’t come speak at the 77th convention in his hometown, Indianapolis, explaining: “If I could be there, my speech would be a short one. The older my father became, the dumber he became, and the same thing is happening to me. . . . I’m talking about plain old age.”

Vonnegut’s agent provocateur personality is splayed across many pages. Take, for example, this 1993 letter written from Sagaponack to Knox Burger, who published Vonnegut’s first short story in Collier’s magazine. Burger, who nurtured Vonnegut his entire career, went on to found an extremely successful literary agency.

Dear Knox

That’s something nice I’d given up hoping for, an easy and friendly letter from you. The brutality of the choice I was forced to make between you and Max is now as little remembered, thank goodness, as Shays’ Rebellion or whatever. . . .

For the sake of our darling adopted daughter (half Jewish, half Ukrainian, kind of like you, now that I think about it), Lily, now ten, Jill and I are not divorced. I am too old, anyway, for all the paperwork. Divorce has become as obsolescent as marriage. My son Mark is in the process of getting divorced, and I’ve said to him, “Why bother?”

And yet suddenly there are tender, passionate Vonnegutian outbursts. Here’s an unsolicited message to the poet Galway Kinnell.

December 22, 1997

New York City

Dear Galway Kinnell

At the age of 75, I had come to doubt that any words written in the present could make me like being alive a lot. I was mistaken. Your great poem “Why Regret?” restored my soul. Jesus! What a language! What a poet! What a world!

Cheers! —

Kurt Vonnegut

Underneath the bluster, there is a pervasive tenderness. Vonnegut once said, “I urge you to please notice when you are happy, and exclaim or murmur or think at some point, ‘If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.’ ” Indeed, in “God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater,” one character says, “. . . babies — God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.”

One of the truly charming aspects of this collection is Vonnegut’s underlying devotion to offering advice. Despite his conflicts about being a teacher and his own lackluster traipse through academia, again and again his love of teaching comes through — in addition to his love of the epistolary form. In 1965 he became writer in residence at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. All of his course assignments were delivered in the form of a letter. Here’s a snippet from his “Form of Fiction Term Paper Assignment”:

Beloved:

As for your term papers, I should like them to be both cynical and religious. I want you to adore the Universe, to be easily delighted, but to be prompt as well with impatience with those artists who offend your own deep notions of what the Universe is or should be.

He “invites” his students to read 15 short stories, then grade them from A to F. Then he directs them to “Proceed next to the hallucination that you are a minor but useful editor on a good literary magazine. . . .”

He asks students to write a report on three stories they like and three they don’t and to write a report for a “witty and world-weary superior.”

Do not do so as an academic critic, nor as a person drunk on art, nor as a barbarian in the literary market place. Do so as a sensitive person who has a few practical hunches about how stories can succeed or fail. Praise or damn as you please, but do so rather flatly, pragmatically, with cunning attention to annoying or gratifying details. Be yourself. Be unique. Be a good editor. The Universe needs more good editors, God knows.

Since there are eighty of you, and since I do not wish to go blind or kill somebody, about twenty pages from each of you should do neatly. Do not bubble. Do not spin your wheels. Use words I know.

POLONIUS

Skip 31 years. Vonnegut writes to a friend, “When I teach creative writing, I make Vincent Van Gogh the class hero, since he responded to life rather than to the marketplace, and the class motto is: ‘Whatever works works.’ ”

In 2000, Vonnegut accepted a teaching gig at Smith: “I sure need something to do,” he wrote Norman Mailer. A world-famous writer who could have done whatever he wanted whenever he wanted, he nonetheless carefully timed his life around the school calendar. Yet he was also already admitting that his own fiction wasn’t going so well. “My writing grows clumsier with each passing day,” he admits to Mailer.

The last letter collected in this volume was written in 2007, the year Vonnegut died, to Alice Fulton, a poet and Cornell faculty member who had requested Vonnegut come lecture. (Vonnegut had attended Cornell.) “Alas . . . at 84, I resemble nothing so much as an iguana, hate travel, and have nothing to say.” He muses over the fact that when he was at Cornell, he majored in chemistry “at the insistence of my father: ‘Learn a trade!’ ”

And then the poignant end to this letter to Ms. Fulton: “But God bless you for being a teacher.”

There is a fullness one feels upon finishing this important volume. An understanding of Vonnegut’s diffidence. A marveling at his brilliance and the generousness of his spirit despite, despite, despite . . .

Laura Wells is a writer and editor who lives in Sag Harbor.

Kurt Vonnegut lived in Sagaponack for many years.