Student Takeover

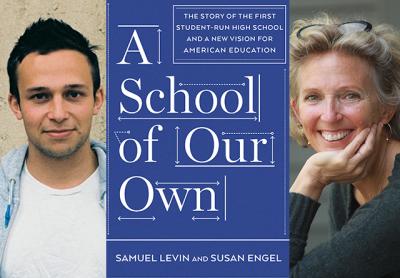

“A School of Our Own”

Samuel Levin and Susan Engel

The New Press, $25.95

Confessions of a reviewer: A book with two authors? Approach with caution. A mother-son writing duo? Possible treacle alert. A teenager who started his own school? Whoop! Whoop! Whoop! Back-patting danger.

Sigh of relief: This book? No need for alarm. Not cloying. Not self-congratulatory. Instead — thoughtful, thought-provoking, moving.

Here’s the premise, and it’s unusual. Samuel Levin was a high school junior. His before and after-school job was tending cows on a dairy farm — a job he loved. He makes clear over and again how much he loved the heifers, the milking, the smells, the early mornings, even the cow dung. One exceptional young man.

Who knew that what was happening in his high school was so incorrect? “. . . I’d sit through the first three periods of my day, mostly bored, occasionally annoyed. In the classes that were the least boring, I tried to think of ways to make them more interesting. I’d translate words to binary, think of alternative explanations for data that purported to support a theory, design math puzzles. In the most boring classes, I just thought about other things. I planned science experiments, wrote stories, or daydreamed.” This was not a disaffected young man: He revered his one-on-one math teacher, whom he termed “brilliant.”

Lunch was all right. But then there was the English class with the teacher who “seemed to not like books, or kids for that matter.” Here was a young man who was furious for good reason.

Weave in his mother’s commentary. “Weave” is the perfect verb because her commentary is seamless. Sam is Susan Engel’s third child; the other two had already graduated from college by the time he was tackling his junior year. “I was painfully aware, like other parents, of the pitfalls of adolescence. After all, there are so many ways for kids between the ages of fourteen and eighteen to screw up. It would be hard not to quake at the potential disasters that lie in wait for the teen who goes astray.”

Ms. Engel goes on to cite the work of the anthropologist Ruth Benedict, who noted “that many cultures lead their youngsters toward maturity by gradually giving them more autonomy and accountability. But our culture, she pointed out, did not. In fact, she argued, our society was notable for the disjuncture we create between childhood and adulthood. We baby them for a very long time and then fling them into a free fall toward adulthood.” And then, gulp, Ms. Engel tells us that Benedict was writing in 1934. How little has changed.

Then one day, not unlike any other, Sam made sure that so much did change. He worked intensely on creating “the Independent Project.” He figured out how to work with educators and fellow students to create a curriculum that would work for his fellow students, for himself, and for teachers. A high school that was a high school created by students, for students, about students.

His mother’s comments? “At seventeen, Sam was naive. And he was brash. From the time he decided to do this, it never seemed to occur to him that he might not get past the first stage.” She knew the pitfalls that awaited him. She knew the possibilities of success.

And success came piling on. Fellow students loved IP. They were no longer bored, angry, disillusioned. They were connected to their studies.

Mr. Levin inherited the educational reform genes from both his grandmother and mother. His grandmother Tinka Topping and Ms. Engel have been education advocates on the East End for decades, playing pivotal roles in the founding of the Hampton Day School — back in the late 1960s — as well as the Hayground School. Ms. Engel, a psychology professor at Williams, is an expert in autobiographical memory and the development of curiosity. Her previous books include “Real Kids: Creating Meaning in Everyday Life.”

A proofreader this reviewer would have hoped for: a high school English teacher (different from the one referenced above) who might have caught noun-pronoun disagreement and a few other grammatical snafus. However, it is the heart, the passion of the underlying mission that carries this book.

One of the impressive aspects of this educational experiment is the willingness of Mr. Levin and Ms. Engel to discuss shortcomings. In “Appendix: Nuts and Bolts,” the authors admit that teachers are not as widely acknowledged in the text as they were in the beginning of the work.

“We haven’t discussed teachers yet,” Ms. Engel writes, “because Sam originally envisioned one role for them and ended up contending with a very different one. The truth is, the school wasn’t able to allot the teacher hours the IP wanted. This is ironic, given that one of the faculty’s biggest fears was that teachers would become irrelevant or redundant in the IP. Part of it came down to the unions. The teachers couldn’t work with the IP without extra compensation, and the school didn’t have enough money for that. The upshot was that teachers had a surprisingly marginal role in the Independent Project, when they were intended to have a central role. . . . The teachers’ job in the Independent Project is nuanced and slippery. They have to guide without leading, help without pushing. They must use their judgment about when to step in and when to step back. They should use their passion for and mastery over their own subject to model how to work in that field.”

“A School of Our Own” is a mother-son love story. A love story regarding learning. One of the most touching love stories is one of the most unexpected: A young woman in the IP project was cutting class during IP. Problematic, right? Where was she? Sneaking out to memorize lines from “Macbeth.”

Susan Engel grew up in Sagaponack. She and Samuel Levin will speak about their book next Thursday at 5:30 p.m. at the Hayground School in Bridgehampton.

Laura Wells is a regular book reviewer for The Star. She lives in Sag Harbor.