'The Whole City Moaned'

On a normal weekday morning at 8:48, Lakshman Achuthan, whose parents, brothers, and sisters live on the South Fork, would have been just arriving at his office in the Economic Cycle Research Institute above Grand Central Station, but on Tuesday he was on the first floor of the World Trade Center's north tower in the Marriott Hotel attending a conference.

Dan Rattray was looking out the window of his West Fourth Street apartment with his infant son, Ray, when he saw an airplane flying low over the city. "It seemed like it was coming in slowly, like it was coming in for a landing," Mr. Rattray said. "Then the next minute it hit the World Trade Center."

Karen Rickenbach, a daughter of East Hampton Village Mayor Paul F. Rickenbach Jr. and his wife, Jean, who worked on the 56th floor of the north tower in Sidley, Austen, Brown and Wood's human resources department, was having morning coffee with a co-worker when she felt a major jolt to the building. Soon after, she said, she heard people yell "Evacuate!" and with her co-worker began running down the steps.

By about the 10th floor, Ms. Rickenbach said, they met firefighters headed up the steps, who gave them water and told them to then spit it out and keep their mouths closed.

So many floors below the crash, Mr. Achuthan heard what he described as "a thud" and felt the building shake. Everyone in the crowd of 150 stopped and looked around. "I thought it was an earthquake," he said. Then came another thud and the lights flickered.

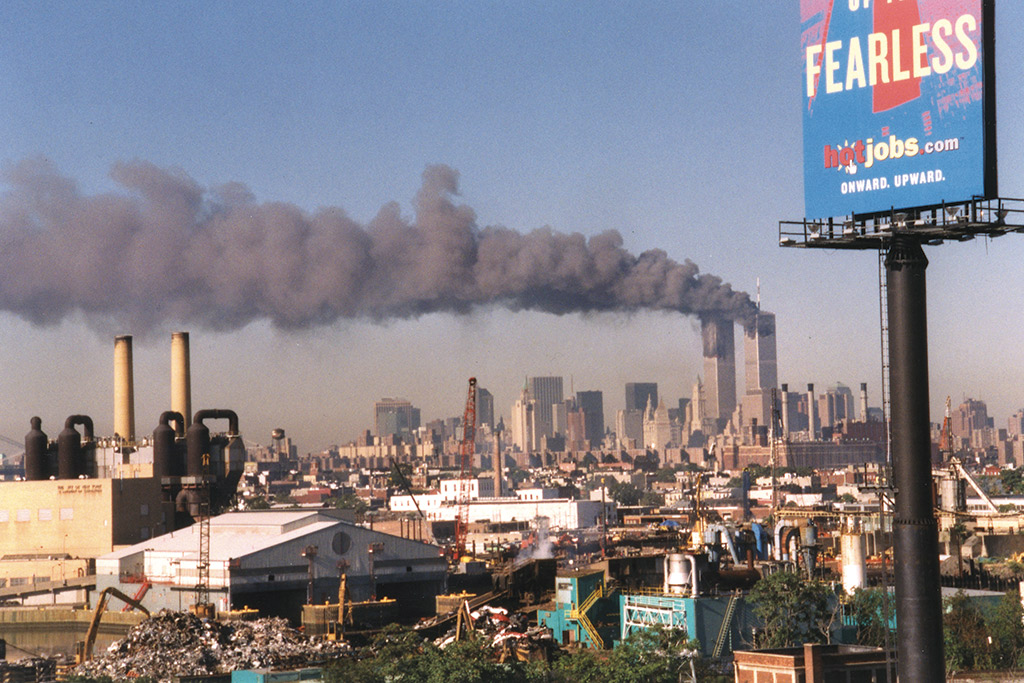

Ted Weissberg, who has a house on Beach Road in Amagansett, was cycling across the Brooklyn Bridge to his office at 195 Broadway, a block east of the World Trade Center, when he saw the smoke and flames high in the north tower. Concerned about his co-workers, he continued pedaling toward his office.

Down on the north tower's first floor "everybody started running," Mr. Achuthan said. "It wasn't mayhem, but it was fairly hysterical running." People ran into the main lobby near the elevators, but smoke was already billowing into the lobby near the elevators, so the crowd turned around and went the other way, he said. "There was a lot of glass and we were just seeing things fall onto West Street - hunks of the building." Outside in the street, cars were careening into each other.

The group from the conference continued to try different exits, their efforts to leave the building complicated by revolving doors. Finally a security guard opened a door to the bar, which led to a side exit. Again Mr. Achuthan saw debris crashing to the ground, but this time, he said, "it came in a wave and then it lightened up."

He and a small group he was with ran across the traffic and headed to the water, followed by scores more escaping from the building. Ms. Rickenbach and her co-worker were among them. Speaking to her father later in the day, she described the scene as surreal. "Daddy," she said, "I saw people go out the windows."

"It was sickening to see that," Mr. Achuthan said. Only from the outside of the building could the survivors sense the extent of the devastation.

"I was trying not to look," Mr. Achuthan said. He looked to the south, away from the twin towers, and saw the other plane approaching. "It was in perfect control. . . . For a moment, you could hope it would fly past, and then there was a massive explosion. At that point it became very clear that we were under attack," he said.

As Mr. Weissberg was locking up his bike a couple of blocks from the World Trade Center, he heard, and felt, the second explosion. "And then there was bedlam . . . people running and screaming . . . panic." He turned around and wheeled his bike back across the Brooklyn Bridge in the middle of a mass of people. Ms. Rickenbach, too, walked across the bridge and home to Park Slope.

Warren J. Mula, who comes to Amagansett in the summer, works for the Aaon Insurance brokerage on the 102nd floor of the south building, the second to be hit. He was at work at 6:15 a.m. as usual, but on this particular day he had a doctor's appointment. At 8:15 a.m. he left the building.

Aaon had 1,500 employees in its World Trade Center offices; checks are now being done to see who survived and who did not. Mr. Mula said a colleague who escaped told him that at first those in the south tower were told to stay put because of the danger of falling debris. Those who ignored the warning may have escaped with their lives.

Scouring the sky for more planes, Mr. Achuthan joined a mass exodus of people running up the West Side. He ran as far as his apartment on West Broadway between Spring and Broome Streets. From there he and his wife, whom he had called earlier, saw the first building and then the second collapse completely.

"You heard huge moans. The whole city moaned," he said.

Mr. Mula made his way across to the Hudson River, where he and 12 others got into a small boat and were ferried to Hoboken, N.J. There they had to pass through a decontamination booth and be hosed down - no exceptions, even though Mr. Mula was not covered in dust like the others.

Mayor Rickenbach, like so many others, heard of the first Trade Center blast on the radio at a little after 9 a.m. and began trying to reach his daughter by phone. The Rickenbachs were thwarted, as were so many others, by busy circuits, and then tried to locate their daughter through the Red Cross.

"It was almost 1 p.m. before Karen called" to say she was all right and tell her story, he said yesterday. "I was very happy to be able to talk to her today."

Others were not so fortunate. Many have yet to hear from relatives and friends who worked in the twin towers. Still more wait to hear from their loved ones in the police and fire departments who were called upon to help rescue the victims of the attacks, and may themselves have perished in the process.

With Reporting by David E. Rattray, Susan Rosenbaum, and Sheridan Sansegundo