Yet Another White Meat

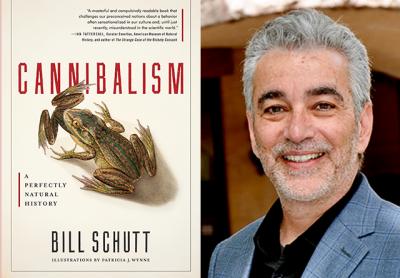

“Cannibalism”

Bill Schutt

Algonquin Books, $26.95

It’s not necessarily a subject one would expect in a book aimed at a general readership. Those who overcome their surprise, however, and pick up Bill Schutt’s recently published volume, “Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History,” will be rewarded with a well-organized, thorough, and highly readable study of a phenomenon few of us pause to think about. This is a book you can sink your teeth into. (I promise, I’ll stop.)

If there is an implicit subtext to Mr. Schutt’s work, it is to question the origin and the reasonableness of the taboo against consuming other humans. A biology professor at L.I.U. Post and a research associate in residence at the American Museum of Natural History whose previous work was “Dark Banquet: Blood and the Curious Lives of Blood-Feeding Creatures,” he is a qualified guide for the journey on which he leads us.

That journey begins, very logically, in the realm of nature. How common is it for creatures to consume their own kind? And for what reasons do they do so? Mr. Schutt is intent on pointing out that cannibalism is hardly an anomaly in the natural world, although he is eager to dispel certain myths concerning some of the species in which it is presumed to be common.

He provides a wide variety of examples, including tadpoles, certain snails, chimpanzees, sand tiger sharks, and polar bears. Not surprisingly, the less-well-known examples make for some of the most interesting reading. The descriptions of the elaborate mating practices of the Australian redback spider are fascinating. The excellent nature illustrations by Patricia J. Wynne deserve credit for adding interest as well as understanding.

While establishing that cannibalism is well documented in the natural world, Mr. Schutt helps us place the phenomenon in proper perspective as he builds toward the consideration of cannibalism among humans. “Currently, only 75 species of mammals (out of roughly 5,700) are reported to practice some form of cannibalism.” He adds that the “overall low occurrence of cannibalism in mammals is likely related to relatively low numbers of offspring coupled with a high degree of parental care (compared to non-mammals).”

What can we conclude about the prevalence in nature of members of various species consuming their own? Cannibalism “occurs across the entire animal kingdom, albeit more frequently in some groups than in others. When the behavior does happen, it happens for reasons that make perfect sense from an evolutionary standpoint: reducing competition, as a component of sexual behavior, or an aspect of parental care.”

Which brings us to the human realm, where Mr. Schutt writes as well about history, anthropology, and psychology as he does about science. When it comes to human cannibalism, we tend to think about overcrowding and food shortages. “The unfortunates involved in shipwrecks, strandings, and sieges have also resorted to cannibalism, and by doing so they exhibited biologically and behaviorally predictable responses to specific forms of extreme stress. Although conditions may have been unnatural, the actions that resulted were not.”

In addition to consideration of the siege of Leningrad during World War II, Mr. Schutt gives us a highly detailed chapter about what befell the Donner Party as they attempted to make their way from Independence, Mo., to California by stagecoach in 1846 and 1847. It’s fascinating, gruesome, and deeply affecting. Research into the events surrounding the Donner Party is ongoing, and Mr. Schutt gives us a synopsis of it, including the confusion that ensued in 2010, when some public-relations hacks at Appalachian State University issued a premature report on work by A.S.U. researchers that gave the impression that there may have been no human cannibalism among the Donner folks. Spoiler alert: Not true!

The author disabuses us of the notion that human cannibalism is universally viewed as aberrant behavior. He catalogs instances, over a wide swath of history, of its being culturally approved — including among certain Chinese people until well into the 20th century.

On the other side of coin, Mr. Schutt also pays ample attention to the sources of the widespread cannibalism taboo. He examines Freud, the Brothers Grimm (many of whose folk-tales-turned-fairy-tales are posited as cautionary tales for badly behaved children), and the Judeo-Christian tradition, which holds that dead bodies must be preserved intact so that body and soul can be reunited at some idealized point in the future.

As an author, Mr. Schutt evidences a number of admirable qualities. His breezy style helps make palatable (oops!) a difficult subject. Of the female redback spider, for example, which consumes parts of her partner as they mate, he writes, “While the benefits of a risk-free meal for the redback mom-to-be are fairly obvious, one has to wonder what the hell is in it for the male?” (The answer, by the way: “The puzzled scientists determined that females that had recently eaten their mates were less receptive to the approach of subsequent suitors. Cannibalized males also copulated longer and fathered more offspring than non-cannibalized males.”) Isn’t nature grand!

Elsewhere, the chapter on George Donner and his fellow travelers is titled “The Worst Party Ever.”

An experienced scholar, Mr. Schutt is not lazy when it comes to thoroughly reviewing extant research on his subject or interviewing other researchers. Moreover, he was willing to travel widely in pursuit of material. Among other places, we find him wading knee-deep in a pond in Arizona, examining salamanders, tramping around Alder Creek, Calif., in the Sierra Nevada foothills, in 105-degree heat, accompanying a border collie specially trained to detect buried human remains, even 170 years after the Donner Party set up camp there, and dining on sautéed human placenta in Dallas with a mother of 10 who had saved an extra one for him. (“Within seconds, the kitchen filled with an aroma that reminded me of beef.”) That particular chapter, incidentally, bears the title “Placenta Helper.”

Looking to the future, Mr. Schutt wonders whether climate change could create the kinds of crowding or shortages that would have an impact on various species, including humans.

Ultimately, the question becomes, does shedding light and fact and understanding on the matter diminish the taboo that has so long and widely shadowed cannibalism? That is probably for each reader to answer individually. As for me, I will only say that I hope the editors of The Star don’t place this review in too close proximity to the paper’s “News for Foodies” column.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.

Bill Schutt, who lives in Hampton Bays, will read from “Cannibalism” at Southampton Books on April 1 at 6 p.m.