Ralph Gibson was 16 when he was banished from his father’s Los Angeles house and dropped out of high school. He enlisted in the Navy a year later, qualified for training as a photographer’s mate, and then flunked out of photography school. “I felt I had failed my family. I was 17 1/2 years old and had very low self-esteem,” he said recently at his house in Sag Harbor.

He was readmitted to photography school and succeeded the second time. Soon after, having been assigned as a ship’s photographer’s mate on the U.S.S. Tanner, he found himself on night watch while crossing the Atlantic during a raging gale. As he wrote in “Self Exposure,” his autobiography, “In utter misery, I raised my head to the heavens and shouted as loud as I could, ‘I’m going to be a photographer!’ From that instant on, I knew my destiny.”

Sixty-two years later, his photography earned him France’s highest order of merit, Knight of the Order of the Legion of Honor, which was presented to him by that country’s Minister of Culture. In the interim he published more than 40 monographs, received countless awards, including several honorary doctorates, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and induction into the International Photography Hall of Fame in St. Louis, and saw his photographs enter more than 200 public collections.

Mr. Gibson is one of seven artists named by the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill as a juror for its “Artists Choose Artists” exhibition, which opened on Sunday. His work will be shown along with that of the two photographers he selected, Tria Giovan, who lives in Sag Harbor and New York City, and Thomas Hoepker, who divides his time between Southampton and New York.

Mr. Gibson spent his three years in the Navy studying photography and classical guitar. Through magazines such as Popular Photography, Modern Photography, and Camera 35, he was aware of important photographers such as Atget, Cartier-Bresson, and Walker Evans. Being based in New York City, he was drawn not only to photography but also to the haunts of the action painters, Beat poets, and jazz musicians.

After his discharge in 1960 he attended the San Francisco Art Institute and worked as an assistant to Dorothea Lange. “She was old and dying, but on her way out she handed me the key to my career. After I showed her my student work, she said ‘I see your problem. You have no point of departure.’ The idea was that if you’re just wandering around with a camera, you won’t get anything. But if you go out looking for a guy picking his nose, you might find a guy scratching his ear.”

By way of demonstration, Mr. Gibson pointed his right index finger toward the ceiling and asked a visitor what he saw. “Your mind’s eye selected my finger,” he said. “What about the rest of the room, the outside, the door, the window? That’s what happens in most photographs. The guy is picking his nose. Meanwhile the dog is peeing and the house is on fire.”

Another important moment for Mr. Gibson came in the mid-1960s, when, at the age of 27, he was working for Magnum. At the time, he was walking across the street in Manhattan and saw a beauty parlor on fire. “I couldn’t help but photograph it. And as I photographed it, this catharsis of tears flowed out of me.” His mother, who had owned a beauty parlor, died in an apartment fire.

“And in that instant, I knew I wasn’t going to be a commercial photographer. I wasn’t going to sell my soul. If I stayed true to the medium, I could find my soul. I started working in a much more surrealistic vein. And I dropped out of Magnum because I didn’t want to make ephemera. I wanted to make pictures that would last. Longevity is the hardest thing to build into a photograph.”

Mr. Gibson first used a Leica camera in 1961. “I’m still finding moves with my Leica, I’m still attempting to refine my camera handling.” He worked for 40 years exclusively with the 50 mm lens. “I tell people if you spend a couple of years working with the 50, you can apply what you’ve learned to all the other lenses. So my current thought is, learn how your lens sees, and your lens will learn how you see.”

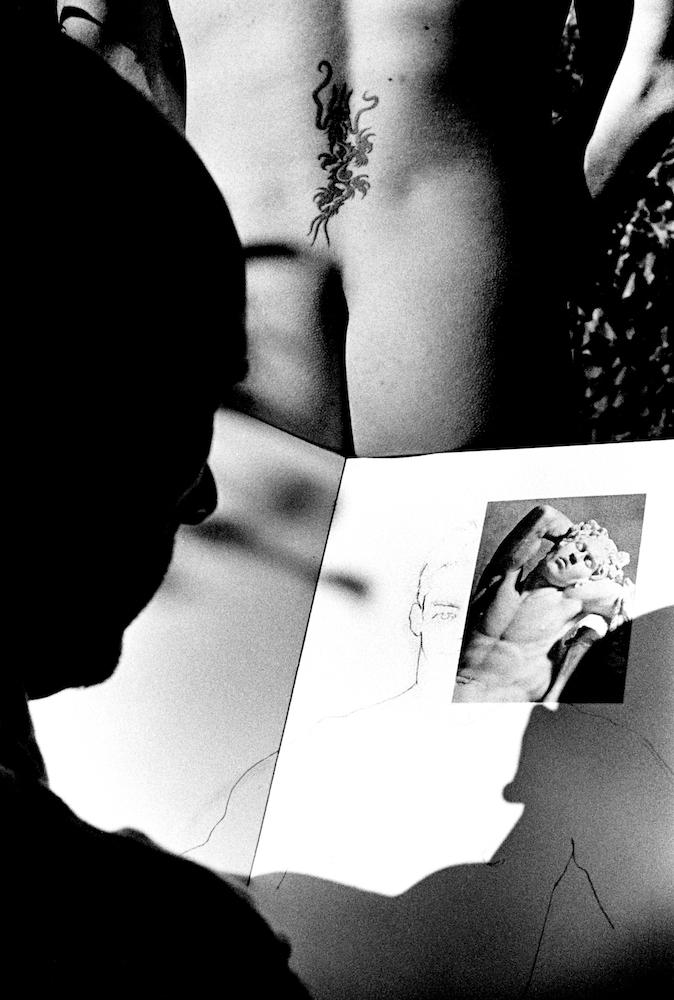

His signature style includes intense sun, dark shadows, deep blacks, focus on details or fragments, precise vantage points and framing, strong diagonals, stark contrasts, and an overwhelming preference for vertical images.

“In Western society and now the world at large, all narrative was set in the form of the horizontal. That’s if you look with two eyes. If you look with one eye you start to get a vertical hit. I use the vertical format as a form of dramatization, intensity, emphasis. And of course it fits on the page, and I’m still queer for the book.”

Mr. Gibson published his first book, “The Somnambulist,” in 1970, under the banner of Lustrum Press, his own imprint. “Deja-Vu” (1973) and “Days at Sea” (1974) followed. Britt Salvesen, who organized the exhibition “Ralph Gibson and Lustrum Press” at the Center for Creative Photography in 2007, said Lustrum Press “had an immediate impact on the photography scene with its striking and often provocative publications.” In addition to his own work, Mr. Gibson published Larry Clark’s “Tulsa” and Mary Ellen Mark’s “Passport,” among others.

When printing “The Somnambulist,” he added additional ink and started building up his blacks. “Then I started walking on the sunny side of the street and exposing for the highlights and letting the shadows drop out, getting my blacks instead of having to print them in the darkroom or ink them on the press. I started underexposing my shadows, so my big blacks are a form of subtraction.”

Five years ago Leica sent him a digital camera to try out. He took it outside and pointed it at a manhole cover just as a bicycle drove by and cast shadows across the pavement. “I haven’t loaded a camera since the day I took that picture,” he said. “I’ve got 60 something years in the darkroom and I hope I have 60 years with digital. The digital language reflects my syntax.”

It makes sense, for ultimately his photographs depend less on the device than on his vision. “I like to think the subject of my photographs is how I look at something. I’m not going to rely on a great event. If there’s any kind of event in my pictures, I’m determined to transcend it. I’m more interested in the formal properties of what I see.”

He noted that he has been aware of Ms. Giovan’s photography for many years. “I was always impressed with her because she’s a straight-ahead, rock-solid photographer. In whatever small way I could, I was happy to add to her recognition. That’s why I chose her.”

“Thomas [Hoepker] is a hugely successful 83-year-old photographer who as a photojournalist has impacted our

perceptions of the world. I thought it would be nice to have his work seen in the museum context, as opposed to the ephemera of media.”

The museum’s curators selected

five images from Ms. Giovan’s “Cuba Archive” that were taken in 1993. During a six-year period in the 1990s she made 11 trips to Cuba and produced over 25,000 images. She grew up in the United States Virgin Islands and felt that perhaps Cuba had had a reprieve from the general homogenization of the Caribbean. “I was also intrigued because you weren’t supposed to go,” she said.

Mr. Hoepker will be represented by five images from his most recent book, “Strange Encounters,” which includes some of his favorite images from his long career. The photographs in the show were all taken in cultural situations, among them the Parrish Art Museum, the Margulies Collection, the High Line, and the Whitney Museum. He enjoys shooting in museums in part because he is likely to come upon unexpected and sometimes amusing images.

Mr. Gibson first came to the East End in 1968 with the photographer Robert Frank. Before moving into his current home in Sag Harbor he rented a house on North Haven for many years. “I had noticed that the South of France was one of the force fields on the planet where a lot of artists lived to a very old age. I think the East End has a little shot of that, too.”

He’s not one to rest on his laurels, even at 80. He missed the “Artists Choose Artists” opening because he was on his third trip this year to Israel, shooting photographs for a book titled “Sacred Land.” “I’m a lapsed Catholic, I’m not religious, but I walked around with a lump in my throat. It is beyond rich.”