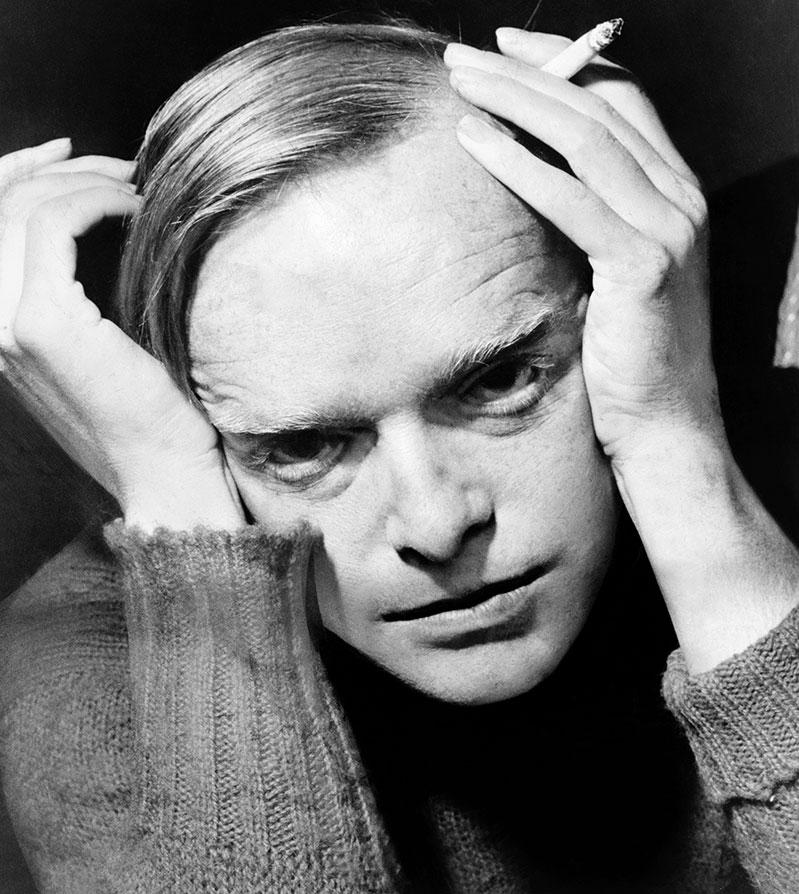

After making documentaries about Diana Vreeland, Peggy Guggenheim, and Cecil Beaton, Lisa Immordino Vreeland turned her attention to Truman Capote. "I had done all my research on Capote, and then I got wind that this other film was going to come out," she said during a recent conversation. That film was "The Capote Tapes," which eventually played at the 2019 Hamptons International Film Festival.

Even though she knew her film would be different because it would focus primarily on Capote's writing, one of her producers, Mark Lee, suggested she "throw Tennessee Williams into the mix. And I was like, wow, that's really smart." The result is "Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation," which will have its East Coast premiere as part of this year's festival. It will be available for virtual streaming tomorrow through Wednesday.

The film is a portrait of two commanding figures and their complex and sometimes contentious friendship, told through their own words and a treasure trove of archival footage, film clips, photographs, and original manuscripts.

Ms. Immordino Vreeland read all of their books and plays first, before turning to their archives. "You're always trying to find original material to use in the film. My instinct is always to go to the original words. For the viewers, it gives an immediate intimacy."

In addition to recorded interviews with Capote and Williams, two actors, Jim Parsons and Zachary Quinto, read extensively from their writings. Both capture not only their Southern accents but also the tenor of their voices. The result leaves the viewer feeling he or she has spent 90 minutes in the company of two captivating personalities.

"They both really had the same kind of life, and the same motivating factors. Both at a young age wanted to be writers, both came from the Deep South, and both came from broken families. There was all of a sudden this story that needed to be told, but in an intimate and unconventional way. I never wanted to do a biopic."

"It was a decision made ahead of time that their words would carry the entire story," she said. "Even when I just wanted to do Truman, I knew that I didn't want to have any talking heads." The only heads that talk, except for a few questions from David Frost and Dick Cavett, are Capote and Williams, and the film is full of observations that are acute, revealing, and often witty.

Capote, for example, could go from "I invented myself, and then I invented a world to fit me" to the revelation that writing "In Cold Blood" "scraped me right down to the marrow of my bones."

Williams says of writing that "the struggle for me is creation. Luxury is the wolf at the door, and its fangs are the vanities and the conceits germinated by success." He is especially candid, admitting that "my professional decline began after 'Night of the Iguana.' As a matter of fact, I never got a good review after 1961. I was broken as much by repeated failures in the theater" he said, as by the death from lung cancer of his companion of 14 years, Frank Merlo.

Both writers discuss their homosexuality. Capote's mother took him to a doctor for male hormone shots. "In effect, she was saying, I think you're a homosexual, you little monster." Williams said that while he didn't think he had effeminate mannerisms, "Somewhere deep in my nerves, there was imprisoned a very young girl."

The filmmaker said she "knew that they were friends, but I discovered that there were distinct parallels in their lives that were really interesting. I also learned that they were writing about each other to their friends."

Between 1940 and 1960, both men traveled abroad extensively, occasionally crossing paths. Both, for example, visited Paul and Jane Bowles in Tangier, but at different times. "You could see photographs in Paul Bowles's archive of Truman and Tennessee there. I love seeing those moments in history collide."

"The film is really about the inner workings of these men. And their weaknesses, their passions, their creative processes, and how difficult it is to be creative and to maintain it." Both writers speak frankly about addiction and depression.

"Truman & Tennessee" also includes clips from many of the films made from Williams's plays, among them "A Streetcar Named Desire" ("I feel I am both Stanley and Blanche," says the playwright), "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof," and "Sweet Bird of Youth." Williams admitted he was almost always disappointed by the film adaptations of his plays.

One striking thing about the film is its visual richness. "A documentary doesn't have to look sleepy," Ms. Immordino Vreeland declared. "It should look cinematic, gorgeous." She found a bounty of photographs of Capote taken at his Brooklyn Heights home by David Attie, a prominent photographer and protege of the influential art director Alexey Brodovitch. Attie's son, she said, gave her access to "a wall full of slides, which had never been seen." She also worked with the Avedon Foundation and the Penn Foundation.

"I think there's a process of filmmaking that is academic, which I'm attracted to. It's basically going back to university at a different age in life. Making documentaries the way I make them, I'm just learning so much about things I never knew before."

The filmmaker and her husband, Alexander Vreeland, divide their time between New York and Bridgehampton. She is in the early stages of researching her next documentary, which will be about Gertrude Stein.