Douglas Thompson died on Nov. 8 at the age of 76 after a yearlong illness. He and Phillip Smith began working together in 1975. Their firm, Smith and Thompson Architects, has completed more than 100 projects. A memorial for Mr. Thompson was held on Dec. 5 at the General Theological Seminary’s Chapel of the Good Shepherd in New York, followed by a reception at the architects’ studio in Chelsea.

—

I first met Doug Thompson and Phillip Smith in the role of curator and architecture critic, but soon after that, almost instantly, we became good friends. Doug was one of the warmest, most interesting men I have ever known, and I’ve cherished his friendship over the past 30 years in a creative and collaborative engagement that almost always brought some tangible result, pushing my own perception of space to the next level of understanding.

It’s impossible to separate the man from his passionate embrace of architecture, art, and nature. It’s also impossible to imagine Doug without Phil and vice versa. They met at Columbia in 1966 and were married in 2008.

Something I wrote 10 years ago still stands: “In an age of hyper speed and information overload, the work of Doug Thompson and Phil Smith stands out as an oasis of calm. Their buildings are reflective places outside the normal pace of modern urban stress. They work in a gradual (sometimes glacial) hands-on manner in contrast to the current design practice of multitasking and global branding. . . .”

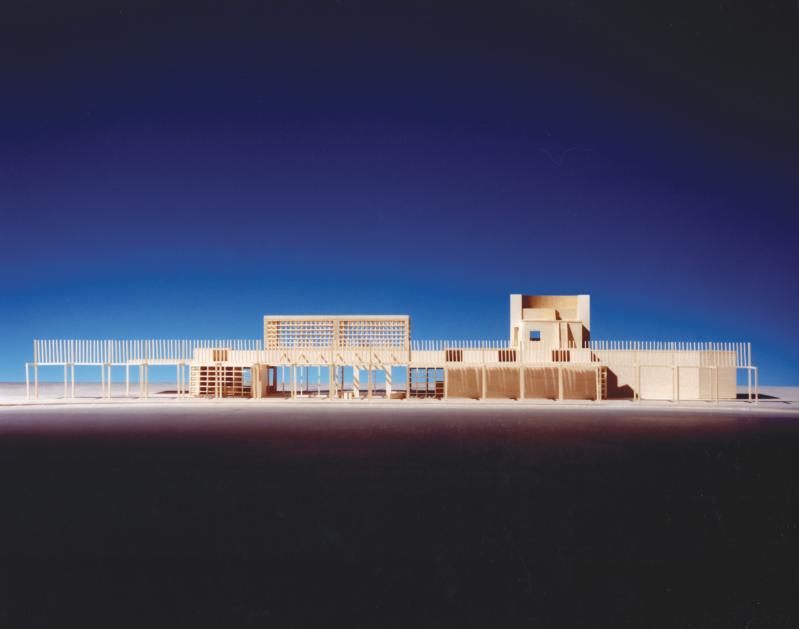

I included one of their houses in an exhibition, and they submitted plans to a design competition I organized for a new airport terminal in East Hampton. We got more than a hundred entries from around the world, and Doug and Phil won with an elegantly simple and functional plan, inspired by dune fencing and Le Corbusier’s concept of a “Naked Airport”: a horizontal pavilion with a long trellis planted with wisteria.

We bonded throughout the sometimes agonizing process of review and public reaction, and through the difficulty and humiliation of that ordeal, Doug and Phil were always the consummate gentlemen, never losing their cool, fulfilling every request with grace and courtesy no matter how unreasonable the demand.

A public referendum finally killed the project, and I remember the day when we learned the bad news — that their exquisitely beautiful airport terminal would not be getting built — we were all rattled and plotting revenge, at least I was, but Doug remained calm and poured me a large glass of whiskey and then another and we all mourned together in a much more civilized manner.

When I went to back my car out of their all-too-narrow driveway, I ripped a great gash in their vintage Mercedes-Benz. Never has anyone been more gracious and forgiving under duress than Doug on that day in 1989 when he came down, inspected the damage, and said, “Don’t even worry about it,” with a gentle smile on his face. That’s how he was.

About 10 years later they started to slow-build their “Island of Calm,” a work-live studio complex on a 54-by-40-foot corner lot at 23rd Street with Corten steel facades and a parabolic cutout to accommodate the single branch of a tree that grew on 10th Avenue.

I published a feature about it in The New York Times, “Making Manhattan an Island of Calm,” and to quote from that piece, “Their studio on 23rd Street has risen slowly on a corner lot, a tortoise among hares, while the rest of the neighborhood explodes around it, morphing from a rundown manufacturing zone into a high-speed culture zone.”

None of us had any idea just how prescient they were when they bought that corner lot and started to build, well in advance of the High Line phenomenon that opened in 2009 just a block to the west of their studio building.

Doug and Phil had a vision, but they were patient visionaries, never in a rush, possessing a kind of do-it-yourself Zen persistence, building a mixed-use structure with art galleries, their own design studio, and a small sleeping loft above, all of it terraced and set back like a pueblo village.

The thought of real estate speculation never crossed their minds. They just wanted to make a beautiful place. As Doug said, “We have this thing about vacant lots. . . . It’s the blank piece of paper, the empty canvas. We always had a dream to claim a corner of space and build ourselves a decompression chamber. . . .” And that’s what it turned out to be: a peaceful decompression chamber in the heart of a noisy, frenetic city.

As in all of their work, they drew from a diverse mix of influences gathered during their travels: Doshi’s studio in India, Maki’s conference center in Tokyo, the gardens of Kyoto, an ancient house in Cairo with multiple terraces, and then there was Noguchi’s place in Long Island City, which served as a constant touchstone.

The building continued to grow in gradual stages, as a work in progress, open ended, unfolding. “At one point we thought about just living like gypsies on the site,” said Doug, “parking a trailer and building a swimming pool. Then we could drive away whenever we felt restless.” That was pure Doug Thompson, the poet of space Peter Pan-ing away from the stranglehold of corporate architecture — do nothing, or almost nothing. That was just the kind of architectural thinking I was looking for and perhaps the most radical approach of all — park a trailer, walk away whenever the spirit moves you.

About six years later, my wife, Barbara, and I were planning to renovate and enlarge an 18th-century farmhouse in eastern Pennsylvania. We needed a special country space for our expanded family — four kids and a dog — by opening the house to the woods and three streams that converged below. It was a joyous collaboration from start to finish.

We had the mortgage and a decent builder on standby. All we needed was a set of plans. Doug and Phil came back with so much more: complete drawings and a beautiful model that was perfect for the site. It featured a spacious, flat-roofed addition clad in horizontal siding stained black in contrast to the white clapboard and pitched roofs of the original farmhouse, like salt and pepper, the new merging seamlessly with the old, stepping down the hill in different levels.

It was modern but pastoral, turning at an angle to the sloping field, the old apple orchard, and the converging streams with floor-to-ceiling glass, white oak floors, a floating staircase made from aluminum I-beams, a studio space below, two offices for our publishing company, four bedrooms, and a huge walk-in fireplace.

Five years after that, Barbara and I found ourselves in yet another Smith and Thompson collaboration. This time, a monograph about their work. Doug and Phil provided the images and ideas. Barbara designed the layout, while I wrote the text. It was also the first book Barbara and I published under our new Gordon de Vries imprint, and we were very proud of the end result.

In the beginning, I wanted to call the book “Slow Architecture.” I thought it was clever and of the moment, like the slow food movement. But Doug felt the title made it sound as if they might be somewhat “slow” themselves, dim, not entirely tuned in. We changed it to “Qualities of Duration,” and that made sense because all of their works, as well as their temperaments, were all about the perception of time, duration, restraint, natural gradations, juxtapositions of old and new, layering, patience, quietude, and, yes, slowness.

An added joy was discovering projects that I hadn’t known before. These included a series of urban lofts, a museum of Tibetan art, a number of beach houses, and their own house in East Hampton. Starting as a potato barn, their house slowly accreted over the years into a laterally stretched collage of parts, with a pool house out back in the form of a garden folly with sod roof. As one reviewer noted when the book was published in 2012: “Smith and Thompson have clearly dedicated their lives to the poetry of architecture rather than its calculus.”

Barbara and I continue to live in the house that Doug and Phil designed. Not too far from the city, it is equally in tune with the surrounding wilderness of hawks and eagles, many a black bear and great blue heron and coyote, and even the occasional wildcat sniffing around the compost heap. In his own numinous way, Doug is still around us every day, as a presence in the living spaces that he shaped for us and the afternoon shadows beneath the trees and the river-flecked light that fills those same spaces, and in the air itself. In that way, we feel lucky that he is with us still.

Alastair Gordon, a critic, lecturer, filmmaker, and curator, is the author of several acclaimed books on architecture. In addition to The Star and The Times, he has written for The Wall Street Journal and Architectural Digest. Mr. Gordon gave a version of these remarks as a eulogy for Douglas Thompson at his memorial service.