It's impossible to discuss the art and life of Dorothy Ruddick without mentioning the word rigor.

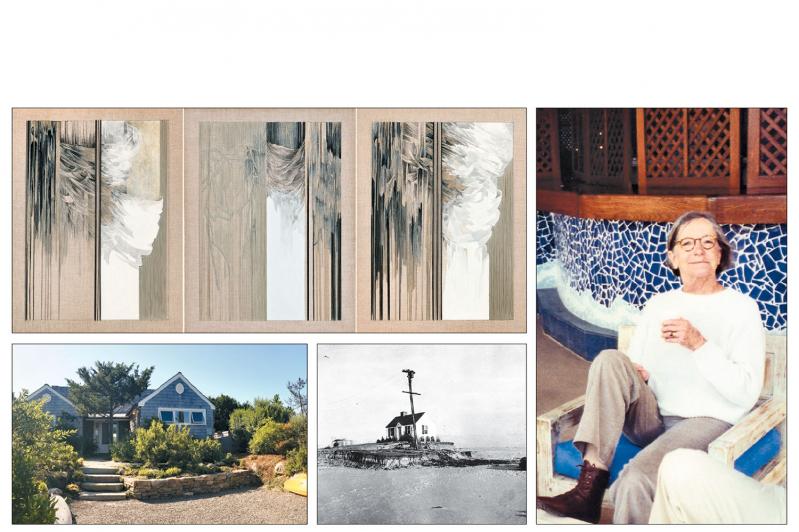

It is there in reviews of her art, in the recounting of her education at Radcliffe and Black Mountain College, her early work as a lead designer at Knoll, and in her daughters' descriptions of her approach to her art, cooking, and family life in the city and Amagansett in the summers from the 1960s to her death in 2010.

In separate recent conversations, her daughters, Abby, Lisa, and Margie Ruddick, all deemed her "an artist's artist" and mentioned their mother's endless curiosity, intelligence, discipline, and innovation and adeptness with all kinds of materials.

Working out of a large bedroom she made into a studio in their Fifth Avenue apartment and a small attic space in their house on Marine Boulevard, she would manage to eke out eight-hour workdays from the hours and minutes that her children were at school, playing at the beach in the summer, or asleep.

She was a gifted violinist, but gave it up to study art. Using the bibles of the time, "Joy of Cooking" and Julia Child's "Mastering the Art of French Cooking," she would produce elaborate dinner parties for her husband, Bruce Ruddick, and their friends. For more casual affairs at the beach, Margie recalled "living off the land out at Napeague. We would take skillets, butter, and garlic and then cook whatever we caught to make dinner."

She added that the beach parties her parents threw with many of the artists and writers who summered in the area were the kind of raucous bacchanalias that community made famous in the 1960s and '70s. This was the side of Ruddick that let go and had fun.

In the mid-1960s one of her exploding cloud drawings used as an exhibition invitation for the Graham Gallery "was pirated from the printer," Abby said, and sold as a poster in a Greenwich Village head shop. Instead of being angry, "she thought it was hysterical."

Recalling her humor and talent for deflating pretension, in his eulogy her friend Kevin Scott said she "could bring her dinner guests together in an hour of such happy communion that suddenly life, with all its letdowns, was splendid and you wouldn't trade that moment on her couch for a season ticket to the Met."

Still, he noted, "It took discipline to be Dorothy, though she usually managed to disguise it." As polite society traditions receded in the era of email and the internet, "Dorothy continued to do things the old-fashioned way. By hand. On time. In person."

At the beach, her daughters remember her guiding their friends in creative projects, and then continuing the impromptu art camp tradition with their children. "She had endless creative enterprises for us and the kids in the neighborhood," Abby recalled. "If you wanted to learn embroidery or how to draw in perspective, or do any art project, our house was the place." Adults, too, availed themselves of her expertise and joy in teaching.

Back in the city, she was showing regularly, and her work began entering the collections of significant museums.

The oft-cited rigor makes her work powerful, timeless, and unique. The 13 works on view at the Drawing Room gallery in East Hampton highlight a key stage of development in her career but are a small preview of significant museum shows to come. Her artwork stands on the precipice of rediscovery and the attention of new generations.

In a talk she gave at the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1993, Ruddick said she thought of herself as a painter, putting quote marks around the word "to emphasize, in advance, a later temporary concern with labels 'art' and 'craft.' " Prior to adopting embroidery in the mid-'70s, "crow-quill pen juxtaposed with sweeping washes on paper were my vehicle."

That changed during Watergate, when she revisited the craft she had learned as a child as she watched the congressional hearings on television. "I began to do embroidery to entertain myself. What happened soon became an obsession, and I stopped painting."

She found a distinctive richness in the expression available in thread. By enlarging a stitch, she created a shadow. She could use thread to capture raised surfaces, create positive and negative space, and explore scale in a way she could not in painting.

She started with much color and intricate "more is more" compositions, one early one looking not unlike a Marsden Hartley "German Soldier" painting. Another early example begins to contrast color and its absence while still embellishing the round surface with a rich variety of stitches. Although a breakthrough, it harks back to the more decorative "pigeonhole . . . neatly labeled 'for guest towels, tablecloths, and polite ladies' " she had placed needlework in up to this point.

The works at the Drawing Room continue to explore her new medium's potential using some of the strategies she mentioned, capturing raised surfaces, drawing in thread. Gradually her mature style emerges -- a blend of Bauhaus minimalism and craft with the Baroque, a combination startling in its beauty, restrained drama, and finesse.

Her daughter Lisa, a retired English professor, said she sometimes used one of her mother's works while teaching James Joyce's "Ulysses." The work would inspire a discussion "about how she was recalling her modernist training, but working back and forth and making witty commentary about the nature of the medium, using different modes of representation in a single work."

Eventually, the needlework melded with her painting and drawing in a way that highlighted the highest potential of each, often inspired by the drapery folds or organic forms of the Bernini sculptures she loved so much. There were times she painted the thread or "drew" with it, incorporating different shades of black and brown to create a modeling similar to what she expressed in her drawings. In the mix were completely monochromatic stitched areas, representing the same subject as the other materials. These areas she built up as a kind of bas-relief sculpture to suggest depth in a more literal way.

Her daughters recounted how her interest in sculpture developed from using Sculpey clay to create figures to drape so she could draw them. "There was an overlap of materials that kept evolving," Abby said. The papier-mache and polymer constructs would go on to be cast as bronze sculptures. Later, she would collaborate with Margie, a landscape architect, on a key design element of a commission for the Bank of America Tower's atrium in Manhattan.

There are times in the work where there is clear division, and times when it is hard to tell where one medium ends and the other begins. Like everything else in her development, these pieces are not self-consciously engaged in theoretical dialogues. Here "medium" functions in its truest sense as material, as well as being a state between extremes, in this case art and craft. These pieces transcend that implied dichotomy or hierarchy and make them moot, as they contradict the assumed qualities of both practices, a quiet but absolute disruption.

Downstairs at Drawing Room

"Jane Freilicher and Fairfield Porter: Between Friends" is a small but significant exhibition of work by two mid-to-late-20th-century painters working in a naturalistic mode of expression. The show highlights the best in both artists' approaches to landscape and still life in intimate easel-size pieces as well as two large-format landscapes by Freilicher. It is a reminder of how strong Porter's influence was on the realist painters who found themselves in and around Southampton from the 1950s to his death in 1975.

It remains on view through Dec. 27. Ruddick's exhibition will be open through Jan. 31.