Nishan Kazazian has been making art for more than 50 years and practicing architecture for almost as long. “It can be challenging,” he said recently. “People try to pigeonhole you as either one or the other.” The two enterprises are distinct enough that he maintains websites devoted to each.

At the same time, he strives for, and succeeds at, establishing “an osmotic relationship between the two.” Navigating that relationship can be tricky, reconciling “how to become very unique, yet, in architecture, how to be very functional and economical.”

His work ranges from visionary architectural projects to plexiglass sculptures to virtual installations that combine digitally created sculptural elements with photographs of actual locations. What links all his work is receptivity to a variety of materials and technologies and fascination with transparency, reflections, shadows, mutability, and sustainability.

Mr. Kazazian, who lives and works in New York City and East Hampton, is of Armenian descent. His grandparents and his father, who was 6 at the time, survived the Armenian genocide, eventually setting in Beirut. He was raised and educated there before coming to the United States in 1972 on a Fulbright grant. He earned a master’s degree in architecture from Columbia University and a master’s in art and art education from Teachers College at Columbia.

A licensed architect, Mr. Kazazian has worked for large firms in the United States and abroad. He is co-founder and principal of A&A Design Group in Chelsea, which specializes in architecture, interior design, and the integration of art in architecture. His commercial and residential projects can be found in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania.

However, none of his executed projects appear on his architecture website. “The work I’ve built was not underlain by the philosophical ideas behind the new work. I put online things I want to do rather than things that I’ve done that I don’t want to repeat.”

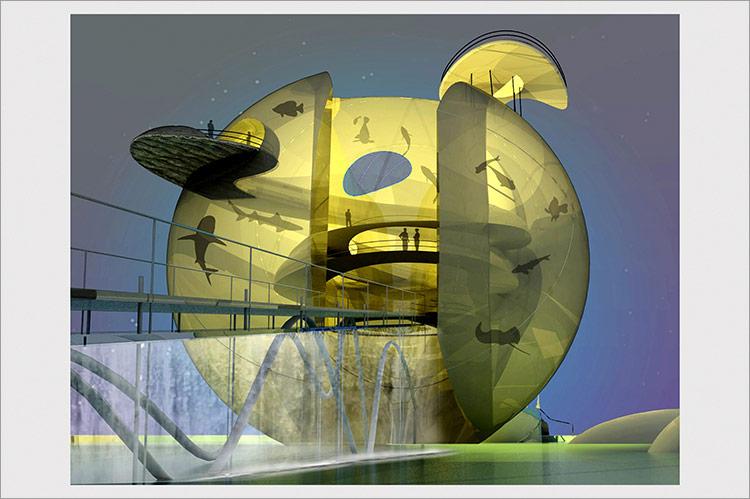

He calls his unrealized projects, among them a concert hall and an aquarium, “architectural explorations.” Imaginative and innovative, they are nevertheless fully spec’d, awaiting clients “with vision, who can understand how my work can enhance their lives without being economically burdensome.”

“Amphibian Concert Hall” is approached by a long ramp that extends from a beach to a circular structure elevated over water. Waves and tides trigger sound and light patterns as they touch the building throughout the day, but they can be muted during performances. Convertible platforms inside can change height and, depending on position, afford views of the landscape or the central stage.

“Virtual Aquarium,” is sheathed in transparent solar panels that generate power for the structure while allowing views of the outside. Instead of housing live aquatic creatures and vast tanks of water, the aquarium receives images from undersea cameras around the world that are projected onto the transparent panels. “Think how much we save. We recreate energy from the solar panels. You don’t have maintenance, and you don’t have to disrupt or displace marine life. Sustainability is not only about materials but about ideas.”

As early as 1975, while still at Columbia, he made a clay model of a sprawling underground retreat covered with roof gardens so as not to disturb the forest’s ecosystem. The project not only reflected his belief in living harmoniously with nature, but also derived from his childhood experience of the rooftop gardens of his family home in Beirut as well as such historical manifestations as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and Pompeii’s Villa of Mysteries.

Indeed, references to the art and architecture of other cultures populate his conversation. One of his unexecuted installations, “Masters, Slaves, and Collaborators,” places photographs of the powerful members of society at its top and videos of workers below. “Maybe this came from Egyptian or Mesopotamian murals, where masters were big and slaves were small,” he said.

Many of his virtual installations combine photographs of East Hampton sites with digital superimpositions. One is a view of Accabonac Harbor from Gerard Drive in Springs juxtaposed with transparent panels on which are projected ghostly images of some Mr. Kazazian’s family members from Marash, an Ottoman Armenian city.

“Some perished and others survived, eventually finding their way to Paris, Boston, Baghdad, Rio de Janeiro, and Beirut,” he said. In November, his work was included in a show in Paris that explored the relationship between architecture and art. Relatives came to the opening from all over the world. “For the first time ever all of my cousins were together.” He has brothers in Lebanon and in Greece.

The Paris exhibition included work from Mr. Kazazian’s “Fragmented Landscape” series, which, like his “Shifting Shadows” and “Conundrums” series, consists of multilayered plexiglass constructions that highlight the interplay of solid shapes, light, reflections, and shadows.

The components of some of these pieces can be rearranged at will by the artist, and different perspectives, shadows, and reflections emerge as the viewer moves around them. Transparent membranes or planes are central to his architecture, sculpture, and virtual installations.

Taken within the overall context of his work, the sculptures call to mind architectural models insofar as they involve the creation of three-dimensional spaces. While he makes use of computer design and drafting software, Mr. Kazazian believes strongly in the importance of drawing and model building.

In a 2012 letter published in The New York Times, he shared Michael Graves’s concerns about the “death of drawing” in architecture. “This is unfortunate, because the architect’s ability to create models with wood, cardboard, clay, and other materials adds additional understanding, not always apparent in a computer-generated model, of a structure’s spatial relations as well as its relationship to its environmental context.”

Mr. Kazazian is preparing a monograph of his complete works tentatively titled “Connecting the Dots: Architecture and Art.” A draft copy reflects the extent of his creative output from his undergraduate years at the American University of Beirut to the present. There are abstract paintings, wood constructions, sculptures, furniture, paintings on newspaper, and ceramics.

Some of the ceramic pieces were broken and reassembled. “I have practiced breaking and putting back together objects in my artwork since my teenage years. Later, I surprisingly discovered kintsugi, the Japanese practice of repairing broken pottery. By emphasizing the pottery’s fractures and breaks, instead of hiding them, kintsugi often makes the repaired piece more beautiful than the original.”

The discussion of breakage and repair turned to his father, who survived genocide to become a successful mechanic. “He built something from nothing. He was my example of how when you break things you can put them back together and take a new life, a new direction, always looking for the positive. Lamenting misfortune might be important for a certain amount of time, but then you learn from it, you take energy, and you go on. I think my work is about that.”

Mr. Kazazian bought his house in East Hampton’s Northwest Woods 20 years ago. He did not design it, but he made certain renovations, including adding a porch where “you can spend time indoors but feel outdoors.”

Behind the house are two identical prefabricated studios that he designed, “one where I can do dirty work, such as sanding, and another where I can do clean work.” The easy passage between the two buildings calls to mind the permeability he strives for between his art and architecture.