For most of the summer (and into the fall), the Drawing Room Gallery in East Hampton has presented a two-part painting show from a single source, acquired over several decades.

The collectors gravitated toward artists active during the height of Abstract Expressionism who chose instead to paint from nature.

"Painting Place" began with Nell Blaine, Jane Freilicher, Fairfield Porter, and Albert York. It continues through Oct. 26 with Lois Dodd, Sheridan Lord, and Jane Wilson. Although the early part is no longer on view, it is available in an online catalog, and it seems appropriate to think about the exhibition as a whole.

Originally conceived as a single show, the installation was to be stacked salon-style. These landscapes and interiors, however, breathe so much better with some distance between them on pristine white walls.

The paintings in each group work well with one another. Freilicher's layered expressive colors in oil produce an atmosphere that emanated off the linen supports and into the room, creating the effect of a luminous East End haze in their midst.

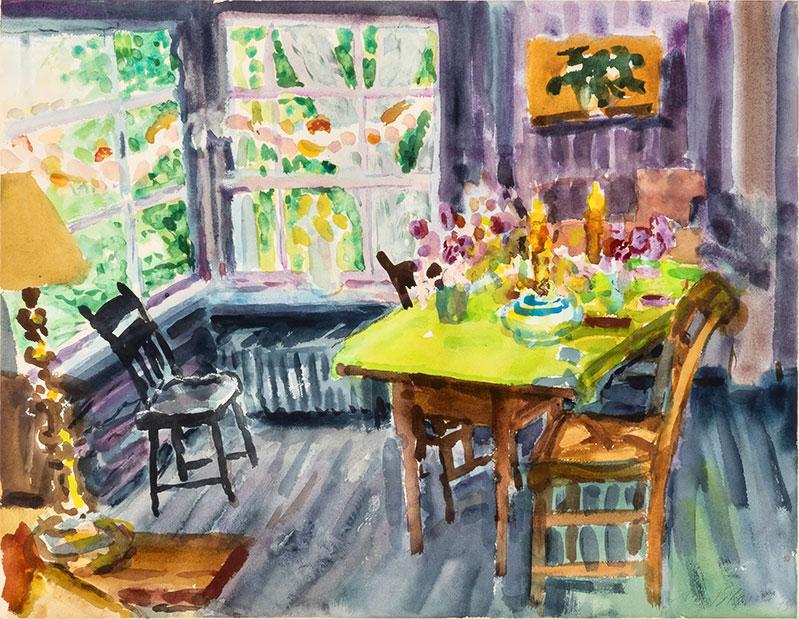

Blaine's watercolors corral color within linear borders that are loosely expressed but strongly defined. Her room and flower garden works are smaller than Freilicher's "Goldenrod Variations" (a hint of the artist's famed wit, playing on Bach's "Goldberg Variations"), but they held their own, with their saturated hues and dense compositions.

Freilicher did not make this easy. This painting in particular, shy of six feet wide, plays with realism and abstraction in vivid tones of yellow and blue. She defines a field of goldenrod in the foreground, but then dissolves it into a blur of flax on its march toward the blue pond in the distance and the houses on the opposite shore. It's suggestive, literal, and both at times, forcing the viewer to continually refocus and linger on each element. From the leafy fronds in the foreground, the small tree or shrub on the left, the airy and vibrating band at the center, and so on, it's impossible to imagine anyone tiring of this painting.

York's paintings are diminutive in comparison. A potted begonia on a sill overlooking an expanse of land in oil on wood measures around 10 by 9 inches. Set in the main room with a more subdued group of paintings by Freilicher and Porter, they worked well there, allowing for more contemplation than they might otherwise have received in the front gallery.

The Porter was placed on the wall perpendicular to York's begonias at the top of the stairs. There it functioned affably, a reminder that the more famous names in a show may not always produce the most exciting work.

His "View Through the Laundry Room Window," from 1951, is about as plainly direct as the title. What it did best was continue a secondary theme in the show: exteriors portrayed from the inside. The frank geometry of the sink, the windows, the sheets and towels hanging on the clothesline outside, and the lines on the wall indicating paneling or full wainscoting seems grounded in similar distillations of form as Stuart Davis practiced in the 1920s, just when the artists in Part Two were being brought into the world.

The section now on view is no less compelling than its predecessor's best moments. These artists may have shared a similar type of formal training and appreciation for nature, but each found his or her own path to how the elements of landscape would be expressed in their paintings.

Like Freilicher in Part One, Wilson emerges as the star here, with large and smaller later works, all low-horizon seascapes and all showstoppers in the main room. There is also a formative oil on canvas and some watercolors in the mix, which produce a mini-survey of her work through the decades.

In the presence of her late-career seascapes, one is reminded of her Water Mill attic studio -- all white walls and light-filled windows -- with a single painting on an easel resplendent in the otherwise hushed, Zen-like atmosphere. On these walls, set in an upper-floor loft-like aerie, there is a hint of that experience.

Wilson's daughter, Julia Gruen, recalled recently in an essay she wrote for the gallery DC Moore in New York City that her mother "painted cityscapes, portraits, still lifes, and even abstractions, but ultimately, her soul was most connected to landscape, and it is in those landscapes that she found her truest self." The observation echoes here in the deep feeling and personal nature of them, even while they cling to some semblance of realism.

Painted on site and directly from nature, Lord and Ms. Dodd's works don't share much in terms of style. Ms. Dodd's are recognizable representations that verge on a more personalized abstraction, a product of a single visit. Lord's are somber and diffuse, relying on the East End light to do much of the work for him over multiple treks to the same location.

Ms. Dodd's smallish oil-on-Masonite paintings here seem derived from essence more than substance. The Homer-esque "Pemaquid, August 10 1995" captures the feeling and movement of choppy water. "Reflection at Beaver Pond" is mysterious and hard to fathom; some of the compositional elements make sense as reflections, others don't.

Lord's most significant painting on view, "Long Island Beach," from 1973, is as timeless as the others -- the larger two from this period and the small works on cardboard from around 1960. The subject matter might change, but the hazy treatment is unwavering.

What's striking and wonderful about "Long Island Beach" in this setting is its converse relationship to Wilson's work in the space. Instead of the striated slivers of land and sea set up against an all-consuming sky, Lord gives us an alternate approach. He puts an easel in the middle of the sand, looking down the beach, dunes to the left and water to the right.

His immediacy, despite the duration of its creation, is a neat trick and contrasts beautifully with Wilson's meditative studio practice.