Toby Molenaar was 11 years old in 1939 when she climbed with her father to the attic of their house in Rotterdam and watched as German parachutes floated down over the city. The bombing and occupation marked the beginning of an adolescence shadowed by deprivation, the arrest of family members, and, along with thousands already fleeing the Dutch city, a harrowing several-hundred-mile journey on foot with her father and brothers to the home of family friends.

“You grew up very fast,” Ms. Molenaar said during a conversation at her house overlooking Upper Sag Harbor Cove. “My mother was always crying and scared, and my sister wasn’t very good at that either, so I was the one who begged, to get food for everybody. I became a person far, far beyond my age to be responsible for other people, and I think afterward I took it for granted that I could do anything.”

That fearlessness and self-confidence have informed a long career as a photojournalist, filmmaker, and writer whose work took her to India, Brazil, Afghanistan, the western Sahara, Lapland, Kenya, Mongolia, and Uzbekistan, among dozens of other far-flung locations. “I was involved in many situations where people said, ‘No, you can’t do that.’ I thought, who says I can’t? If I fall on my face, I fall on my face.”

The road from war-torn Rotterdam passed first through Switzerland, where, at 19, she married Ivan Doggwiler, a journalist, and had two children, Cathy and Marc. A friend, a commercial photographer named Steffi, bought her a camera and started her out on her career.

After the marriage ended in divorce, Ms. Molenaar moved to Zurich and took a job with Swissair. At the airport, she met “an American journalist who rated V.I.P. care, which made him part of my job,” she recalled in her memoir, “The Accidental Feminist,” published in 2014. The journalist, Fred Grunfeld, was a foreign correspondent for Time, Life, and other magazines. They married, and moved to Mallorca in the spring of 1961.

Not long after, her father-in-law transformed a large closet into her first darkroom. She already knew how to develop film, but he also gave her an enlarger and taught her how to print, which “added a completely new dimension.” On the island, she photographed windmills, baroque church organs in isolated villages, the Palma cathedral, ancient olive presses, fishermen, and -- adding captions or a few pages of text – began selling her pictures to Swiss magazines.

When The Daily Telegraph hired her husband to write about Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest, and the assigned photographer decided he'd rather take a studio job with Richard Avedon, Ms. Molenaar traded her old Leica for several new Nikons and stepped into the breach. It was her first professional challenge.

The trip took them from Vancouver Island into Alaska, where she photographed, among other things, a dramatic wavelike rock formation, totem poles, thunderbirds, and other totemic carvings. The magazine gave her pictures a double spread in what was the beginning of a long connection with The Daily Telegraph.

The pair traveled often to India, where her subjects included the Bengal Lancers, who lined up atop a hill and on command broke into a charge that was, she said, not only “indescribably better” than the one in the 1935 movie starring Gary Cooper, but also "truly terrifying.” Striking images of Buddhist monks at the ocean, a tribeswoman sitting on her roof in the Himalayan foothills, and a priest of Vishnu Shiva with religious markings are part of her portfolio from those trips.

In Afghanistan, where she was “a foreign woman amidst a crowd of turbaned Pathans, stocky Uzbeks,” and Turkmen, she watched men play buzkashi, a rugged equestrian sport in which mounted players attempt to place the carcass of a goat or calf in a goal. After one such contest, an older man lamented, “Men were not afraid to die in this game, and some usually did. Nowadays we have teams, and even rules!”

Shortly after one of the Grunfelds' last trips together, the El Camino de Santiago pilgrimage across northern Spain, their relationship began to unravel, though her work continued. In her first solo assignment for Life magazine, she covered a women’s football game in Shea Stadium. The magazine liked the story and published it, but went out of business soon after.

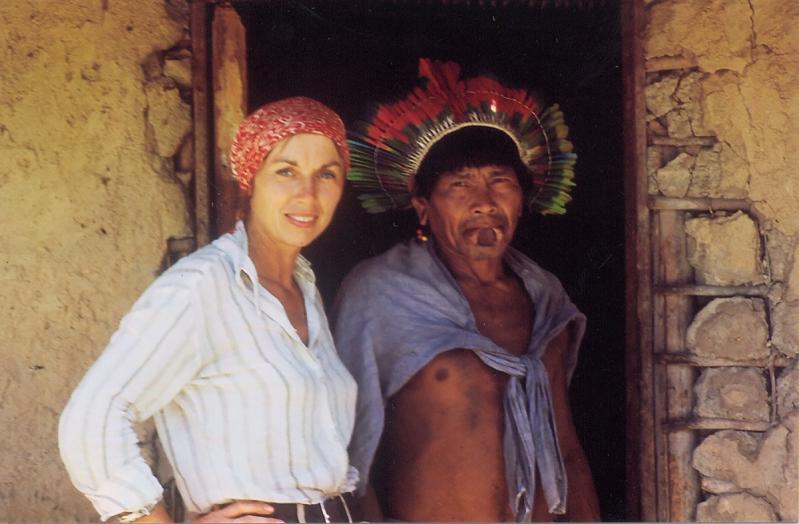

Several solo trips to the Amazon followed, where Ms. Molenaar photographed the construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway in the rain forest and -- although she was warned it would be dangerous -- an encampment of gold miners deep in the jungle. She was the only woman there, except for the prostitutes, but returned with photographs that testify to her gaining the miners' trust.

Looking back on that trip, she said, "It doesn’t seem it was all that difficult. You don’t just come in and take pictures. You ask, and you talk, and you make a combination of work and friendship.”

In 1971, after her divorce from Grunfeld, friends introduced her to Stanley Cohen, an American lawyer in Paris, where they lived for the next 20 years and had a daughter, Laura. Ms. Molenaar collaborated during that time with a friend, Meredith Martindale, on an article on Benjamin Franklin for Antiques Magazine. When the Éclair camera manufacturing company, a client of Mr. Cohen’s, owed him money, instead of a fee they gave him a 16 mm professional camera, which he in turn presented to his wife.

The result was “Benjamin Franklin: A Citizen of Two Worlds,” a film by the two friends that was a finalist at the 1978 New York Film Festival. In 1984, working only with a camera, a shopping cart, and “maybe, but not necessarily, a couple of lights,” Ms. Molenaar and Ms. Martindale made “Memories of Monet,” shooting at the gardens in Giverny as well as at the Jeu de Paume in Paris.

The actress Claire Bloom narrated the 28-minute film, which was bought by the Metropolitan Museum for its collection. In 1984, Ms. Molenaar told an interviewer for The New York Times that “the challenge lay in creating a play of light and color without being cute or coy or pretty.”

Several years later, housebound in Paris while her daughter Laura was ill, she began sorting through the artworks, music, stories, proverbs, facts, and legends she and Grunfeld had collected during their years in Mallorca, and decided the materials could be turned into a book.

The result, “Discovering the Art of Mallorcan Cookery,” was published in English in 1988 and subsequently translated into Spanish, Catalan, and German -- all the more remarkable because, she admitted, “I was not and am still not interested in cooking.” Be that as it may, based on that book, the Michelin-starred chef Alain Ducasse asked her to contribute a chapter to his own “Grand Livre de la Cuisine Mediterranee.”

The photographer was in her 60s when she undertook one of her most arduous challenges, UNESCO’S Silk Roads Project, whose mission, according to its website, was “to enhance our understanding of the dynamic cultural interactions that forged the diverse identities and heritages of the peoples concerned.”

“Silk Roads” refers to the network of land and maritime trade and communication routes that once connected the Far East, Central Asia, India, the Caucasus, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Mediterranean region. Traveling with scientists, scholars, and other journalists, Ms. Molenaar's charge was to document the architectural and cultural aspects of the trip.

Before he met his wife, Mr. Cohen owned a country house and mill in Sache, three hours southwest of Paris, where the artist Alexander Calder, who was a friend and client, lived. After leaving Paris in 1991, they began to divide their time between Sache and the East End.

“We had friends here,” said Mr. Cohen during the conversation in Sag Harbor, citing among them Joseph Heller, Saul Steinberg, and Larry Rivers. For three summers the couple exchanged their house in Paris for one on Drew Lane in East Hampton, after which Mr. Cohen bought a house in Water Mill and Ms. Molenaar’s son Marc built the Sag Harbor house for her. While the couple now live separately, they remain on friendly terms, and their many children and grandchildren from different marriages assemble in Sag Harbor for Thanksgiving.