Adversity and strife can often have a galvanizing effect on artistic expression. Picasso's "Guernica," novels such as "The Grapes of Wrath," punk rock, hip-hop -- none of these would have happened if everything in the world had been peachy.

As a result, it's said that political art often sprouts in hard soil. But sprinkle in an escalating crisis, like the potential for World War III, and suddenly it can flourish into a full-blown, socially charged piece of work.

Peter Buchman, an East Hampton artist, created the work "Constitution in Kremlin" in 2021. He described it as a play on words between the name of the Cyrillic-inspired font (Kremlin) that he used and a depiction of the United States in a Kremlin state of mind. The work now sits in a private home in Boston.

"Besides the irony, it's also scary," he said in his home last week. Mr. Buchman is a fourth-generation descendant of immigrants from Kyiv in the Ukraine. Mounted behind him, above the fireplace, was one of his giant works: a series of raised letters depicting slang words for various street drugs. "You just never know when our comfortable way of life might change."

The idea took hold in 2018, when he began feeling queasy about how chummy then-President Donald Trump was getting with dictatorial world leaders like Vladimir Putin and North Korea's Kim Jong-un.

"It just didn't go with everything we learned in American history class," he said, recalling his unease at the time. "And as an artist, I can talk about almost anything, especially things that are curious. Take Philip Roth. He'd be a guy to go down that rabbit hole of what if the Germans took over our country? What if they had won the war? So I began to wonder: What would happen if our Constitution was rewritten?"

As a result, he made a small study, about 3 feet by 3 feet, that spelled out the preamble of the Constitution of United States of America using the Kremlin typeface, and then painted the work somewhere between a pink and a brown.

"You could still read the English in that font but it had enough irony and creepiness that it made you stop and wonder what's going on," he explained.

He thought it was cool, but the painting sat in his studio for three years. Last year, rather unexpectedly, the DTR Modern gallery in Boston called to say that his work had piqued a client's interest and asked Mr. Buchman for images of his art. "I sent my usual 10 favorites but threw in the small Russian piece as well."

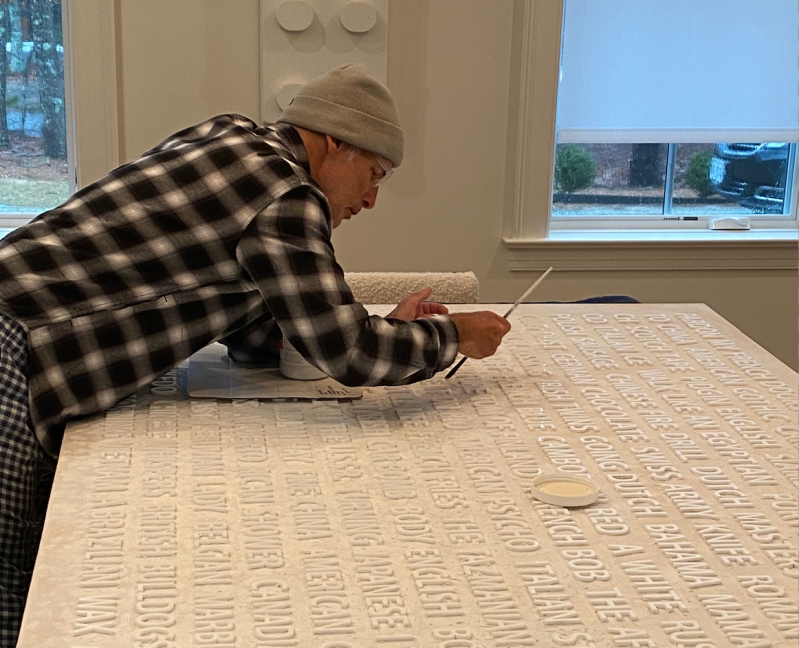

It resulted in the artist being commissioned to recreate and expand the Russian-American concept to a 10-by-5-foot installation that would include the entire U.S. Constitution.

Over three months, Mr. Buchman worked on the piece, searching the lengthy historical document to find passages that would hopefully challenge or move a viewer, as well as meet his client's requests.

"For instance, the impeachment reference is way down in the original and they wanted it up there," he said. He then sketched and designed the layout of the Cyrillic-styled lettering, and oversaw the production of the 3-D plexiglass letters. For shipping reasons, the piece had to go from being one panel to three. Then the gallery called to say that the client's interior designer had specified that the piece be painted in a particular color: Benjamin Moore's AF-290, called Caliente.

"That's a very alarming, daring, and dangerous color," said Mr. Buchman, and he suggested a wash instead. The answer: "No, we want you to walk into a paint store, buy that color, and use it," he said.

Mr. Buchman, a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, described the finished piece: "It has a real postwar, 1950s feel to it. It's a monolithic slab, reminiscent of Brutalist architecture -- all very daring and unusual for the Boston area, where people tend to be more traditional."

Trained as an illustrator, he began thinking about using words as sculptural material after a professor in a 2011 residency program at New York's School of Visual Arts noticed the profusion of words in his sketchbook -- columns of notes, rhymes, colors, and street slang. He encouraged Mr. Buchman to pursue a more conceptual direction in his work.

But it took another three or four years before the words manifested into ideas. "Where I could paint a picture without pictures, just with words that would made people think and process," he said. He continues to scratch the surface of language and culture in other epigrammatic works that explore race, immigration, and hatred.

"If I can make people appreciate a thought or an idea that they don't want to think about, or have never thought about, like hatred, then there's a beauty in that," he said.

And occasionally, a prophetic tinge.