How many times have you taken Hempstead Street in Eastville to avoid the backup at the turn from 114 onto Bay Street in Sag Harbor? That is likely how many times you have missed the significance of the street’s name to Eastville, Sag Harbor, and the entire East End of Long Island.

The road was named after one of the Eastville neighborhood’s earliest residents, David Hempstead Jr., and a kind of “forefather of the early Black residents of Sag Harbor,” according to David Rattray, the editor of The Star and a founder of the Plain Sight Project. He makes the statement in a homegrown film about this grassroots effort to reveal and relate the history of enslaved people and their descendants in the area.

“Forgotten Founders: David Hempstead, Senior,” directed by Sam Hamilton and Julian Alvarez, also local boys, will be shown at the Hamptons International Film Festival as part of its Views From Long Island shorts program on Monday.

The film has two focuses, one is David Hempstead Sr. — the father of junior — who was born a slave in Southold around 1774 and freed upon his owner’s death in 1805. He moved to Shelter Island and earned enough during his work as a farm manager at Sylvester Manor to buy 95 acres on the island to start his own farm. He died in 1843 when he fell off a boat that was sailing back home, after he visited his family in Sag Harbor.

The other focus is the work of the Plain Sight Project, a nonprofit started by Mr. Rattray and Donnamarie Barnes, who are its co-directors. The two came together after Ms. Barnes became involved with the history of Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island, first as a volunteer and eventually as director of history and heritage, and Mr. Rattray, with the help of summer interns, amassed names of more than 330 people of color in early East Hampton, of whom more than 220 were eventually confirmed as enslaved people.

That was a few years ago. He said this week that the number is now over 1,000 and includes names of enslaved people from Shelter Island, parts of Southampton Town, and additional research into East Hampton and Sag Harbor.

Mr. Hamilton, who since 2020 has made short documentaries on Sag Harbor residents for the Sag Harbor Cinema to screen before its feature films, said last week that the goal in making this documentary with his frequent collaborator, Mr. Alverez, was “to tell the story of the Plain Sight Project, the work they do, how they do it, and why it matters.”

They decided that simultaneously telling the story of an individual that the research had uncovered would demonstrate why it matters. The primary documents and other research that Ms. Barnes shared in relating the Hempstead family’s history illustrated how it was done.

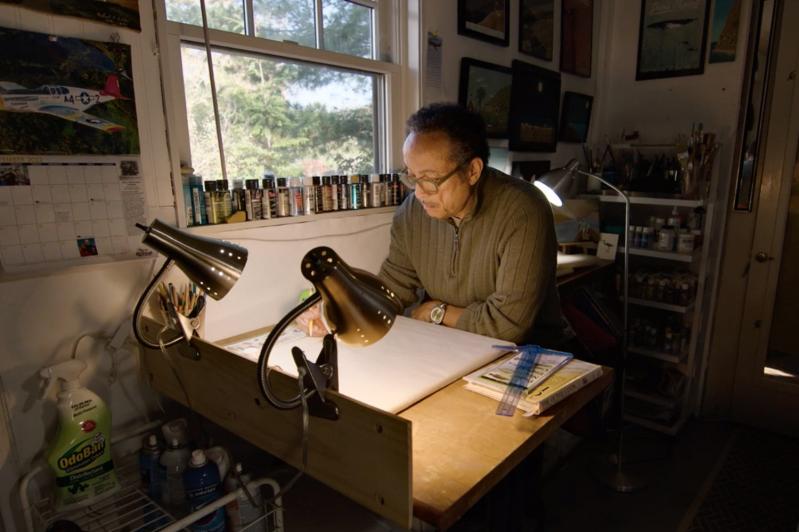

He added that Mr. Rattray asks in the film, “Now that we know, what do we do?” By commissioning Michael Butler to paint a portrait of Hempstead incorporating the stories the Plain Sight Project had uncovered, “we presented a possible answer to that. . . . As we learn more and more about Hempstead, the portrait gets more and more complete.”

For several years, Ms. Barnes had been researching the history of enslaved people at Sylvester Manor, which recognizes on its website that it is “the most intact slaveholding plantation north of Virginia.” Through grants and collaborations with Native American groups and archeological researchers, efforts have recently focused on identifying people buried in the property’s Afro-Indigenous Burial Ground, with more than 50 names discovered so far.

In the film, she discusses two boys sold into indentured servitude in 1829 to the manor’s owner at the time, Samuel Smith Gardiner. In the attic of the manor house, she points to carvings likely made by William and Isaac Pharaoh, who were brought to Sylvester Manor by their mother when they were 8 and 5 years old, respectively. They were late arrivals. The documented history of slavery at the manor goes back to 1653, when Grizzell Brinley married the plantation’s founder, Nathaniel Sylvester. She brought an enslaved African family with her: Hannah and Jacquero, plus their daughter, Hope.

When Ms. Barnes and Mr. Rattray met to discuss their findings, they were full of stories, many only recently uncovered. “We were both like ‘I can’t believe it. How come we didn’t know this,’ “ Ms. Barnes says in the film. The Plain Sight Project, formed in the wake of these discoveries, “asks the questions: Who was here? Where did they come from? Where did they go?” said Mr. Rattray.

The archives at Sylvester Manor and the East Hampton Library, census records, account books, last wills and testaments, and letters, were all there waiting for their secrets to be revealed. “The records really are in plain sight,” Mr. Rattray said. “It’s just a matter of looking for them, or rather even opening your eyes to them on the page, and not just passing over them.”

Standing at the corner of Liberty and Hempstead Street — named for David Hempstead Jr. — in Sag Harbor, Mr. Rattray noted in the film that it is one of the “very few streets that recognize a person of color” in the area.

For years, this portion of Sag Harbor avoided gentrification. It seeped in gradually at first, and more aggressively in recent years. “I think very few contemporary residents here even know anything about what its significance is.”

“The idea that you have Liberty and Hempstead together at a corner, I think sums it up,” he said. “That’s no accident.”

The film, which is 27 minutes long, will be screened at the East Hampton Cinema at 6 p.m. Monday. It will be shown in a program with “Merv,” a narrative short film by Sam Roebling, and “The Pedestrian,” a documentary by Nora DeLigter and Claire Read about a nine-day walk from Brooklyn to Montauk.