Michael Shnayerson, the writer and part-time Sag Harbor resident, famously tells a story of how he once gave Kurt Vonnegut a tennis lesson. It was one summer sometime in the 1970s, and the young Mr. Shnayerson and his late parents, Robert and Lydia, had rented the windmill at Quail Hill in Amagansett, where there was a tennis court. Somehow it was suggested that the summer kid in the windmill could help Vonnegut develop a Slaughterhouse second serve.

At about the same time somehow it was suggested that I, a local kid from the Amagansett lanes, might be available to mow Elliott Erwitt's lawn. The famous French-American photographer, who died in New York on Nov. 29 at age 95, had rented a house on Atlantic Avenue. My late parents, Marvin and Virginia, must have been at a cocktail party when someone who knew Mr. Erwitt came up with the idea.

Of the ensuing interview at the Erwitt house to which my father chaperoned me I recall only a thin portfolio of images. I must have spent most of the time looking at the ground. My father extolled my talents, a biased liar since my lawn-mowing resume included only one reference: our own on Meeting House Lane. And that was done with a manual rotary mower.

Mr. Erwitt's keen eye must have assessed my candidacy with immediate doubt. At the time I was known to my classmates at the Amagansett School as "Puny Kuhn-y." My potential first-ever mow client was likely wary of my being able to muscle any type of mower around his lawn. Moreover, he must have worried that anyone passing by while I was at the task would report him for violation of child labor laws.

I didn't make the cut.

My near-claim to grass-cutting fame came back to me last March in Paris, where Mr. Erwitt was born on July 26, 1928. The Musee Maillol in Paris's Seventh Arrondissement had mounted a superb retrospective designed to capture all of what Mr. Erwitt contributed to photography over his long career. The last major show of his work before his death, it ran until September this year.

There were the dogs, of course, which he did better than anyone. The Maillol made sure the dog theme was reinforced with dog prints stenciled on the floor to guide viewers through the photographer's various categories of work.

But any fears the retrospective would surrender to a prevailing sense of cute faded away quickly. You don't get asked to join the renowned Magnum Photo Agency, and later lead it as Mr. Erwitt did, with dog pictures alone.

All the major photographs that defined the multiple facets of his work were well represented. There was the Nixon-Khrushchev "kitchen debate," of course, and the unexpected and honest allure of Marilyn Monroe reading a script.

The big color commercial work represented in the show reminded us of how Mr. Erwitt reached a high level of professional capability while still being able to catch us off guard. Grace Jones, the singer, is a stunning beauty -- with stretch marks. His Andy Warhol portrait captures the painter's ghostly aspect in a way that makes all the other ghostly images of him look conventional.

Mr. Erwitt's impeccable sense of detail applied to such a broad scope of subject matter is what really stood out at the Maillol exhibition, and his career. That, and the vast whack of history his long life behind a lens allowed, puts him in a rare category. Like another famous French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, he developed his own science of the frame, rarely cropped.

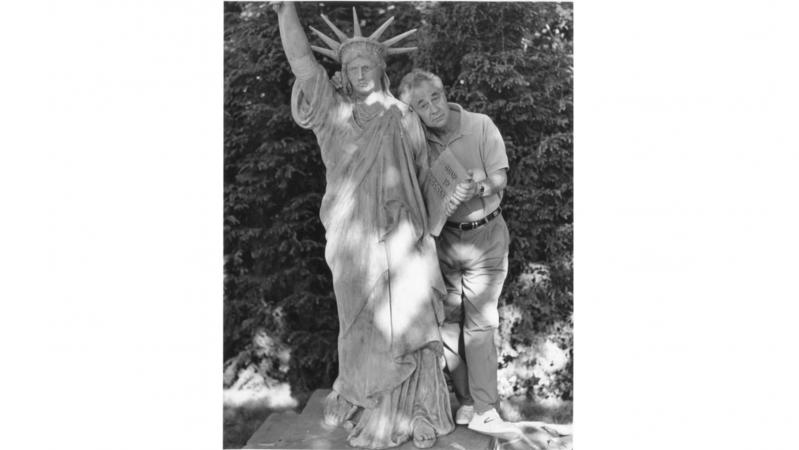

Naturally, the thing Mr. Erwitt will clearly be remembered for as much as anything else is that he never took himself or his work too seriously. He liked to laugh. The ironic and absurd in his work reflected a lot about the man. There's a great photograph of him in China long ago, wearing the surgical mask the pandemic has made ubiquitous today, but he'd cut a hole in it to smoke a cigar while he worked.

"I do take serious pictures sometimes," was one of many Erwitt quotes the Maillol put on walls over the exhibition's several levels. By the time you'd made it through the full body of work it was clear that he achieved the photographic equivalent of wordplay like few others.

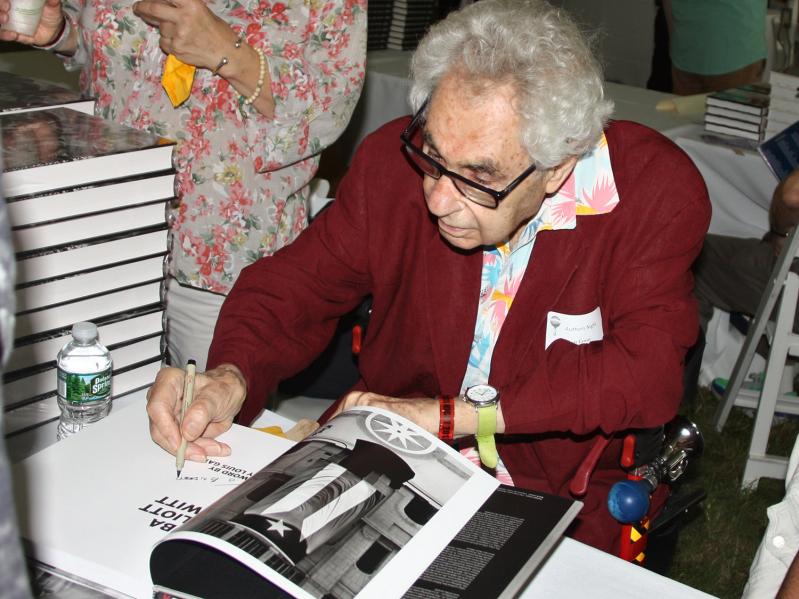

The Maillol show, created by the Tempora exhibition agency, in close collaboration with Magnum, was capped with a separate room full of Mr. Erwitt's equipment and ephemera, including his original marked contact sheets of well-known images. It offered a rare insight into how mind and eye witness history. It was also a bit like seeing the source code of a computer program revealed, in this case the thought process behind the final print.

The timing of his death last month has given his native France reason to celebrate him anew even though the Maillol retrospective has come and gone. Le Figaro magazine last week published a big spread of his work. And on the side of news kiosks all over Paris now, an album of his work for sale to support the work of Reporters Without Borders is prominently advertised.

Time was also friendly to Mr. Erwitt's brand of photography being more widely accepted and successful. In his New York Times obituary, he credits the serendipity of how photography became collectible with allowing him to buy his first house in East Hampton.

The accessibility and fun that mark much of the work probably helped bring on that era of collectability in the first place. Mr. Erwitt was a master at helping us learn through seeing -- and laughing, a welcome and enduring legacy available to everyone in the many superb books collecting his work.

Like a lot of kids growing up on the East End, proximity and serendipity offered exposure to great influences and extraordinary talents. I didn't make the cut mowing the Erwitts' lawn that summer, but later on my rock band played at Willem de Kooning's studio at parties when his daughter, Lisa, was a friend.

Seeing the Erwitt retrospective in Paris last March made me wish youth wasn't wasted on the young. If I'd known better back then, I'd have put on some muscle before that lawn-mowing interview. Maybe later on I could have leveraged local-kid grit into a darkroom assistant job or something. The Maillol retrospective made me think it might have been a whole lot of fun.

Eric Kuhn is a former reporter and news editor for The Star.