Carl Scorza has been painting since the early 1970s, but at that time he had no illusions about having a career as an artist. “I was not proud of those early paintings,” he said during a recent conversation at his studio in Springs. “They didn’t have a clear, organized thought behind them.”

He took part-time classes at the Art Students League and the New School, but it wasn’t until 1995, when he enrolled in a master class with the painter Wayne Thiebaud at the National Academy of Design, that the future came into focus.

Whether a painting is object-oriented or abstract, Thiebaud taught, the relationship to the rectangle, the integrity of the surface, and the demonstrative mark are universal. “It was a turning point for me, because after Thiebaud I realized I was getting older and that I had to do something, or I was just going to be a hobbyist painter.”

After that class, Mr. Scorza, who also had an apartment in the city, had a brainstorm. “I pitched the idea of making office space available to artists in the World Trade Center, and Jenny Dixon, head of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council liked it.”

A real estate development executive at the Port Authority liked it too, but “she had never heard of me. She wanted some better-known artists.”

At the time, Mr. Scorza was showing at the Lizan Tops Gallery in Manhattan, as was Graham Nickson, an Englishman who was the dean and a faculty member of the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting, and Sculpture.

The two artists met, and Mr. Nickson agreed to get involved. A program was launched that provided studio space in various areas in the center’s twin towers. “Graham picked the first group of artists, and he was astute enough to have recent graduate students, artists like me, but also well-established artists such as Rackstraw Downes, Yvonne Jacquette, and Richard Haas.”

Before long, the entire 91st floor of one of the towers became available, and the artists moved there. “I had never painted cityscapes before,” said Mr. Scorza, who produced several dozen canvases there, many of them views looking north to the Empire State Building. Because he had a full-time job, most of the paintings are nocturnes. In all, 140 artists participated in the program.

Not only did Mr. Scorza produce a sizable body of work, Mr. Nickson invited him to attend the studio school and offered him a full scholarship for the four-year program. He chose school over continuing at the World Trade Center and graduated in 2002, after which he came back to East Hampton to paint en plein air at the Atlantic Avenue beach in Amagansett.

Because he wanted to add figures to the outdoor experience but couldn’t very well ask beachgoers to stand still while he painted them, he took a course in écorché at the New York Academy of Art in 2004. (An écorché is a figure drawn, painted, or sculpted showing the muscles of the body without skin.) “It gave me a better understanding of anatomy,” said the artist.

After most of his beach paintings were sold by the East Hampton gallerist Terry Wallace, Mr. Scorza wanted to return to urban subjects. In 2005, he proposed another residency program, this time to the National Parks Service, which had been inviting artists to paint national parks since the early 20th century and had, in 2003, acquired 22 acres on Governor’s Island.

The parks service signed on to a program of classes for artists. Mr. Scorza managed it, and Mr. Nickson agreed to pay for the teachers and cover the insurance. Mr. Scorza spent three years there, both painting and teaching.

In contrast to the World Trade Center paintings, “The view was reversed, so that I looked up and out from ground level at the looming skyscrapers, and my work reflected more of the geometry of the buildings and their harmonic intervals,” he wrote in a catalog for a show last year at the Lucore Art Gallery in Montauk.

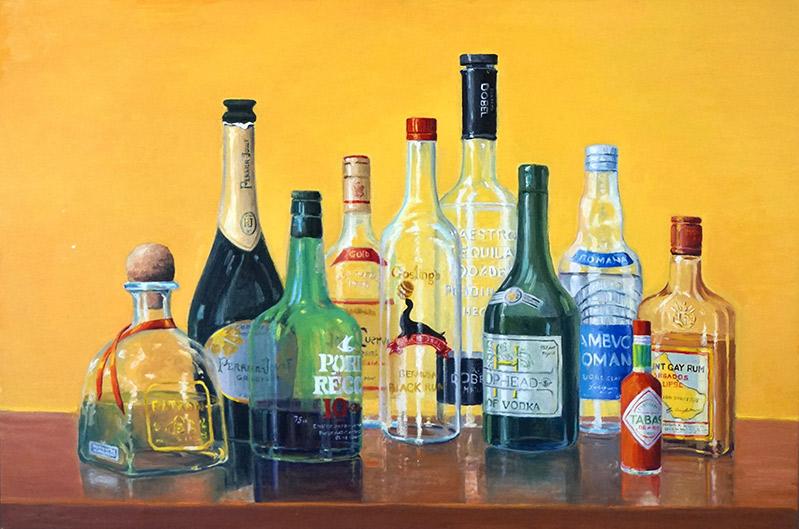

In that same show were several paintings from his still-life series of liquor bottles and glasses, begun during the pandemic. “Everybody thinks I got Covid and just kept drinking for the next three years,” Mr. Scorza said with a smile. In fact, “The beauty is in the arrangement and painterly display of bottles, their labels, the light on the glass, and its translucent nature.”

The first bottle painting reflected the artist's ongoing interest in compositional geometry, mimicking the motif of a view he'd painted from the World Trade Center.

While some of the titles, such as “Harbor Bistro,” suggest the compositions were photographed or painted on location, Mr. Scorza explained that each one is made from multiple photographs. In fact, all his paintings now emerge from a collage process, which starts with a drawing or a photograph, in some cases both. He merges the images in the computer, borrowing elements of each, cutting and pasting, scaling them up or down. When he’s satisfied, he prints out a collage. The process enables him to arrive at a composition he's happy with before moving on to the painting itself.

His most recent still lifes refer to more traditional arrangements: a bottle or two, or a glass, nestled on a table with a lime wedge, a saltshaker, or, in one case, a pistol. That painting, inspired by a scene from the James Bond film “From Russia With Love,” is titled “Shaken Not Stirred.”

Mr. Scorza was born and lived for three years in the Bronx before the family moved to Yonkers, where he attended high school. From there he joined the Navy, attended the 1999 Woodstock Festival, hitchhiked around Europe, worked as a set painter at a theater in upstate New York, and made posters for the ice cream king Tom Carvel.

“Because of Carvel, I met a lot of people in the printing business,” he recalled. That led eventually to his running a print shop in New York that employed 100 people.

Mr. Scorza cited as a source of inspiration an aunt who'd had success as a painter in Puerto Rico. “She would paint en plein air, and I picked it up. Most kids draw. I started before my teen years and never stopped.”

Sunsets have been a recurring subject in his work, from some of his Governor’s Island paintings to more recent compositions, many set on the East End.

“The sunsets are something I’m sort of philosophically associated with. The idea of the demonstrative mark, of drawing into color, the relationship to the rectangle, the integrity of the surface, these are all underlying things that are universal in painting -- at least, people believe they are. Well, so are sunsets.”