‘From the age of 11, I knew I was going to go to Pratt,” James Hamilton said during a conversation in his Springs living room. “I was always drawing and painting, so I figured I would go to Pratt and study art.”

The best-laid plans took a turn in 1966, the summer after his sophomore year in college. He needed a job that summer, and a friend knew a photographer who was looking for an assistant. Mr. Hamilton knew nothing about photography, but he went to see the man, Alberto Rizzo, who’d just left Rome to start a new life in New York City.

“We hit it off, and he hired me. I had to learn on the job — how to print, how to work in the studio. And by the end of the summer I decided I’m going to be a photographer.” Rizzo was a fashion photographer, but Mr. Hamilton found himself much more interested in taking spontaneous photographs on the streets of the city.

Over the course of the next four and a half decades, shooting everything from celebrities to war zones as a staff photographer for The Village Voice, Harper’s Bazaar, The New York Observer, and more, his street photographs have always occupied a prominent place in his work.

A documentary on Mr. Hamilton, “Uncropped” by D.W. Young, will have its premiere here in Sag Harbor (also in New York and Los Angeles) on Friday, April 26. In it, Kathy Dobie, a journalist and his companion since 1989, tells him, “In the street photographs, you capture the split second. A lot of times it shows almost a kind of loneliness in people, but also the choreography of street life.”

While working for Rizzo, he was also immersing himself in the work of other photographers. “It was a very exciting time in magazines and fashion photography. Avedon was at his peak, and all these great photographers were really stars.”

When he left Rizzo’s studio in 1969, Mr. Hamilton drove to Montana and from there hitchhiked around the west, winding up in Lewisville, Tex., which was about to hold what turned out to be the sole iteration of the Texas International Pop Festival.

At a local stationery store, he and his girlfriend forged press passes, claiming to represent Show magazine.

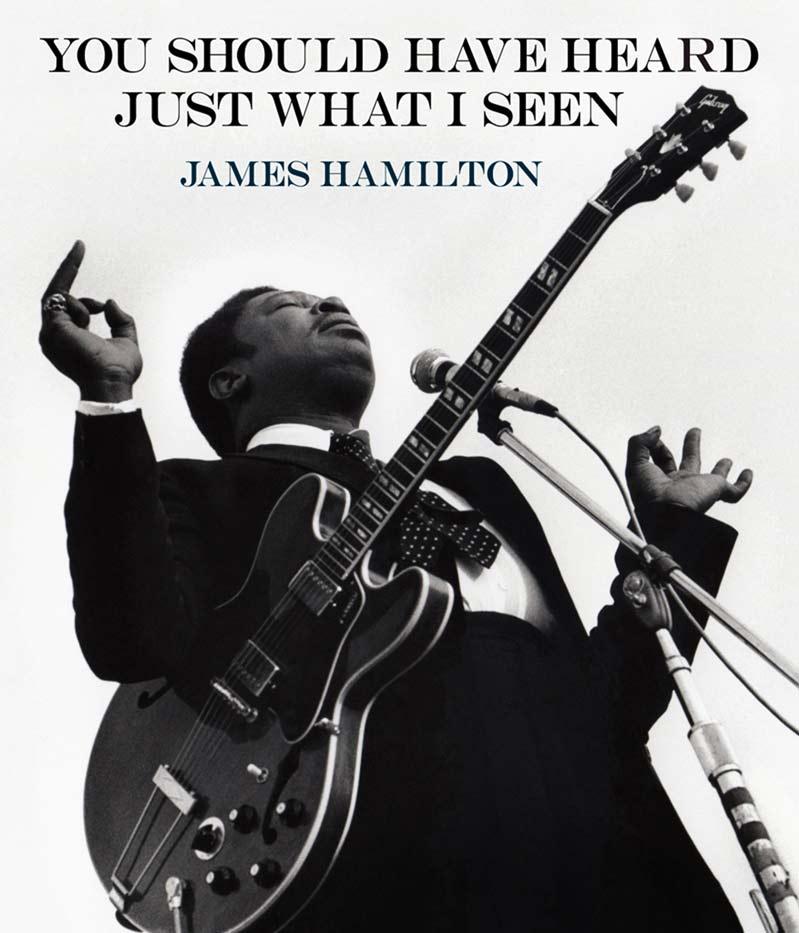

“I knew nobody would check that, and they gave us passes to be up front all three days. I got some great pictures of Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, B.B. King, and a whole bunch of great groups.”

He hitchhiked back to Manhattan, built a darkroom in his apartment, processed the film from Texas, and took it to Crawdaddy magazine (“the first magazine to take rock-and-roll seriously,” according to The New York Times).

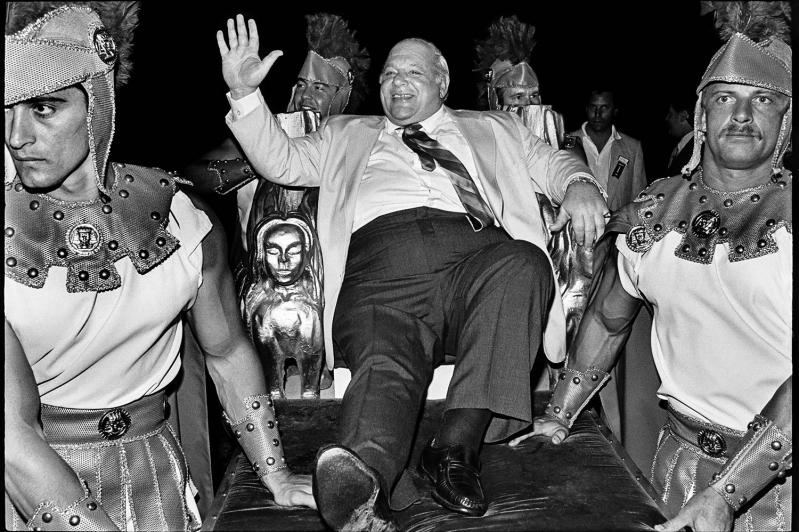

Crawdaddy hired him in a New York minute as staff photographer. He stayed until 1971 before moving on to Harper’s Bazaar. “The powers that be at Hearst,” he recalled, decided to make the magazine more competitive with Women’s Wear Daily — “more newsworthy and up-to-date.” He was their “party photographer, their fashion show photographer, but in addition I did lots and lots of portraits.” The job gave him entree to “just about anybody who passed through town that I wanted to photograph.”

In 1972, Alfred Hitchcock, one of Mr. Hamilton’s cinema heroes, was in New York to promote his film “Frenzy.” “I went to the St. Regis, where he always stayed when he was in the city, knocked on the door, and he opened it. There were no public relations people. His wife, Alma, ordered up tea, and I spent the whole afternoon talking and photographing, but mostly talking with Hitchcock.”

Mr. Hamilton’s enthusiasm for movies started early -— with Hitchcock. His mother took him to see “Rear Window” when he was 8. “That film influenced me, in the sense of seeing somebody doing not only what they love but never knowing from day to day what it would be. Which is the life I’ve had.”

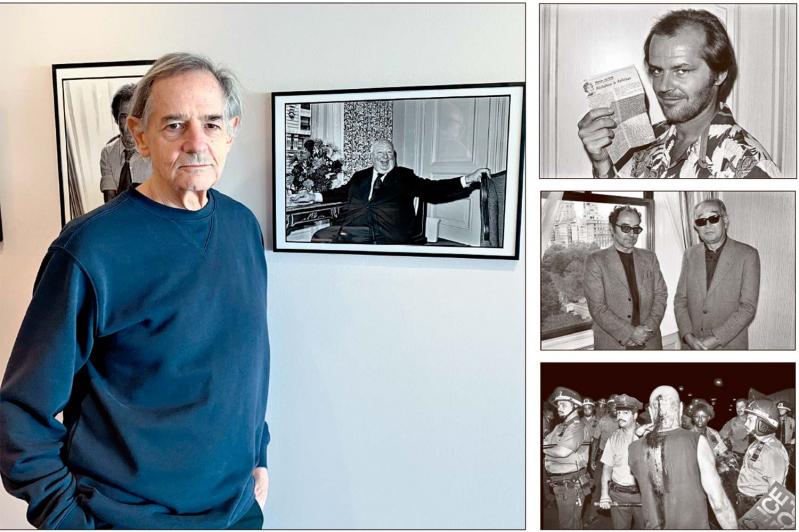

Along with a sneak preview of “Uncropped” last month, the Sag Harbor Cinema showed three films selected by Mr. Hamilton: “Rear Window,” Wes Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums,” and George Romero’s “Knightriders,” and opened an exhibition of his photographs in its third-floor gallery, which can be seen through mid-May.

Romero, perhaps best known for “Night of the Living Dead,” was one of the filmmakers Mr. Hamilton most admired during his long tenure (1974-1993) at The Village Voice. Hoping to meet him, he suggested a piece about him to The Voice’s film critic, and wound up spending two days with Romero in Pittsburgh, during which the filmmaker asked him to shoot stills for his movies.

He spent the summer of 1980 on the set of Romero’s “Knightriders,” an action picture that was Ed Harris’s first major role. While he was there, the writer

Stephen King, who was a friend of Romero’s, came to visit. “Stephen, George, and I would have dinner together and talk about movies — what else?”

Mr. Hamilton also worked on the sets of Mr. Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums” and “The Darjeeling Limited” and Noah Baumbach’s “The Squid and the Whale,” among others. Uninterested in photographing what the movie camera was seeing, “I did what I would normally do, which is make a documentary; that is, a photo story of the making of the movie. I would do all the backstage stuff. Photographing the life of the making of a movie was fun.”

It’s a long way from film sets and music venues to China’s Tiananmen Square, but that’s where, in 1989, The Village Voice sent Mr. Hamilton, along with the writer Joe Conason. “As soon as we got there all the murders were happening in the square. Students told us about a warehouse that was being used as a morgue, so we broke in at night, and I’m on my knees and Joe’s unzipping body bags, and I’m taking pictures of bodies.”

Warned that guards were approaching, they fled. Couriers got the film back to The Voice, and Mr. Hamilton’s shot of a corpse ran on the cover. “Nobody else had those pictures,” he said. “The students were risking their lives to help us.”

Subsequently, London’s Sunday Times hired him to cover war and famine in Ethiopia, with Mary Anne Fitzgerald, a British aid worker and war correspondent. “It was probably the most terrifying thing I’d ever done, since we were under fire all the time. I found that in certain situations, I was more worried about my life than the pictures. You can’t be stupid, but at the same time you have to get the job done.”

He worked for The Observer from 1993 to 2009. Jared Kushner, who was already a developer, owned it toward the end of his time there, and Mr. Hamilton was sent to Brooklyn Heights to photograph a Corcoran real estate office. On the way there, he was run down by a Cadillac Escalade. “The wheel was on my leg. It separated my foot from my leg. It took me four years and four surgeries to be able to walk.” February 2009 was officially the end of his career as a photojournalist. He still takes pictures all the time, but not for publication.

While he was laid up, Thurston Moore, who’d launched a publishing venture called Ecstatic Peace Library, suggested they collaborate on a book of his photographs of musicians.

“James Hamilton: You Should Have Heard Just What I Seen: The Music Photography” was published in December 2010. Its 300 pages open a treasure trove of previously unpublished black-and-white photographs of music icons, ranging from B.B. King, taken by Mr. Hamilton in 1969 at the Texas Pop Festival, to Jerry Lee Lewis, James Brown, the Ramones, Patti Smith, Ornette Coleman — the list goes on and on.

In his introduction to the book, Mark Jacobson, an old colleague from The Voice, writes, “For Hamilton, music is the intersection with the divine, up-tempo or down in the gutter with the blues. Professional that he is, Hamilton has always accepted the assignment, and, infused by magic, he fulfills it.”