Kerry Sharkey-Miller took to photography at an early age. When she was 15, her grandfather gave her his Leica camera. “He was one of those people who tinkered with everything,” she said during a conversation at her house in Sag Harbor. “I found old odd-sized negatives of his, mostly military photos from World War I. It wouldn’t surprise me if he somehow used random pieces of film. I always liked that kind of experimentation.”

Her photography in the past decade or so has involved experimenting with different substrates, one of which is aluminum. Her process begins with a specific type of clear film. She starts by taking digital photographs, working with them in Photoshop, and then printing them onto the clear film digitally, with pigment-based inks.

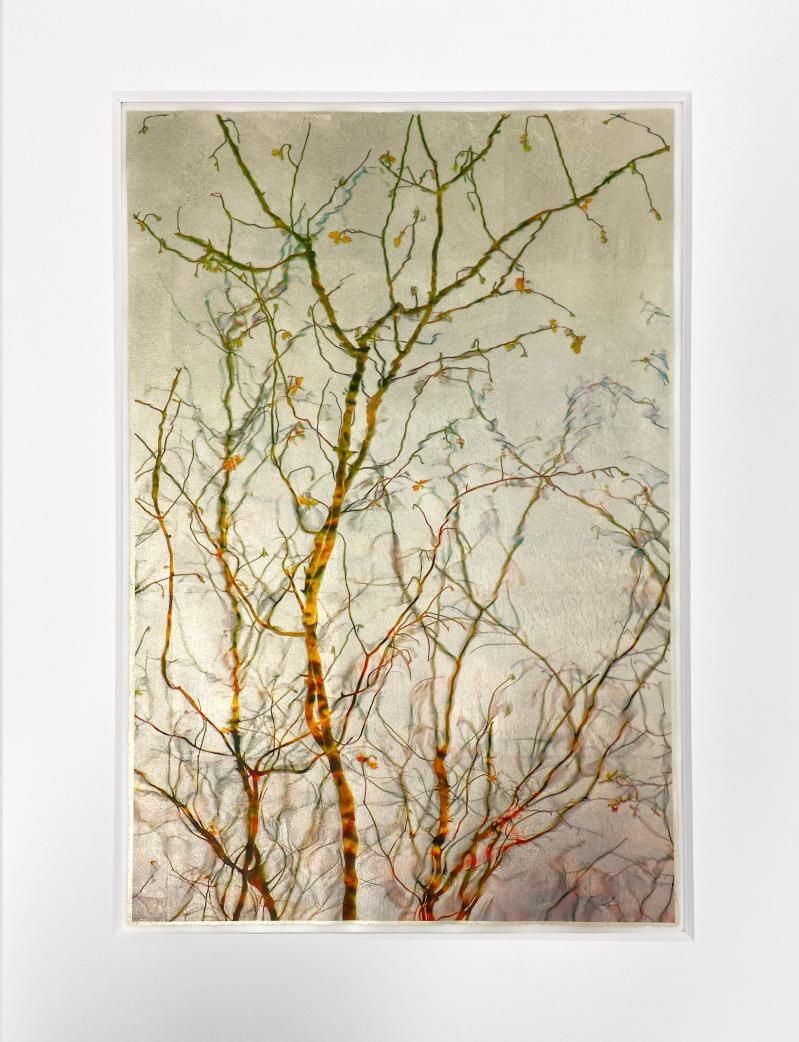

Next she turns to the aluminum sheet, which becomes the “atmosphere” for the image. She soaks the aluminum in OxyClean for several days until it becomes tarnished. She then sands out and polishes the area she wants to highlight behind the image. A solution of alcohol and a gel medium releases the image from the film directly onto the aluminum substrate. The images are then sealed with wax.

Trees, especially trees in winter, are one of her favorite subjects. “I love to shoot in the fog because I can drop out backgrounds easily. The trees have so much personality,” and they emerge almost mysteriously from the oxidized and polished aluminum.

Another favored subject is wildlife, including birds. In images of an owl and an eagle, the polished area of the aluminum is circular, suggesting both a halo and a moon. She can use the same images several times, because the oxidation process yields different results every time.

For another series of images, Ms. Sharkey-Miller prints the photographs digitally onto vellum, which is translucent by nature, but not transparent. She then varnishes the surface with a spray medium that increases the vellum’s transparency and applies a sheet of gold leaf to the reverse side. The gold leaf lends a luminescent quality to the image.

Ms. Sharkey-Miller was born in Glen Cove, but grew up in Southampton. Because she wanted to study photography, she left high school early, since “the only way you could study it at that time was with BOCES” (the Board of Cooperative Educational Services).

Once she started with BOCES in her junior year, she was able to take photography courses at Southampton College, and she earned her high school equivalency and put those credits toward her college degree. She eventually graduated with a B.F.A. in photography.

Over the next several decades her life took some twists and turns that led her away from photography. She worked summers at the Lobster Inn restaurant in Southampton from the mid-1970s to the early ‘80s. Because her husband, Scott, was a surfer, they would spend winters on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. “It was a very interesting place. I always say that I had my retirement when I was in my 20s.”

Ms. Sharkey-Miller and her husband, who is a house painter, moved to Sag Harbor in the early ‘80s, and in 1987 she and her mother, an artist, opened Southwest Studio Connection, an art gallery in Southampton. “We wanted to represent my mother’s work, and we were interested in both art and craft.”

At a visit to a craft fair in Massachusetts, Ms. Sharkey-Miller and her mother met Ray Tracey, an internationally known jeweler born and raised on the Navajo reservation in Arizona. “I loved his work, so we invited him to have a show with us.” He introduced them to other Native American artists and they decided to concentrate on Indigenous artwork from the Southwest.

Not long after they opened the gallery, “the stock market crashed. Nobody was buying art, but they were buying jewelry.” With a high concentration in fine art jewelry as well as some sculpture and painting, they continued the gallery for nine years.

On her frequent visits to the Southwest, she would always add a couple of days to her trips in order to explore the area. “It was the first time I ever heard silence. I just got up early one morning on the Navajo reservation and went out to Window Rock and at that time you could walk out into the hills and it was silent. There was no wind going through trees, just absolute silence.”

In fact, after her husband fell off a roof, breaking his back and shattering his heel, the couple considered moving to the Santa Fe area. “One day we noticed these black vehicles going down a dirt road, and there were guys waiting there with guns. We decided that was weird. It ended up they were opening some wells that had been abandoned years ago and had started fracking there.” That put an end to their plans to relocate. (Her husband did recover fully.)

After the art gallery closed in 1996, Ms. Sharkey-Miller became interested in 3-D animation. She took courses in New York City and met a man who lived on the East End and was teaching Softimage, a 3-D software. He hired her to work with him.

By 1998, the Ross School had opened its high school, and a friend who worked there suggested she apply to teach animation. “I ended up doing more stop-motion when I taught, rather than computer animation.” Stop-motion involves objects, rather than animation cells.

Ms. Sharkey-Miller also taught digital photography and traditional photography. “My background was in the darkroom,” she said. “I loved the darkroom. I think that’s why I’m so drawn to the experimental nature of the work that I do. I loved seeing that magic in the darkroom.” However, while she still does some cyanotype processing, she has been shooting primarily digital since digital cameras came out.

She had thought she would be able to focus on her fine art photography while at Ross, but it didn’t work out that way because “so much of your energy goes into teaching, and nothing was left when I came home.”

While at Ross she traveled for three weeks every year with students and created a body of images shot in Kenya, Morocco, Peru, Brazil, Australia, and New Zealand. Whether it’s an elderly couple displaced by floods in Peru, a Masai warrior in Kenya, or a boy with a puppy in a Brazilian favela, it’s clear she has the trust of her subjects.

She left Ross in 2012 and freelanced in two different areas. A contractor her husband worked with was building several houses, and he and the architects were looking for an architectural photographer. She worked for several different architects and builders. Her commercial work is stunning, but because houses take two years to build, there were time gaps.

So in 2013 Ms. Sharkey-Miller began to work as an art handler, and she still does, hanging shows at the Parrish Art Museum, Guild Hall, the Southampton Arts Center, and The Church in Sag Harbor. “It’s freelance, so I’ll work for a couple of weeks at a time and then I’ll have time off. So that’s when I started getting back to doing my own work.”

She has won awards from numerous juried photography competitions, has exhibited frequently at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, Mass., and elsewhere in this country, and closer to home, has shown at the North Fork Art Collective’s gallery in Greenport, and will have a two-person show with Charlene Ortiz at the Sag Harbor studio of the artist Dan Welden.