"A lot of stuff early on came from not knowing any better," said Tucker Marder, recalling his first months in the M.F.A. program at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. "Like showing up to grad school and thinking we have to do something crazy. Not worrying too much about it and just going for it as much as possible."

Judging by a recent conversation on his family's land in Springs, it would seem that his work since has been more -- not crazy, maybe, but certainly out of the ordinary. Over the past dozen or so years, Mr. Marder has created, either alone or with collaborators, a dizzying variety of multimedia works that could be called performances, projects, happenings, but that in the end defy categorization, because they are all those things and more.

His parents, Kathleen and Charlie, are well known as the founders of Marders Nursery in Bridgehampton, but they first met as art students, at Ripon College in Wisconsin. Tucker's brother Silas went to Bennington and his brother Mica went to Emerson College in Forest Row, England, "so we all had the art-school experience."

But the art spark ignited much earlier. "I know it sounds cliche, but I think being introduced to abstract art at a younger age, growing up around here" was a factor, as was his experience at the Ross School, where, he said, he not only had some inspiring teachers but also met Christian Scheider, a friend and frequent collaborator.

After graduating from Ross, Mr. Marder went to Pratt institute, where he majored in sculpture, "because at that point I thought sculpture meant you can do anything. I made all kinds of weird sculptures, about horseshoe crabs, or butchering deer -- always with animals or nature in some way," both of which continue to inform most of his work.

Birds, especially ducks, have figured prominently in Mr. Marder's life. Soon after arriving at Carnegie Mellon, he was surprised to learn that the National Aviary, this country's only independent indoor nonprofit zoo dedicated to birds, was his neighbor in Steel City.

He and his studio mate, Dan Allende, saw a show at the aviary called "Parrots of the Caribbean," a spoof of the Disney film, in which parrots climb all over toy pirate ships. "We were amazed, so we decided to develop and pitch this completely narrative-free bird show that would showcase the birds' unique individual behavior."

Robert Raczka, writing in Pittsburgh's City Paper, called the result "a cross between a trained-animal show and a Dada performance." In a video on his website, Mr. Marder himself calls it "a visual symphony designed to inspire respect for the beauty of birds." He and Mr. Allende created a colorful variety of props with which the birds and a dozen costumed performers interact for the 30-minute show.

"For the Birds," like so much of his work, involves "figuring out how to engage with environmental topics in a way that doesn't make people disengage or turn off, or freeze people and make them not want to do anything."

Another Marder-Scheider collaboration, the 2014 "Galapagos," an adaptation of the Kurt Vonnegut novel of the same name, was performed at the Parrish Art Museum. Andrea Grover, then the museum's curator of special projects, had met Mr. Marder in 2013, when he was selected by Robert Wilson to exhibit in the "Artists Choose Artists" show.

"Galapagos" adapted Vonnegut's novel with live orchestral underscoring, satirical physical comedy, a large cast, and extraordinary puppets, costumes, and props. Among the actors were Sawyer Spielberg and Chloe Dirksen. Forrest Gray composed the music, Evan Desmond Yee designed the sets, and Isla Hansen, Mr. Marder's partner, created the costumes.

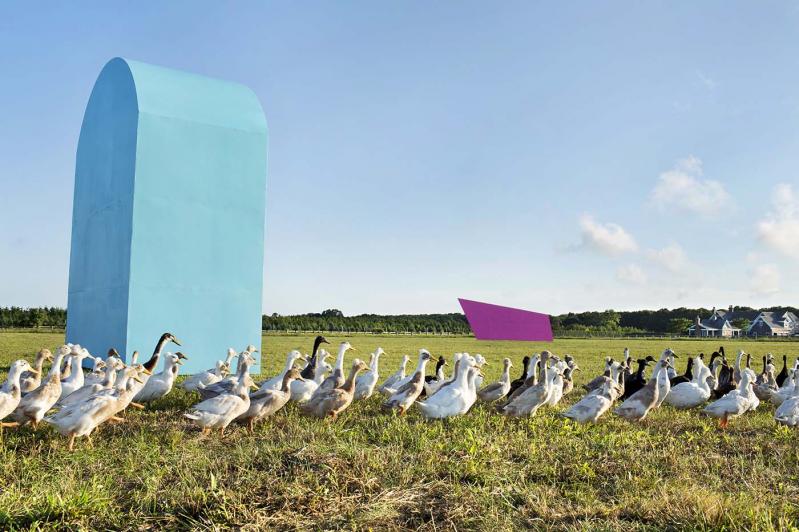

The following year, Ms. Grover invited Mr. Marder to create a Parrish Road Show for the museum's series of off-site exhibitions. The result was "Stampede" -- "a large-scale outdoor puppet show featuring 275 live, crested Indian runner ducks," in his words -- that was performed on a 35-acre plot of land in Water Mill.

While the audience watched from bleachers, the ducks were slowly herded along by two large plywood structures, one propelled by a diesel golf cart, the other by a box truck, both engines of locomotion invisible to the spectators. A third structure was stationary and occupied by Max Feldschuh, who played a vibraphone.

The shapes were influenced by aerial real estate photography, said Mr. Marder. One L-shape represented a flag lot, a trapezoid represented a plot of land seen in perspective, while the third had the shape of the rounded bay windows seen on big spec houses surrounding the field. His intention was "to be exuberant and optimistic about seemingly depressing and terrible things related to the environment," specifically the fraught relationship between real estate and nature.

While the performance was a one-time event, the preparation was another matter. To start with, Mr. Marder acquired 175 ducklings from a hatchery. "While we were herding them around the backyard, I realized we needed more." He drove to New Jersey and secured another 100 from a duck farm there. To get them all to Water Mill, he had to handle each duck and put it in a van. They returned to Springs after the event, and some of the original ducks' descendants are still roaming the Marder property, along with plenty of chickens and geese.

Mr. Marder finds inspiration in many off-the-charts sources such as the National Aviary, and they in turn generate ideas for new projects. "Rock Bottom," for example, was inspired by a swimming pool. In 2019, he and Ms. Hansen met a man who ran a gallery out of his parents' backyard swimming pool in Los Angeles. "I grew up diving, so the idea was to make this sunken reef of puppets and props that were addressing the pessimistic feeling that was going on in relation to Trump being elected, and every other aspect of life was depressing."

The 30-minute performance took place at night. Mr. Marder was underwater with a scuba hookah and a live-feed camera, whose images could be seen on a large poolside monitor. Ms. Hansen was in the pool with a clicker; when she held it under water and clicked it, Mr. Marder knew it was time to move to the next puppet or prop. These included a tombstone for Oscar the Grouch, a puppet newscaster at an anchor desk, a table and chair, and a rifle, among other objects and tableaus. Also half-submerged was Chase Ceglie, who played the saxophone during the performance.

As recently reported in these pages, Mr. Tucker is the proprietor of the Folly Tree Arboretum, which he founded in 2013 "to promote an exuberant environmental ethic through art and science." An archive of trees, it includes a sycamore that went to the moon, a tree whose fruits have become evolutionarily useless, an oak tree that owns itself, and many varieties of weeping conifer.

It also hosts a group of artists in residence for a period of two to six weeks. The program is currently by invitation only; artists are selected by a revolving pool of anonymous nominators. The initiative supports creative thinkers who develop new forms of environmental storytelling.

Mr. Marder and Ms. Hansen met while he was in graduate school at Carnegie Mellon, where she now teaches sculpture. He spends five or six months in Pittsburgh, the rest of the time in Springs.

He recently signed a contract to write a book about Folly Tree. It's no surprise that he is planning to create a puppet show that will represent the arboretum in a refrigerator-size object "that'll be like this live video puppet thing. The puppet show will be the book tour."

Stay tuned.