Aaron Parazette, an artist and the director of graduate studies at the University of Houston School of Art, decided it was time to take his first leave from the university in 17 years.

Since he has known Chris Byrne, the owner of the Elaine de Kooning House in East Hampton, since they met in Houston more than 20 years ago, he decided to get in touch to see if he could snag a residency there.

Mr. Parazette is now halfway through his seven-week residency. “I’ve come to think of it as the closest thing to what I had in graduate school,” he said during a conversation in the studio, “when all I did was eat, sleep, read, and work in the studio.”

Since earning his M.F.A. from the Claremont Graduate University in California in 1990, Mr. Parazette has had more than 20 solo shows and been included in over 100 group exhibitions nationally and internationally. His honors include a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, and being named Texas Artist of the Year in 2012 by Art League Houston.

Although creativity ran in his family — his mother and two uncles were artists — a move to Hermosa Beach, Calif., at the age of 1 set him on a different path.

“I lived two blocks from the beach until I was 23. I got my first surfboard when I was 11. Once I experienced the speed of being on a surfboard and being in the white water, that’s all I wanted to do.”

As a result, he spent six years after graduating from high school “living the California life, traveling the coast, just working hand to mouth and enjoying surfing.” The closest thing to making art was taking surf photographs of his friends.

However, in part because he had an uncle on the faculty at the University of South Florida in Tampa, he enrolled there in 1983, thinking he was going to become a photographer. Required to take foundational art courses, he became interested in other materials, and he graduated with a B.F.A. in painting in 1987. At that time, “I was making sort of gushy figurative paintings.”

Once in graduate school, he jettisoned figuration, influenced in part by the work of the Southern California painters known as “abstract classicists,” whose work he described as “reductive, hard-edged painting. There was a straight line from the work I was doing then to what I’m doing today.”

Mr. Parazette moved to Houston in 1990 as a Core Fellow of the Glassell School of Art at that city’s Museum of Fine Arts. That program was started by Allan Hacklin, the former head of painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, who had observed that when students leave undergraduate or graduate school, they often stop making their work.

“His idea was to create a bridge from academia to a professional life as an artist,” Mr. Parazette said. “That bridge amounted to a graduate program, without courses but with access to the facilities that every graduate department would have.”

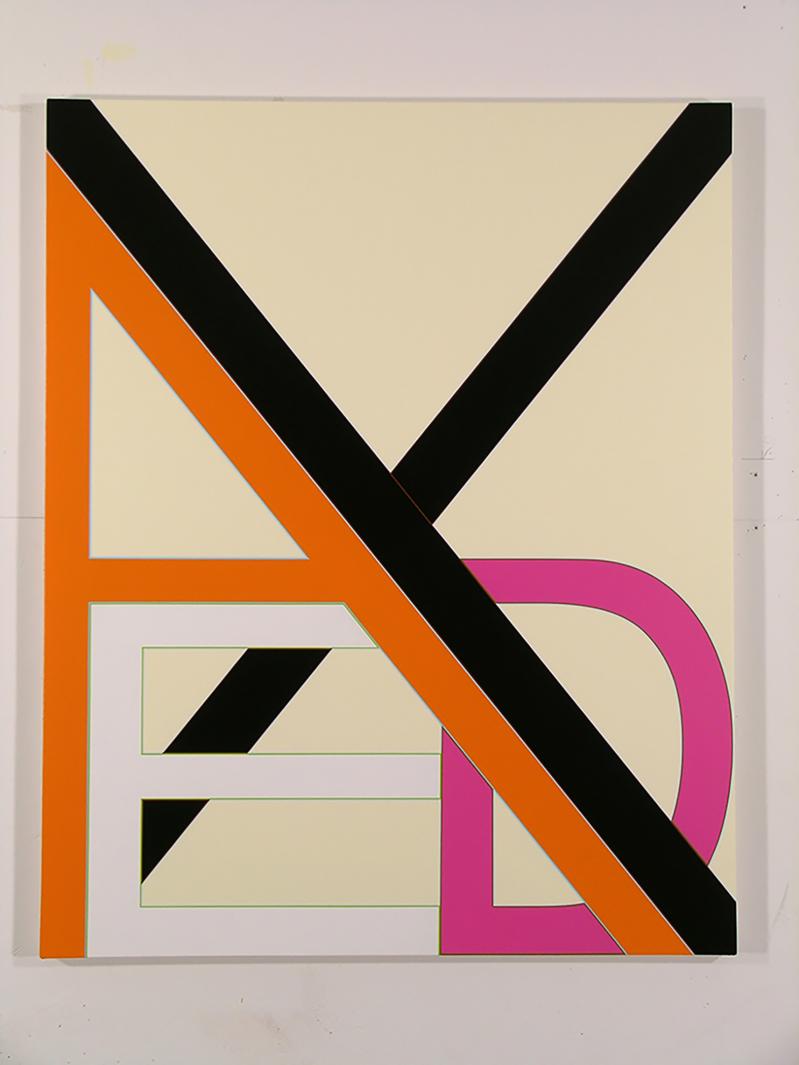

During a tour of the work in the de Kooning studio, Mr. Parazette brought up “Seinfeld,” the television show famously about nothing. “In an era where artists are called on to explain what their work is about, I could almost land on, ‘It’s about nothing.’ At the same time, you can see, standing in front of it, it’s tightly wound up and very precise and intentional.”

Over the past three decades, Mr. Parazette has produced a body of paintings that are resolutely abstract and nonreferential. They are linked by a concern with flatness in and of itself while at the same time exploring the possibilities for tension between flatness and illusion, as well as a painting as both a surface and an object.

The paintings in progress at the de Kooning house are a continuation of a series he has worked on over the years that involve shaped one-quarter-inch plywood supports that are covered with polyurethane before being tightly stretched with linen and painted. Some are irregular quadrangles, some ellipses, some circular.

“As soon as you’re working on a shape support,” he said, “that has a certain agency or insistence in terms of attention. Using color and form within that shape, I do something somehow responsive to the shape itself.” He pointed out an ellipse where the bottom was cut off to create a horizon line from which the shape seems to grow or emerge. The composition within that ellipse repeats the curve, but with variation and alteration.

Mr. Parazette said that when making the shaped supports the craft is in some ways akin to making a surfboard. And speaking of surfing, another recurring series, examples of which date from 2004 to 2022, is referential, but only insofar as it consists of rectangular canvases featuring letters that are jumbled versions of words. The first batch scrambled the letters of surfer slang, such as “aggro,” “stoked,” and “bitchin.”

While irregularity of shape and, in some cases, form characterize many of his paintings, others, some as early as 1991 and others as recent as today, are rectangular and linear with neither curves nor diagonals nor spatial illusion to speak of.

In addition to his paintings, Mr. Parazette has created a number of murals that engage on a large scale with issues of flatness, perspective, and illusion. One, “Blue Norther,” is 31 feet tall and 23 feet wide. Made in an office lobby in downtown Dallas in 2015, it consists primarily of shades of blue that ascend the wall in a geometric zigzag.

“It refers to the weather phenomena when a cold front comes south and meets a warm front and creates a sort of pyrotechnic effect and causes thunderheads,” Mr. Parazette told The Dallas Morning News. “My thought was that I would be bringing something of that weather phenomena into the space and synthesizing it with geometric abstraction.”

Another mural, “Flyaway,” from 2012, wrapped around two walls at Art League Houston, covering almost 400 square feet of space with flat geometric shapes and lines that converged in two focal points for a riff on perspective.

Of that mural, the critic Robert Boyd wrote, “You are enveloped by the painting just as you are enveloped by the gallery itself. ‘Flyaway’ loses the autonomy of an individual easel painting, but gains a dialogue with the architecture.”

Looking across the body of his work, many of the paintings look different from one another without departing from the underlying set of issues that engage him. While acknowledging those issues, Mr. Parazette emphasized that there is also a desire to “shift things and jump.”

He referred to a New Yorker profile on David Eagleman, a neuroscientist, who “talked about having a rotisserie of ideas because he realized that a focus on one idea and a continued focus on that leads to a stagnation. So you work on an idea for a period, and then you surprise yourself by working on something new. It doesn’t mean I won’t go back to that,” he said, citing his jumbled word paintings and shaped paintings as recurring series.

While the residency has been productive, he stressed that he considers teaching a pleasure rather than a burden. He just felt ready for a time out from his life of the last 25 years in Houston.

Mr. Parazette met his future wife, Sharon Engelstein, an artist, when both were juniors at the University of South Florida. They began graduate school together at Claremont in 1988, married a year later, and moved to Houston in the fall of 1990 to join the Core program together.

“We recently built our dream studio behind the house,” he said. “Sharon has the first floor with a full ceramic studio as well as office space. And I have a big painting studio on the second floor.”

So when the residency in East Hampton is over, he will have his own dream studio to go back to. As well as Ms. Engelstein and their daughter, Joy.