‘Eternal Testament,” the current exhibition on view at The Church in Sag Harbor, includes work in a variety of mediums by 16 Native artists from the East End and across the country. But it is more than the artworks, as captivating as they can be.

Underlying everything is that the exhibition, organized by Jeremy Dennis (Shinnecock) and Meranda Roberts (Yerington Paiute and Chicana), has been conceived to reaffirm that Sag Harbor, including the church, occupies the traditional homelands of the Montaukett and Shinnecock Nations. And by extension, it invites contemplation of such themes as forced assimilation, sovereignty, and survival that are critical to all Indigenous people.

The issues and themes were articulated during a panel discussion at the opening reception by Mr. Dennis, Ms. Roberts, and Denise Silva-Dennis (Shinnecock and Hassanamisco-Nipmuc), an artist in the exhibition and, as she said to the audience’s delight, “I’m Jeremy’s mom.”

Detailed wall labels illuminate the individual artworks and the artists, and two large wall panels, Essential History and Essential Glossary, elucidate the themes for visitors to the show.

Of the exhibition, Sheri Pasquarella, The Church’s executive director, said, “We are allowing them to reclaim space that is Indigenous land in Indigenous territory. So we’re asking the public to try exploring all the beautiful stories that are on view here, and the range of emotions the artists use to tell the story. There’s humor, there’s whimsy, there’s provocativeness, and then there’s earnestness.”

Mr. Dennis is one of the original board members of The Church. “I think a lot of art spaces want to be inclusive of Indigenous places and artists, so with me being a board member, I think we always had that as a goal,” he said during a conversation at The Church.

He met Ms. Roberts, a visiting professor of art history at Pomona College in California, when she curated an exhibition, “Still We Smile: Humor as Correction and Joy” at Idyllwild Arts in that state, and included works from Mr. Dennis’s “Rise” series.

“ ‘Still We Smile’ was an exhibition that highlighted Indigenous and Native American humor and the way we use humor to find joy and also bring attention to some of the things that more non-Native people need to be aware of when they’re engaging with people from our communities,” said Ms. Roberts.

“I thought the work she’s doing, the content and the focus, we had to bring that here to the East End,” Mr. Dennis said. “There are a lot of very deep and conflicting and difficult conversations within this show. I think they’re being communicated, but when you do it through a lens of recognition, pop culture, and humor, it makes it easier to enter into it.”

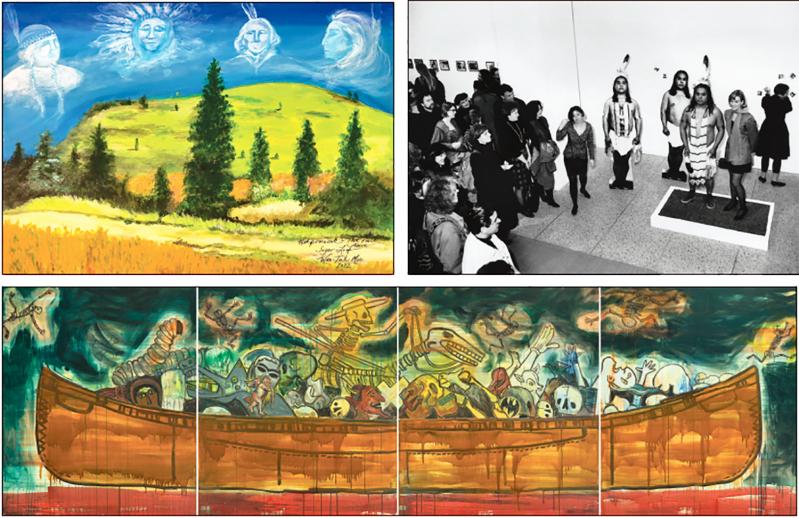

One example is “Take a Picture With a Real Indian,” photographic documentation of a performance staged at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1991 by James Luna (Luiseño, Puyukitchum, Ipai, Mexican, 1950-2018). Mr. Luna presented himself in different guises — traditional regalia, a suit, or everyday clothes — as a living tourist attraction with whom non-Native visitors could be photographed on a platform in the gallery. Mr. Luna described the piece as an act of mutual humiliation, implicating himself and his audience in perpetuating stereotypes, according to a wall text.

Humiliation, or shame, came up during the panel discussion. Speaking of the arrival of European settlers, Ms. Roberts said, “We were offering assistance, and the dominant narrative was that the Indigenous were considered ‘savage,’ their religions were outdated and needed to be corrected. . . . We feel shame about practicing some of our more spiritual practices out in public. Forced assimilation created a system where Native people no longer practiced those things.”

Ms. Silva-Dennis’s painting, “Ushpomuonk — That Space Above — Sugar Loaf” (2022), engages with the issue of protecting Native burial sites, one of which, Sugar Loaf, a sacred burial ground in the Shinnecock Hills, was returned to the tribe in 2021. The announcement came from the Shinnecock Graves Protection Warrior Society, of which Ms. Silva-Dennis is a member.

“My painting is about Sugar Loaf, which is about a mile west of the reservation borders,” she said during the panel discussion. “I can remember as a child my mom always pointing out that that’s where our people are buried, along these rolling hills.”

In the painting, there are four images of historic Shinnecock leaders in the sky. “I wanted to include two men and two women as culture bearers, as historical bearers, these are real people who lived, who taught us, who held the land for us,” said Ms. Silva-Dennis.

“Just a Sheepherder” (2022), a hand spun vegetable-dyed weaving by Tyrrell Tapaha (Diné) features a zigzag-outline technique unique to his family, a topographic map of an ancestral Utah settlement, and a mountain seen from their great-grandfather’s farm.

Another Diné symbol in the weaving is the whirling log, which for Diné people is a sign of good luck and good fortune to come, according to Ms. Roberts. As the exhibition takes pains to point out in a text, the whirling log is the same configuration as the swastika so commonly associated with the Nazi party.

“We understand that that symbol is harmful,” said Ms. Roberts. “How can we reclaim it as a sign of good luck for this Indigenous community and not be fearful of its connotations? The piece and the symbol speak to the land he comes from, speaks to the way as a queer artist he is working through this moment as well. And just being unabashedly Diné.”

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish, 1940-2025) was a groundbreaking artist who was given a retrospective in 2023 by the Whitney Museum of American Art, which noted that while her work engages with contemporary modes of art making such as Pop and neo-expressionism, in her own words, the work “involves contemporary life in America and interpreting it through Native ideology.”

“Trade Canoe: Don Quixote in Sumeria” (2005) is a monumental mixed-media work on canvas that takes up more than 16 feet of wall space. The canoe, says a text, “bears the weight of war, capitalism, and cultural erasure while testifying to Indigenous endurance.” Piled into the vessel are images from Picasso’s “Guernica,” skulls, crosses, a devil with a pitchfork, and other representations of violence and suffering. Despite that cargo, the canoe itself, a masterful painterly object, doesn’t sink.

On the subject of sovereignty, Ms. Roberts said that to not see tribal nations as self-determining is patronizing. “That’s what happened for a very long time, because the federal government thought they knew what’s best for us, and they still do sometimes. Which is why they put us in boarding schools, and why they took our languages from us. In actuality we know what we need to survive and what our children need, and I think that’s what this show does really well, which is exemplifying how artists are reclaiming that self-determination narrative.”

Mr. Dennis noted that while the Shinnecock people gained federal recognition in 2010, the entire Montaukett tribe was declared extinct in 1910 in a Suffolk County courtroom, while 150 tribal members were present at the decision. While the State Legislature has tried to reverse that, a bill to do so has been vetoed three times by Gov. Andrew Cuomo and three times by Gov. Kathy Hochul.

Along those lines, Mr. Dennis said, “Going back to Shinnecock, even though we do have federal recognition, you’ve probably seen in the news that we’re getting attacked for economic development, whether it’s the gas station, the Shinnecock monuments, or the smoke shops. These are just different ways we get income.”

“Eternal Testament” will continue through May 21.