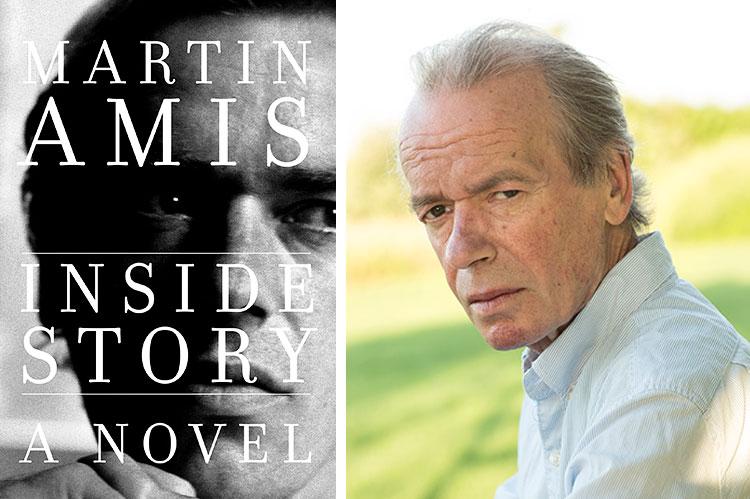

“Inside Story”

Martin Amis

Knopf, $28.95

Martin Amis's new work, "Inside Story," might well have come with a subtitle: "A Book About Death."

Knopf is too wise a publisher to allow such a bummer on the book jacket of one of its prized authors. But make no mistake, "Inside Story" is consumed, utterly saturated, with death. Paradoxically, it is also one of the liveliest and most entertaining works from Mr. Amis since his 2000 memoir, "Experience."

With snapshot memories, some written as memoir in the first person, some as fiction in the third, Mr. Amis gives us a tour of his literary life — from his penurious beginnings as editor at The New Statesman in the 1970s, where he first meets Christopher Hitchens, until the early 2000s, when he has settled as a literary lion in Brooklyn with his second wife, Isabel Fonseca, complete with outposts in Uruguay and East Hampton.

And what a literary life it is. Early in "Inside Story," the author apologizes for the name-dropping to follow, but even this caveat can't prepare the reader for the mother lode of literary celebrity stuffed between its covers. "Inside Story" indeed: Hardly a few pages go by where a Larkin, a Mailer, a Murdoch, an Updike, a Burgess, an Oz, a McEwan, etc., etc., etc., doesn't make some sort of cameo, and even dewy-eyed fans may have the fleeting notion that Mr. Amis vets his acquaintances for literary pedigree.

Of course the author is hardly an elitist, and an insistent self-effacement (and later, of course, the deaths) keeps things grounded. His relationship with an early girlfriend, whom here the author calls Phoebe Phelps, provides both mirth and pathos — mostly in the form of sexual humiliation. Ms. Phelps, whom young Martin approaches on the streets of London as a kind of lark ("you have to at least try, don't you?" he asks), has a figure like one of Mickey Spillane's secretaries ("tits on a stick"). He can barely believe it when she accepts his come-on and soon falls into the author's bed. The catch is that these sexual encounters culminate in . . . mostly no sex.

Somewhat absurdly, Phoebe ends up moving in with the author, even as his sexual frustration continues, suggesting a considerable insecurity in the young Martin. (There's material in "Inside Story" that both supports and subverts Mr. Amis's rep as a ladies' man.) The humor and pathos turn rancid, however, when the author ultimately ends up paying his girlfriend for consummation, beginning with "The Night of Shame," as the chapter is titled.

Later the humor valve is reopened with a scene where Phoebe dresses like a naughty schoolgirl to inflame the poet Philip Larkin, commonly known to have an erotic interest in female nubiles. The reader's instinct is to see this as literary hyperbole, but dramatized, the situation is so funny and ludicrous it couldn't dare be anything else but true.

Interspersed throughout are Mr. Amis's tips for fiction writers. Strange, you think? Out of place? Perhaps, in a book that is set on reckoning with death. But then the author has always been curious and highly articulate on the mysterious alchemy of fiction writing.

Experiencing writer's block? The author posits an obstructed subconscious: "I don't bang my head against the wall; rather, I stroll off and do something else. . . . It may take an hour, it may take a day, a night, two days, three nights, until I find myself again in the hard chair. . . . It means that the path is clear now." On the obsolescence of poetry, he is just as acute. "Serious fiction could respond to an accelerated world; but serious poetry couldn't. . . . The first thing it does is stop the clock. . . . But the speeded-up world doesn't have time for stopped clocks."

The meat here is saved for his relationships with Saul Bellow and Christopher Hitchens. With the Nobel laureate Bellow he will watch "Pirates of the Caribbean" on the telly (really) and travel to Jerusalem, which gives time for Mr. Amis to expound on Middle East politics. When Bellow's dementia sets in, Mr. Amis writes with real feeling on the tragedy of watching a great mind shut itself down. Invited to a writers conference together on the work of Joseph Conrad, Bellow says not a word until the very end, when he is asked what his novel "The Adventures of Augie March" is about. "About two hundred pages too long," he manages to quip.

The arc of Mr. Amis's friendship with Hitchens spans nearly the entire book, and is by turns hilarious, agonizing, tedious, and, finally, tremendously moving. Fast friends, they log countless hours in cheap dives near their editorial offices, spawning a lifelong habit of boozy, nicotine-fueled lunches. In subsequent years, a phone call with the message "The Hitch has landed" signals a Hitchens touchdown at Heathrow (and later New York or D.C.), which in turn meant a hard-drinking lunch that would often extend into dinner, and maybe even closing time; two friends whose lifelong conversation never ran out of material or affection.

Until, of course, there is the diagnosis of Stage Four esophageal cancer that strikes Hitchens at the height of his fame and influence. ("There is no Stage Five," the chemo-sick author would intone with a morbid smirk.) Mr. Amis is there for his friend for nearly all of it, the hair loss, the crushing pain, the incontinence — even traveling to Texas, where Hitchens undergoes experimental treatment.

Here Mr. Amis takes dead aim at America's shameful health care system. In his final weeks, we learn Hitchens was beset by financial worries — this a fully insured Vanity Fair columnist flush from an international blockbuster ("God Is Not Great"). "Yet there he was," writes Mr. Amis, "at his desk (in a gap between radio and chemo) with a stack of mail and a chequebook, wondering when he'd run out of money." Of wit, however, Hitchens was still brimming. " 'All agree,' said Christopher, 'that paperwork is the bane of Tumortown.' "

The end, though we know it is coming, is dreadful and shattering.

And now the body count really begins to pile up. His father, Kingsley Amis, his stepmother, Elizabeth Jayne Howard, Larkin, Bellow, and Hitchens, an interlude on the 9/11 attacks, on and on it goes.

Everywhere in "Inside Story" there is the sense of winding down, of ending. At one point, Mr. Amis announces that this will probably be his last long book. And the reader can tell, as he is loath to leave it. "Inside Story" feels a little long. Not "Augie March" long, but still; just when the book achieves full emotional resolution, the author tacks on no less than three codas, titled "Postludial," "Afterthought," and "Addendum," respectively.

Why, one wonders? Is it that the author didn't want to let go of his book of death because . . .

The subtext is there, of course, a manifest anxiety. Mr. Amis is now 71. There will be more, presumably shorter, books from this author. But "Inside Story" reveals a man hearing footsteps, the fourth coda not so far in the horizon.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels "Lit Life," "Gotham Tragic," and "Exposure." He lives in Springs.