“Being Ram Dass”

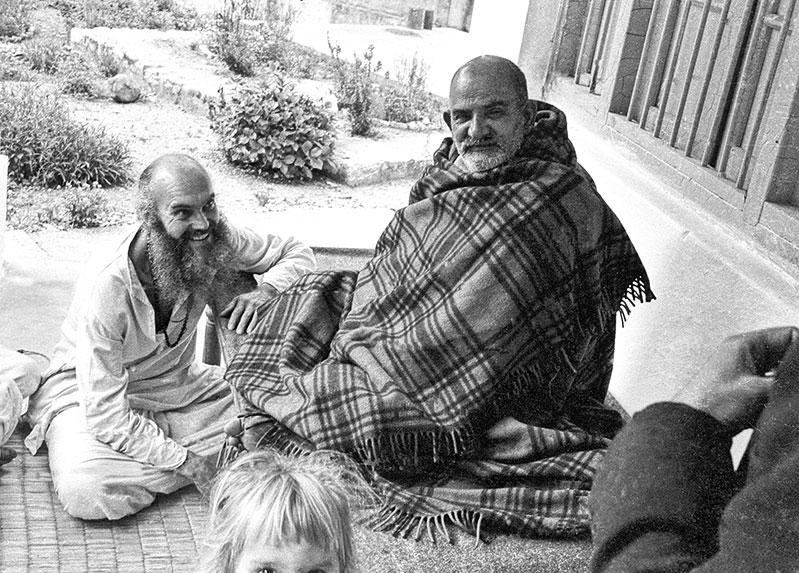

Ram Dass and Rameshwar Das

Sounds True, $29.99

"We are on the same journey home to the heart," Ram Dass wrote in the introduction to his final book. Dated December 2019, the same month in which he left his body, he summarized an 88-year incarnation thus: "This is a story of awakening from feeling separate and alienated toward living in oneness and love."

"Being Ram Das" is the memoir of a little boy in Boston named Richard Alpert whose remarkable journey took him from elite universities and high social status to points near and very, very far, including, in 1967, to the feet of a blanketed man in the Himalayas who, he wrote, delivered a greater high than Alpert's prodigious ingestion of hallucinogenic drugs could possibly effect.

The blanketed man, the Hindu guru Neem Karoli Baba, known to his followers as Maharaj-ji, would become Alpert's lodestar, bestowing upon him the name Ram Dass ("servant of God") and, after several months of teachings, meditation, and yoga, instructing him to return to the West and "be like Gandhi."

Dass was unsure, at first, what Maharaj-ji had meant by that, but he was soon giving lectures, helping to establish communal centers where Eastern spiritual practices are disseminated, and authoring more than a dozen books, the first of which, "Be Here Now," has illuminated to generations of Westerners alternate ways of perceiving and understanding existence.

Rameshwar Das, a friend of more than 50 years, was working with Dass on the latter's memoir when Dass died. Mr. Das, who lives in Springs, previously co-authored "Be Love Now" and "Polishing the Mirror: How to Live From Your Spiritual Heart" with Dass. As 20-year-old James Lytton, Mr. Das attended Dass's first talk upon his return from India, writing of that event that "Something shifted in me — the subtle sense of identity I had lived with since childhood, my self-image, my point of view." He too would travel to India and meet Maharaj-ji, who bestowed his new name.

Mr. Das and this reporter will discuss "Being Ram Dass" on Saturday from 5 to 6 p.m. via Zoom. The East Hampton Library is hosting the talk, and those interested in participating have been asked to call 631-324-0222, extension 3, or go to the library's adult reference desk. Registration can also be completed on the calendar page of the library's website.

A particularly consequential figure in 20th-century America, Dass takes readers through his midcentury upbringing in an affluent family, complete with a complicated relationship with his parents and confusion over his sexual feelings. Crucially, Alpert's early career as a psychologist, researcher, and professor fostered a hazy but inescapable understanding that the material wealth and status he was striving for were not in fact worthy pursuits.

"I played Harvard's power game," he wrote. "I straddled three departments and had a prodigious workload. I had the big corner office, three secretaries, and a number of research assistants. I was making good money, and I had my own apartment in Cambridge, which my mother filled with professorial-looking antiques. I had a Triumph motorcycle, my pilot's license, and a brand-new, sky-blue Mercedes-Benz imported from Germany."

Was it chance, or karma, that brought to Harvard a new psychologist, Timothy Leary? In the name of research, the two took psychedelic drugs, including psilocybin and LSD, both legal at the time. At the dawn of the earth-shaking 1960s, news headlines "were about the space race and the first astronauts circling the globe. We thought of ourselves as intranauts, exploring the unmapped worlds of inner space." Alpert, Leary, and others were "at the cutting edge of human consciousness," exploring both the therapeutic possibilities of psychedelics and the furthest recesses of their minds.

One experience led to the next. On one 1962 LSD trip, he "traveled through planes of consciousness that left me utterly mystified. I was still searching for a way to understand it when Aldous Huxley stopped by for a visit." The writer and philosopher brought with him a copy of "The Tibetan Book of the Dead."

"It was as if I was reading a travelogue of the worlds I'd just passed through," Dass wrote. "As Western psychologists, Tim and I had thought we were delving into unknown territory, making up theories as we went along to explain our experiences. But this ancient book from the East offered a detailed understanding of this very terrain. . . . The maps we'd been searching for already existed."

The death of his mother and "heat from government agents" — as more and more young people turned on, tuned in, and dropped out, in Leary's famous suggestion — were catalysts for his initial journey to India. A chance meeting with a 6-foot-7-inch surfer from California was a turning point. "There was something about him; I could feel Bhagavan Das knew something I needed to know," Alpert wrote. "When he said he was going on a pilgrimage to several Buddhist temples, I asked to go with him." He was also attracted to him, he wrote.

Bhagavan Das brought him to Maharaj-ji, and Alpert's account of this meeting is by itself worth a read of "Being Ram Dass." As he recalled, "Something inside me shatters. Or melts. Or dissolves. My spiritual heart cracks open, and something deep within, the part of me that has been hidden, releases in my chest, the heart chakra. I am pulled into my soul."

Now Ram Dass, he was given one mission by the guru: Love everyone, serve everyone, and remember God. Dass spent the rest of his life doing so, with several detours along the way. "I saw how necessary it is to bring social action and spiritual work together to truly deal with our own and others' suffering," he wrote. "My models were Hanuman," the Hindu monkey god, "and Gandhi serving God in the form of other people."

His efforts would include curing blindness with cataract surgery in India and Nepal; helping the homeless and Native Americans, the latter devastated by poverty and hopelessness; reforestation and redevelopment, and working with the terminally ill, including those with AIDS. "Compassion," he wrote, "is seeing others as ourselves, expanding our identity to include the other person."

Dass takes readers through his 1997 stroke, which struck as he was working on a book about conscious aging. "There were mind-boggling technological advances, like gene therapy and hybrid cars and space telescopes," he wrote of the era. "But for all the technology, we were still saddled with our very human reality. The discomfort of my body constantly intruded in my awareness, and my own mortality and that of others was poignant and ever-present."

More than an account of one man's fantastic voyage, "Being Ram Dass" is an account of America, tracing an arc from World War II through the explosion of new consciousness in the 1960s, thanks to psychedelics and Eastern philosophy's concurrent, benevolent invasion and their enduring imprint on the decades to follow.

Towering cultural figures including Allen Ginsberg and the musicians Charles Mingus, Paul Desmond, and the Grateful Dead appear, along with Dass's fellow travelers Robert Thurman, Sharon Salzberg, Jack Kornfield, and Wavy Gravy, among many others. The reader is transported to a time that, in these last days of Donald Trump's catastrophic reign, is at once familiar and foreign.

"The soul's game is not about reorganizing external life," Dass wrote. "It's not about getting a new job, friends, lifestyle; making more money or getting a new car; finding a new partner or a new therapist — or ignoring the family history. It's about inner reorganization, reorienting toward your soul."