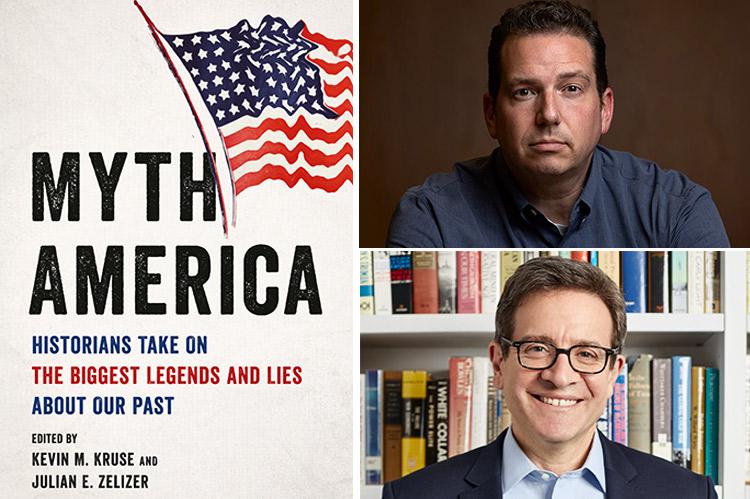

“Myth America”

Edited by Kevin M. Kruse and Julian E. Zelizer

Basic Books, $32

All myths carry a message, some benign, some pernicious. The 20 essays in the collection under review, "Myth America," deal with the latter kind as they continue to affect politics in America. All of these essays but one were written by professors teaching in major U.S. universities.

The overarching theme, the editors, Julian E. Zelizer and Kevin M. Kruse, write, is that "narratives of the past can distort the present" and in many cases do so intentionally to further political aims. "A new generation of amateur historians . . . lacking any training in the field or familiarity with its norms . . . write history that begins with its conclusions and works backward to find — or invent, if need be — some sort of evidence that will seem to support it."

I should add here that the professional norms in the study of history follow the rules of scientific investigation, including the requirement that evidence be verifiable from more than one defensible independent source — that is, as in a science experiment, capable of replication from a different source. Lore, versus fact, must be labeled as such.

The editors continue: "Although partisan motives animate much of the current crisis of misinformation, this volume also addresses a number of lies and legends that were born long before this moment and spread well beyond a single political party or ideology" and "have proved more stubborn than the partisan ones."

Such myths of note challenged in this volume include the notion that the Founders saw a distinction between democracy and republicanism and therefore, by implication, as we are a republic we are not a democracy. This is heard today more on the left than the right.

Akhil Reed Amar of Yale points out that while it is true that James Madison argued for a republic over direct democracy (as in pure populism), his point was the possibilities of representative government versus direct democracy: Republics "based on smaller representative assemblies could span large distances and encompass large populations," whereas direct democracy can work only on a small, local scale.

However, Mr. Amar provides numerous examples from participants at the time to show that most of the players at the Constitutional Convention did not make a distinction between democracy and republicanism. For example, among others cited, "the brilliant James Wilson . . . widely viewed as America's ablest lawyer . . . repeatedly and proudly [pronounced] the Constitution 'democratic' [saying] the people at large retain supreme power, and act either collectively or by representation."

In other words, so far as the Founders were concerned, the United States was and is a democratic republic.

David A. Bell of Princeton traces the history, from the Puritans to the present, of the term "American exceptionalism" and comments, "After September 11, 2001 . . . mainstream Democrats not only embraced the term but also found that its very emptiness made it strategically useful. They could happily profess their belief in American exceptionalism in the hope of winning over, or at least appeasing, voters who had very different ideas about what made America 'exceptional.' . . . But throughout the early twenty-first century the term continued to serve the purposes of the Right especially well, never more so than when Obama . . . the son of a foreign, Black, Muslim father . . . could easily be caricatured as the embodiment of . . . 'un-American values.' "

What are American values and what makes them exceptional? In her essay "America First," Sarah Churchwell, an American teaching at the University of London, quotes Louis Vitale from "Nativism Afoot in Our Politics Once Again": The "core message is simple . . . America belongs to those who consider themselves here first," meaning white people of European descent. Never mind that in fact they were not here first.

America First "has never been — and was never intended to be — a simple statement of patriotic self-interest. . . . On the contrary, it has consistently served as a divisive code camouflaged by its ostensible harmlessness . . . a story less about isolationism abroad than bigotry at home."

In a chapter titled "Insurrection," Kathleen Belew of Northwestern takes up the myths circulating about Jan. 6, 2021. First, on the claim that "this is not who we are": "Indeed, one can trace vigilante violence and lynching as foundational to American life and culture from the beginnings of the nation to the present," and she goes on to do so.

After presenting historical evidence to support this claim, she says: "The recent white power movement, however, is distinct in many ways from earlier mobilizations of racist vigilante violence in American history. Here I am talking about the broad and diverse social movement that brought together Klansmen, skinheads, neo-Nazis, militiamen, and more beginning in the late 1970s. . . . These groups united with the explicit goal of waging war on the United States and its democratic institutions." Further, "These activists were motivated by a sense of urgency: They believed that immigration, feminism, abortion, interracial marriage, and other social changes would lower the white birth rate."

It is worth noting here that according to a Brookings Institution analysis of the latest census, "whites" will make up only about 50 percent of the U.S. population in 2045 because, since the 2010 census, "racial and ethnic minorities accounted for all of the nation's population growth."

The myth of "this is not who we are" is compounded, in Ms. Belew's analysis, by the "lone wolf" myth, which claims that acts of social violence are perpetrated by disturbed individuals acting alone. "The most pervasive misunderstandings of the white power movement come from the 1980s, when its activists declared open war on the federal government and adopted an organizational strategy called 'Leaderless Resistance' . . . in which power activists could carry out individual small-group acts of violence on an agreed-upon set of targets with no demonstrable ties to other cells or group leadership."

And here's the worst news from Ms. Belew: "After the failure of the sedition trial" — in 1987-88, involving 13 conspirators whose collaboration was documented by Department of Justice wiretaps of hundreds of conversations — "the F.B.I. institutionalized a policy to pursue only individual actors in white power violence, with 'no attempts to tie individual crimes to a broader movement.' "

A fourth myth discussed in this collection concerns the belief propagated by Milton Friedman in "Capitalism and Freedom," which is that capitalism is the guarantor of freedom; but whose freedom? Naomi Oreskes of Harvard and Erik M. Conway of the California Institute of Technology, in the chapter "The Magic of the Marketplace," quote Friedman as saying that in a capitalist society "it is only necessary to convince a few wealthy people to get funds to launch any idea." In this manner "a free market capitalist society fosters freedom."

These days Friedman is received wisdom in the Republican Party and on the current Supreme Court. The reader can decide to agree or disagree for her or himself.

The remaining 16 chapters deal with myths about vanishing Indians, immigration, whether the U.S. is an empire, the border, why socialism cannot win in America (in this reviewer's professional opinion, because private property has always been one of the keystones of American liberty), whether the New Deal succeeded or failed, Confederate monuments, the Southern strategy of the Republican Party, protest, white backlash, whether the Great Society succeeded or failed, police violence, family values, feminism, the Reagan revolution, and voter fraud.

Not dealt with is Black Lives Matter, because, the editors say, "there has been such a robust debate over the role of slavery in American political development . . . we decided to focus our limited space here on other issues that have not received as much attention."

"Myth America" seems like a play on the title Miss America, a crown placed on the head of the supposedly most beautiful young miss (virgin?), hence most desirable female, in the country. Myth and pageant — benign or pernicious — intended to project some kind of national identity. How many American women today identify themselves with her, whoever she is?

Ana Daniel taught modern European history at Southampton College and had a 30-year career as a management consultant for a Wall Street firm. She lives in Bridgehampton.

Julian E. Zelizer is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University. He lives part time in Sag Harbor.