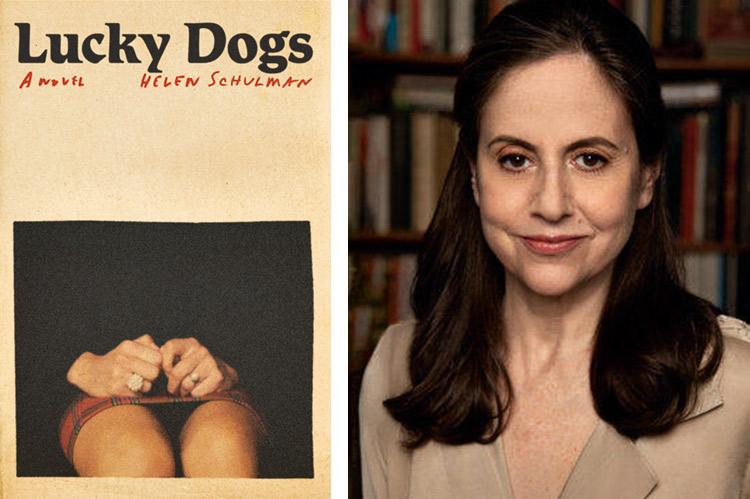

“Lucky Dogs”

Helen Schulman

Alfred A. Knopf, $28

What might to some seem like peeking at the end of a book is, in the case of Helen Schulman's latest novel, "Lucky Dogs," enormously edifying. And certainly important to what is going on right now in our world. And what has been going on for a very long time.

The last line of the final chapter is stupefying given the grotesquerie that has gone on before in this story: "I love that shot," the beleaguered, tormented main character — a stunning, savvy actress — says of a visual most readers might think horrific. But, of course, we've been on an unimaginable journey in this novel, through disgust and delight and back to appalling.

And that's where we land with the acknowledgments pages. The author's note is replete with emotion and wisdom, orienting us to the power these fictional characters derived from the author's spirit and soul. These are Ms. Schulman's words regarding her impetus to create these characters:

"As a teenager in the 1970s, growing up during the height of second-wave feminism, I truly thought things were only going to get better for women. . . . Well, we know how that worked out. Five decades later, I am furious on the best of days, and like a lot of women, I still often feel demeaned, underpaid, overworked, overburdened, and hypersexualized. When all the #MeToo stories broke — Weinstein, Cosby, Lauer, ad infinitum — I was so angry, I thought my head might explode. And yet I was not entirely surprised. Sadly, such abhorrent behavior is disgustingly familiar. But what was so shocking about this breakthrough round of reporting was the sheer scale of the crimes and the insidious web of those who enabled the people who committed them: that is, these entitled and protected mass rapists had been supported by other rich, powerful men and institutions as they committed one sexual assault after another. In some cases, they were also abetted by women in their employ or in their spheres of influence."

"The galvanizing idea for 'Lucky Dogs' came when I read a Ronan Farrow piece in The New Yorker about Black Cube, the private Israeli spy agency that Harvey Weinstein hired to intimidate and prevent the actress Rose McGowan from publishing her memoir, 'Brave,' which included McGowan's account of being raped by Weinstein. One of the two undercover agents assigned to McGowan was a woman named Stella Penn Pechanac, who befriended McGowan under false pretenses and betrayed her trust. As a child, Pechanac had been a refugee of the Bosnian War, escaping with her parents to Israel — yet another country caught in a perpetual, ruinous civil war. Reading more . . . I felt as if a story had fallen out of the sky. I was reminded of that famous quote attached to Michelangelo: 'I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.' Here was a narrative to which I could harness the inchoate, helpless fury I was feeling. My first question when I read about Pechanac was simply: How could one woman do this to another woman?"

A novelist's commentary more powerful than yet another news story. Ms. Schulman's is an Op-Ed piece that makes us sit up and take notice.

At the beginning of the novel, her protagonist, Meredith, a movie star, has absented herself from Hollywood to France, distancing herself from the vulgarities of her "business." Which is not so different from what she'd experienced growing up living in mobile trailers with gun-toting relatives.

Meredith's absentia is total: "I wore my flat expression in Paris like a lead apron, so no one could see the radioactivity inside." The entire novel is an implosion.

Ms. Schulman is astute in the ways she describes the treasures of Paris, including Berthillon, the luxurious ice cream and sorbet purveyor on Ile Saint-Louis, with its extraordinary view of Notre Dame just around the corner. She sets up her character, Meredith, in her flight, ordering a creme caramel salé.

"Even in a cute dress, the server here looked too tired and frail to be out this late at night assisting tourists. When she leaned forward to wipe the trickles of sweat from her forehead with her wrist, I could see telltale bands of silver roots in her dark hair's meandering part. I left her a nice tip — yep, I realized that in France gratuities are included, but this old lady was clearly exhausted, and I myself always felt lifted by a small token of appreciation back when I tended bar in Woody Creek. Then I grabbed my cone and scooted to the side so the woman behind me could fall in line. With all my leaping and scooting, I felt like I was part of a musical without the music. It was as if the whole scene in front of the ice cream stand were part of a show, and everyone else knew all the lines. Perhaps this feeling of inauthenticity was a symptom of a rare form of anxiety attack previously unknown to me."

" 'La meme chose, s'il vous plait,' said the woman behind me, that throaty voice."

Spoiler alert: This paragon of virtue who befriends Meredith — someone who picks up her own ice cream cone trash in the heart of Paris — is doing so only to curry favor with the target of her deceit. Who knew that picking up after oneself could be such a cover-up for . . .

Who will begin to understand, as this novel progresses, how terrifying glitz and glam can be?

Lou Ann Walker, professor of creative writing in the M.F.A. programs at Stony Brook Southampton and Manhattan, is executive editor of the literary and arts journal TSR: The Southampton Review. She lives in Sag Harbor.

Helen Schulman has long been a visitor to Amagansett, where her mother owned a house.