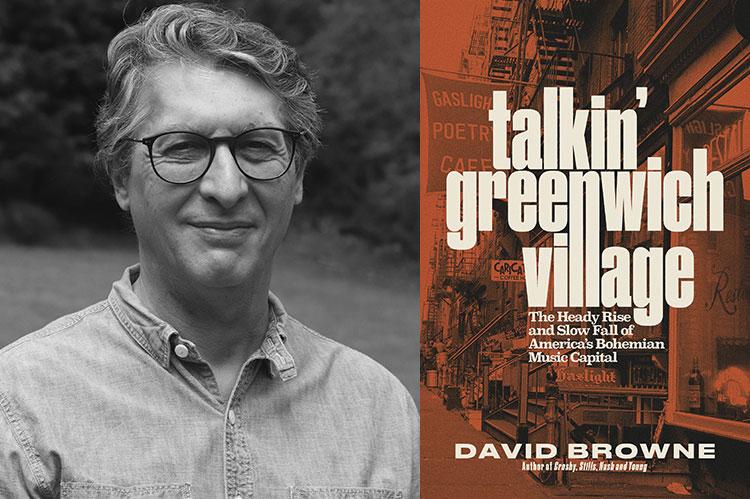

“Talkin’ Greenwich Village”

David Browne

Hachette, $32.50

When I was a newly minted resident of Greenwich Village/young hopeful musician in the summer of 1993 I had a ritual of waking up from a late night, rolling out and taking a coffee a few blocks down to Washington Square Park, where I would lounge languidly in the fountain and let the sun slowly reanimate me back into some kind of human form.

My band had a weekly Wednesday residency at a place called Nevada Smiths in the East Village on Third Avenue, not a cool music venue, but more of a brightly lit college bar with a makeshift stage and a crappy sound system that catered to N.Y.U. students. We used the gig to have something regular to build up a following.

One of these fountain days was the afternoon after a Nevada show and I happened to be complaining to another musician I’d met about how we needed to get out of there and into proper places like CBGB when this bearded and grizzly older dude, not discernably homeless but wouldn’t bet my own premises that he had one, overhears me and says, “Cee-Bees is great but you guys missed it, man. I used to just walk right in there and see Talking Heads, the Ramones, Blondie, the Voidoids . . . rock-and-roll is dead in this town now.”

This was a different variation on a similar speech I’d heard only a few nights before from a different older guy I was talking to at the Corner Bistro in the West Village who was prattling on about his gloriously misspent youth from an even earlier time at the Fillmore East and Max’s Kansas City. “I saw the Allmans at the Fillmore, Janis, Otis Redding . . . used to catch Lou with the Velvets up at Max’s . . . not even that many people there, would just walk right in. Yeah, this town used to be great but it’s over,” he proclaimed.

Everyone’s era was the best and you always “missed it.”

Back to the fountain. As Grizzly Adams kept preaching “his New York” to me, ad nauseam, this old street comedian named Albert Owens, who I’d sometimes catch as I was stretched out sunbathing, started performing standup. He was perched on the grill in the center part of the structure where, when functional, the water would spout up, telling jokes and carnival barking to conjure up a crowd.

Then he did something I never saw him do. To his left stood a very young, wide-eyed, and fresh-faced young man Albert seemed to be mentoring. He brought him on, saying, “This is one funny dude, met him in one of the clubs the other night, but he’s new to this game and to the park so make him feel welcome, but if he bombs it ain’t awn me . . . ladies and gentlemen, Dave Chappelle!”

On he came, a then-unknown Chappelle, and I could tell he was bitingly funny but it was the middle of a weekday and there was very little crowd for him to engage and the ones who were there didn’t seem up for having comedy foisted upon them as they ate their lunch, so nobody really latched. Frustrated, he quipped, “ ’Bout the best thing that could happen to me right now is this fountain comes on. What the hell happened? Didn’t y’all used to be down here beatin’ drums, singin’ and carryin’ on, changin’ the world and shit? Y’all got soft.”

He was, of course, harkening to the bygone days of the park, starting in the late ’50s with the big Sunday folk jam sing-ins and referencing the infamous “beatnik riot” in April of 1961, when the city, in denying a permit to the park musicians and singers, set off a free-speech protest that many cite as one of the starter pistols to organized upheaval, a trademark of 1960s activism.

The significance of this incident and all the incredible eras of downtown New York City music, their visionary progenitors (both the artists and venue owners), and the wild evolution of the ever-changing landscape therein is thoroughly explored in an enlightening new book, “Talkin’ Greenwich Village: The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America’s Bohemian Capital” by David Browne.

Mr. Browne, a senior writer at Rolling Stone magazine, synthesizes his extensive research seamlessly, propelling the story forward like a good historian, but has the added skill set of a seasoned music journalist. Also, having been a longtime Greenwich Village resident, he has a palpable love of subject, giving the text an added degree of warmth. As a result, the fun facts are many, the stories are enriching and colorful, and the historical perspective puts forth a portrait of how the music culture was ignited, changed, and pushed forward exponentially by the artists who sprung up in early-to-mid-’60s Greenwich Village. He then continues to document the scene and its subjects past its peak, up to the year 1986, ending with the emergence of the non-folkie yet poignant singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega.

No man ever steps in the same river twice. We all know that to mean that time marches on, bringing with it changes for both the man and the river, but what if the man never steps out of the river and refuses to change as the river rolls? That is what you have in the most dynamic figure in the book, and the vehicle that Mr. Browne chooses to tell the musical tale of Greenwich Village through, the larger than life and reputed “Mayor of MacDougal Street” ragtime-picker/blues-brayer Dave Van Ronk. Despite the drastic changes in surroundings and the public’s always morphing musical taste, Van Ronk continued to play shows as a strident folk purist till the time of his death in 2002.

Dylan is the big bang, the unmoved mover, the immortal bard — whatever handle you want to pin on him he’s deserving of it all. He literally influenced everything in music that came after him, but as you find out in the book, when he hit town in ’61 he was just scratching his way through Woody Guthrie covers and fumbling forward toward actualization.

Van Ronk was one of the original flagbearers of the movement, an alpha on the scene, mentor and guitar teacher to many of the soon-to-be-name performers, and very much the John the Baptist to Dylan’s Jesus, even letting him crash on his couch when he first hit town.

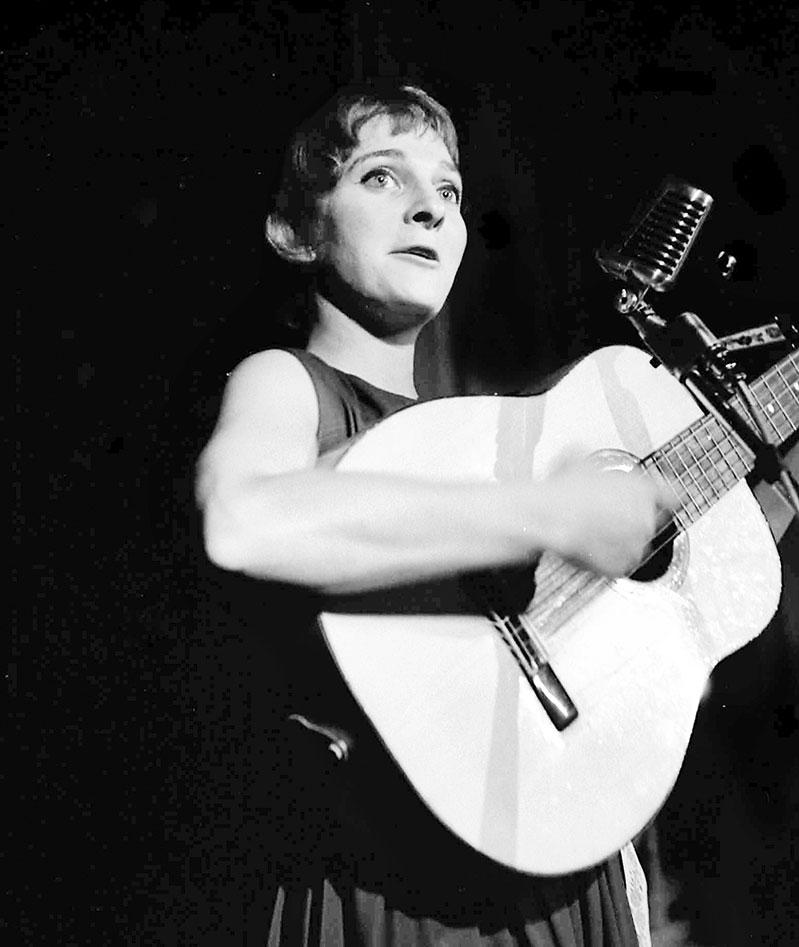

Courtesy of Irwin Gooen Collection

There is a lot of good Bob stuff to chew on here, including stories of late nights when he and Van Ronk would hold court and argue the topics of the day at the original Kettle of Fish bar on MacDougal Street. All the usual suspects associated with the scene — Tom Paxton, Phil Ochs, Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Judy Collins, and many other notables — would be on hand to witness and participate in these discussions, many of whom are still alive and give scintillating accounts of these gatherings.

Mr. Browne also unfurls insightful business back stories about the venues that nurtured Dylan and the rest. Not surprisingly, the New York mob shows up to make itself known with more than a few shakedowns. Hallowed halls of yesteryear such as the Gaslight Cafe, Gerde’s Folk City, the Five Spot, Cafe Au Go Go, the Village Gate, the Night Owl, and many more are chronicled, along with enduring stalwarts such as the Bitter End and the Village Vanguard.

I will confess to being the bull’s-eye audience for something like this. I am a fervent Dylan fan and a longtime New York City musician. I played my first-ever Manhattan show at the Bitter End in the summer of 1986 (I still perform there), and I make a good portion of my living gigging in Greenwich Village to this day, so I might be a little biased, but the deepening of my knowledge of those storied streets via this book feels like a blessing.

Back in August I was on a break standing in front of my gig on East Fourth Street and overheard a couple of dudes in their late 20s revving up about the recently announced Oasis reunion tour. They were scrolling their phones and grumbling about the expense of the tickets. I said, “Me and my buds saw Oasis for next to nothing at their first-ever U.S. show back in the ’90s at the Wetlands.”

One of them perked up and said, “Whoa! I woulda killed to see ’em back then. What the hell is the Wetlands?”

I said casually, “It was a really cool little hippie rock club down by the Holland Tunnel. Long gone now but it was great. Yeah, they were playing, wailing away, wasn’t even packed, we just walked right in. You guys missed it.”

And on it goes . . .

Christopher John Campion, a singer-songwriter and regular visitor to Amagansett, is the author of “Escape From Bellevue: A Dive Bar Odyssey,” published by Penguin-Gotham.

David Browne lives part time on Shelter Island.