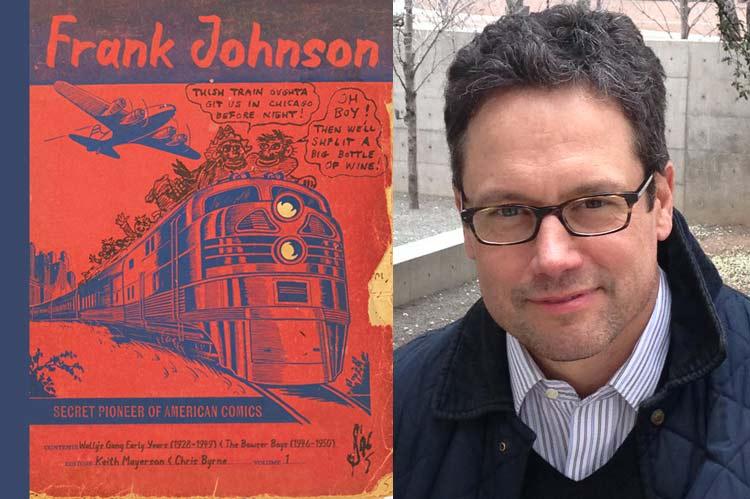

“Frank Johnson: Secret Pioneer of American Comics”

Chris Byrne and Keith Mayerson, Editors

Fantagraphics, $49.99

Welcome to "Wally's Gang," a series of stories drawn in comic form akin to contemporary graphic novels but originating before that form appeared on the publishing scene. And for the kicker: "Wally's Gang" was never shown or shared over the 50-year span (1928-1979) of its creation.

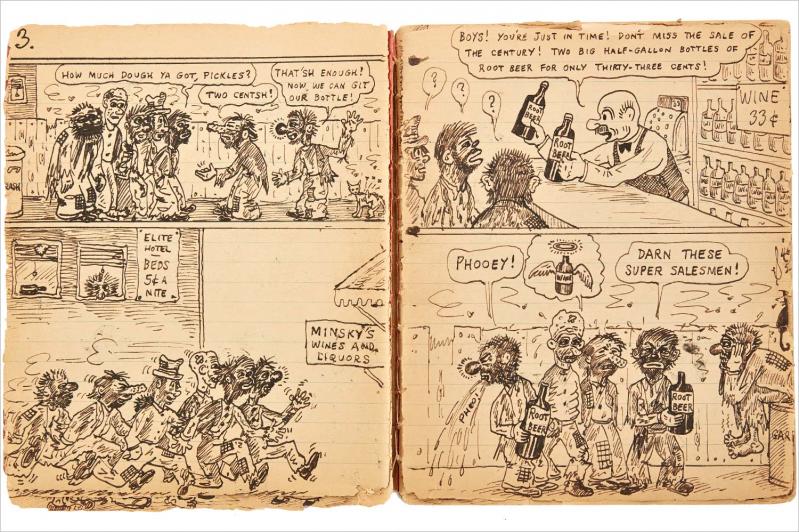

Frank Johnson, a man with no formal training in art, drew these comics in lined composition notebooks using graphite pencil, and, as Chris Byrne, co-editor of the volume, writes, "His entire body of work — which includes more than 2,300 pages of images in notebooks as well as 131 unbound drawings — was discovered by his family posthumously."

Front matter that orients readers with well-informed historical context sets the stage. In a foreword, Byrne offers the known biographical information (it is scant) about Johnson and reveals the series of introductions and collaborations among collectors, editors, and curators that led to the current volume (a planned second volume to present the remainder of Johnson's oeuvre is mentioned).

In an introduction, Keith Mayerson, the other co-editor, calls attention to the uniqueness of Johnson's work, and contextualizes its unpublished status during the artist's lifetime:

"In terms of its form and composition, Johnson's work is a prescient epiphany. It wasn't until the late 20th century that printing technology could faithfully and inexpensively reproduce pencil lines and tonal values. Formally, Johnson's work represents the first fully rendered graphite comics, predating the 21st-century wave of pencil works and earlier colored-pencil artists such as Raymond Briggs. Publishing (and now online) innovations that allowed for half-tones and shading to be faithfully reproduced didn't happen in America until well into the 1980s."

The word "trove" comes to mind, complete with a sense of the mystery of this virgin excavation. One finds a similar sense of wonder in the story of Emily Dickinson's 1,000-plus unpublished poems that were discovered after her death in the "fascicles" (hand-sewn books) she had created — though Dickinson, unlike Frank Johnson, did share, if not publish, many other poems during her lifetime.

The titular character of "Wally's Gang" is Wally Reading, a self-aggrandizing grump whose catchphrase — "BAH!" — registers his frequent irritation. Yet Wally is the glue to the gang, made up of six men who are members of Wally's club. They live in the clubhouse, cook up schemes together, and react as a group to life's events.

Although lots of jostling and competition among the men unrolls, a sense of gentle camaraderie prevails. It's a common-man bachelor utopia, where no one ever falls too hard and foibles are forgiven. Antics, harebrained schemes, and madcap storylines show the men's characters, each drawn with adroit recognizability. Frank Johnson was as skillful as a voice actor performing multiple roles and nailing them all every time. Story arcs within the larger, longer whole conclude with one-liner wiseacre cracks, plays on words, and other punchlines.

After spending some time with "Wally's Gang," we begin to catch the drift of how conclusion flows from setup. A sense of logic, which is predictable, arises, though it is more satisfying than pat. Generally, the members of the gang are striving for solutions to ridiculous problems, often of their own making or compounded by their witlessness (e.g., an attractive doctor, who is a woman, moves in nearby and the gang starts self-inflicting injuries to draw her to the clubhouse). The men in the gang are not necessarily well behaved, but they are unaware, innocent. The absurdity of life is revealed by the obliviousness of the pure of heart.

This book is lovingly published by Fantagraphics, the 40-plus-year-old independent publisher of comics and graphic novels that has helped define the field. A gracious, roomy design with a generous trim size supports the clarity of the comics themselves. The editors and publisher of this book have taken its publication seriously as a resource for others. Artists, readers, curators, and scholars — and those with a combination of overlapping roles — will find a carefully presented volume.

High production values place the book on the expensive side; libraries should consider it as a first purchase for all collections where comics and graphic novels are popular, and where art, art history, and cultural history are of interest to the community. Or how about everywhere? Because books like this help us shape an understanding of these enriching subjects.

The volume faithfully, even somewhat fetishistically, reproduces the source material in full, capturing the faint blue lines of the composition books in which the comics were drawn, the scans framed to include the piled accumulation of pages on the left edge as the comics progress.

There is a sense of viewing archival material, including the front and back covers of each of the composition books that house Frank Johnson's creations, the first nine of which are included in this publication. The color schemes, graphics, and printed names of the manufacturer on the covers of the notebooks (Red Robin, Highest 100 Per Cent Composition Book, Penworthy, Whitefield, Victory Du-O-Stitch) highlight the aesthetic of the era of the work.

Johnson placed the names and numbers of his volumes right on the front of the composition books, somehow both ignoring and integrating the manufacturers' existing designs of the notebook covers in a quirky display of D.I.Y. prowess.

An understanding of the origins, discovery, and championing of these comics, together with the experience of reading them, generates robust lines of inquiry around creativity and how our culture perceives it and greets it. If we accept the expert and enthusiastic framing by the editors of the volume, including discussions of Outsider Art, or Visionary Art, Frank Johnson's work gives us new evidence to consider.

What other valuable, even brilliant, creative productions are we not seeing, reading, hearing, experiencing? To what extent is the very nature of what we have access to tied to the drive (on the part of the creator) to share the creation, or to the drive of ambition or desire for recognition? How does the recognition of others influence the making process? And the absence of recognition? In our contemporary climate of hyper-sharing, where there are many forms of celebrity on a local to a global scale, it may be even less possible to consider acts of creativity uninfluenced by the lure of recognition.

There's a sense of destiny in reading Frank Johnson's comics. Technology has now rendered the works publishable; they seem meant to be shared. Yet he was doing it with the gusto of not knowing. Like a kid who can't ride the bike yet, but is, actually, riding the bike! How wonderfully fine that he was willing to pedal off into the sunset, and keep pedaling for 50 years, without any praise, without any affirmation of his feat.

Evan Harris co-created the zine Quitter Quarterly. Her other zines and comics include Occasional Alphabet, SuperHeart, and the Cosmic Rock booklets. She lives in East Hampton.

Chris Byrne is the owner and founder of the Elaine de Kooning House art center in East Hampton.