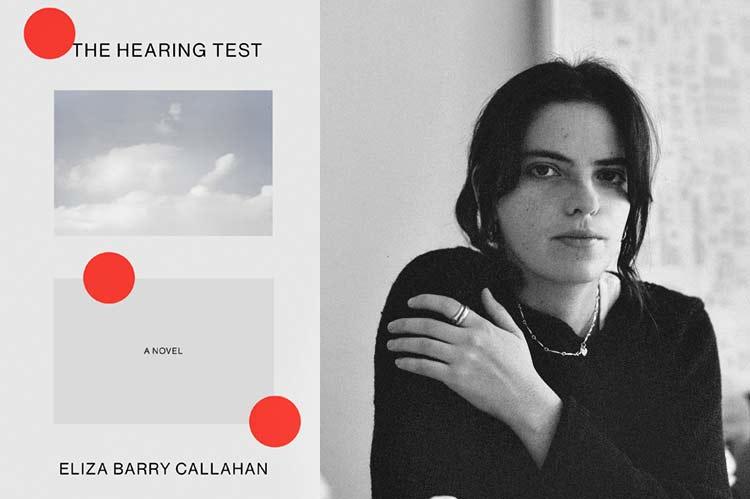

“The Hearing Test”

Eliza Barry Callahan

Catapult, $24

Early one morning an artist awakens perplexed by what she describes as a “deep drone in her right ear accompanied by a sound I can best compare to a large piece of sheet metal being rocked, a perpetually rolling thunder. I moved from the bedroom to the living room in a controlled panic.”

Rather than fly to an intimate wedding reception in Venice, she finds herself in an emergency room. A doctor studies the scans and X-rays then looks into her eyes and says: “Bad luck.”

“The Hearing Test” is a novel by turns wry and revelatory and taut. “I had been struck by Sudden Deafness,” the narrator discovers as she begins her pilgrimage to find out both cause and cure. To her, the term Sudden Deafness “sounded so severe that it verged on comedic for the wingspan of one moment.”

That rolling thunder sound meant her brain was trying to replace lost frequencies. “Each specialist relayed that I was unlikely to make a full recovery, or any recovery at all — worse, one said, it could mean the onset of a degenerative hearing disease that typically affects people late in life and concludes in a profound deafness. The sincerest strain of quiet.”

As Eliza Barry Callahan explores the strains and profundities of Sudden Deafness through her narrator, the quest is often met with frustration. Proposed “cures” often sound barbaric. “We can get to the moon, [one] doctor said, but we can’t get to the inner ear.”

After a time, most friends and family stop checking on the narrator’s hearing loss, except for one friend and her own mother, who outright announced that she’d rather die than become deaf. Nonetheless, she keeps a journal of her experiences, her perceptions, her experiments. Alone, she speaks to herself out loud.

What hearing remained? One phenomenologist posited that there is a “tiny rip” that “somehow separates you from yourself in the moment of hearing yourself speak.” She could hear “her eyelids meeting — dull and dense like a head hitting a pillow.” She mocks herself for feeling angry with her upstairs neighbors for jumping rope at 10 p.m. on Sundays. Only to realize when she turned off her own dishwashing water that they weren’t stomping on the floor. She was hearing the sound of her own heartbeat.

The narrator doesn’t shy away from the peculiarities of those who claim they can restore her hearing. When the main character meets with a hypnotist, she notes that she “had begun to understand my own life by misinterpreting things I was reading and experiencing with only half of my attention.” Onscreen the narrator sees the hypnotist’s rescue macaw, which has no voice box, thus lacking a natural defense.

“The following day, [the hypnotist and I] met again — this time thirty minutes later. The sun had already begun to set and the hypnotherapist was just a solid dark mass. Could I see him, or was he sitting dangerously close to his own shadow? . . . He added that he didn’t usually hold sessions at this time of day and that perhaps he should invest in a window treatment. . . . He apologized profusely for the poor connection and now this. I told him I was used to poor connections.”

“He said it was funny that I mentioned poor connections.”

The hypnotist goes on to discuss buzzer tones, some of which emanate from a “radio station no one claims to run.” All this from the person who claims he will help her regain her sense of hearing.

And then there was the doctor who had likened the difficulty of understanding the complexities of the inner ear to lunar space travel. He had “recommended abstaining from anything that might give way to heightened emotions, from weddings to surprise celebrations, unexpected deaths to orgasms.” He went on to ask whether the narrator had experienced “a heightened moment” before the hearing dropped.

Of course this novel is replete with crystalline heightened moments, moments very few would savor as “heightened.” Yet when one sense is diminished, others often become all the more heightened, all the more important.

Lou Ann Walker, executive editor of TSR: The Southampton Review, teaches creative writing and literature at Stony Brook University.

Eliza Barry Callahan lives part time in Sag Harbor.