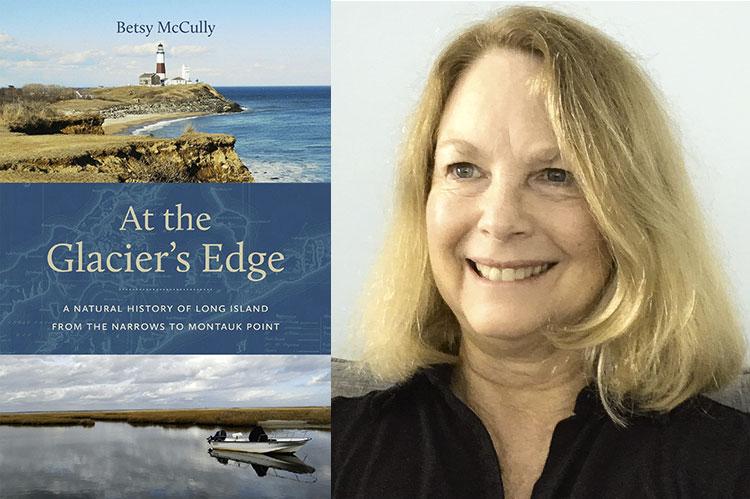

“At the Glacier's Edge”

Betsy McCully

Rutgers University Press, $27.95

Betsy McCully sure can write about nature. Her latest book, “At the Glacier’s Edge,” is brimming with beautiful descriptions of Long Island’s beaches, marshes, lakes, rivers, grasslands, and woods. She offers precise details in fresh language as she shares historical, scientific, and personal accounts of these places. She synthesizes careful research and insightful reflections with her own observations. Gorgeous photos also taken by the author accompany her written descriptions.

Together, Ms. McCully’s text and images create a compelling invitation to readers to get out and explore and a powerful call to action to “preserve and restore” these endangered places on Long Island, which, as she notes in her introduction, is her aim.

I want her to aim for more, to gesture beyond romantic ideals of human relationships with nature and individual solutions to environmental problems, to situate her work in relationship to emerging critical perspectives on conventional natural history, and to reckon with the politics of environmental justice more fully.

In her opening lines, Ms. McCully’s compelling prose sets the bar high: “On a winter’s day I stand at the bluff’s edge, cold wind buffering my body, waves fifty feet below breaking on the narrow beach. Montauk Point is a wave-washed, windswept place at land’s end, where North America’s eastern flank slopes beneath the Atlantic and falls off into sunless depths. Beneath the low clouds, cobalt-blue sea is slivered in patches where shafts of sunlight break through.”

In this passage, the present tense, the sonic impact of her alliteration, and the energy of her verb choices all brought me into the scene with her. Throughout the book, she maintains this level of careful writing, demonstrating her attention to and love for these places she describes, bringing them to life so readers feel a kinship with them. I especially loved when she described some of my favorite places, like the Walking Dunes and Shadmoor State Park. I was also inspired by her to explore new places, like Fire Island, Lake Ronkonkoma, and the Peconic River.

Betsy McCully Photo

To support her claims that important ecosystems on Long Island are in jeopardy and her call to action, Ms. McCully shares reams of research from a range of reliable sources about the past damage, current harm, and looming future threats caused by human-generated development, climate change, and misguided efforts at remediation. She draws upon the work of canonical environmental writers such as Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold, who have made important contributions to the contemporary environmental movement and environmental ethics.

But her choices about the scope of her work, the types of environmental degradation to emphasize, and the authors she uses to contextualize her work omit important ways of thinking about ecology and of addressing environmental concerns. In particular, she ignores the racialization of access to the outdoors, environmental degradation, and safety, she overlooks the solutions being employed in native communities, and she excludes a vast literature of nature writing from writers such as bell hooks, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Camille T. Dungy, and others whose concepts of nature and ecology differ from white, Western conventions.

J. Drew Lanham’s classic 2016 essay “Birding While Black” contributes an essential perspective for a full understanding of the promise and perils of the outdoors as an avenue to environmental preservation. In it, he recounts his experiences as a Black man engaging in birding, an activity that takes him to a range of places like those that Ms. McCully wants readers to explore, spaces that Mr. Lanham experiences differently because of his skin color and racism. In these spaces, he encounters Confederate flags, K.K.K. graffiti, and white people who want to keep Black people out. Yet he persists in birding himself and calls for more people of color to get out into wilder places.

Much like Ms. MuCully, he hopes that “As young people of color reconnect with what so many of their ancestors knew — that our connections to the land run deep, like the taproots of mighty oaks; that the land renews and sustains us — maybe things will begin to change.” But his call is inflected by his understanding of racism.

In addition to navigating discrimination and safety concerns when outdoors, many Black, Latino, and Asian people have less access to “forests, streams, wetlands, and other natural places” than white people do, according to Conservation Science Partners. Thus, Ms. McCully’s call for readers to explore the outdoors may be taken up differently by those who are less safe in the outdoors and those who have less access to it.

To address the crisis that Ms. McCully so dutifully documents and to preserve the spaces she so eloquently evokes, we need to employ more capacious definitions of our neighbors, we need to pay more attention to all of our neighbors, and we need to look beyond Western notions of nature and individualism. Some important solutions to environmental degradation can be found in Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), which, as the Environmental Protection Agency explains, “is the accumulated knowledge American Indians and Native Alaskans have about their environment. It’s important for scientific research, but is threatened by environmental change.”

On Long Island, members of the Shinnecock Nation are drawing upon TEK to protect beaches from coastal erosion. The Montaukett Tribe is working to preserve their Algonquin language and Indigenous cooking practices. Ms. McCully could use her considerable talents to document these and other similar efforts, which would provide a more accurate understanding of the natural history of Long Island and a more viable path to a shared future.

Stephanie Wade teaches writing at Stony Brook University. She divides her time between East Hampton and Belfast, Me.

Betsy McCully is the author of “City at the Water’s Edge: A Natural History of New York.” She lives in East Hampton.