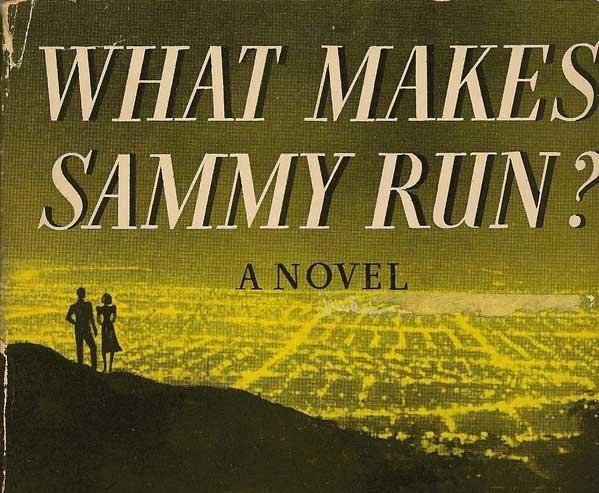

I can’t believe I waited this long to read Budd Schulberg’s “What Makes Sammy Run?”

Schulberg: a prince of Hollywood, as he was called in the subtitle of his memoir, “Moving Pictures.” He was the son of the production chief at Paramount, and, I might add, a lord of Quiogue in his later years — for a long time the sole noteworthy thing about that obscure little hamlet. A Catholic church cheek by jowl with a Presbyterian one, a corral with a couple of horses across the way, some water twinkling through the trees, and then there was Budd.

I’ve seen “On the Waterfront,” of course (credit: screenwriter), back when I had time to watch black-and-white movies (that would be the 1980s). And the legendary “A Face in the Crowd,” with a raging Andy Griffith, of all people, has been at the top of my list ever since then, but I came to Schulberg’s non-screen writing as a low-grade fight fan, through his pungent 2006 collection “Ringside: A Treasury of Boxing Reportage,” from the Chicago publisher Ivan R. Dee. Well worth perusing.

But I’ve got this small shelf of Hollywood novels, on the dream gone sour. Dan Wakefield’s “Selling Out” is a fun one. John O’Hara’s “The Big Laugh,” semi-famously praised by Fran Lebowitz as the greatest Hollywood novel ever written (I’d now say second greatest), stars Hubie Ward, an actor with a theater background who probably out-heels Schulberg’s Sammy Glick, he just doesn’t reach the same dubious heights.

And then there’s an overlooked classic, a collection that reads like a novel, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Pat Hobby Stories,” which first appeared in Esquire in 1940 and ’41. Contemporary with “Sammy,” they cover some of the same territory, maybe even more successfully getting at the loserish side of the glitter, the politics of the commissary, the hangers-on, the sleights — not unlike the old story of the big-shot producer calling a screenwriter into his office, telling him to have a seat, and the chair collapses under him like matchsticks just for chuckles. You know where you stand, copy boy.

So, Sammy Glick, up by force of will and cunning from the mean streets and tenements of the Lower East Side to head a major studio, is the ultimate striver, stealing ideas if not whole scripts, sparing no shoe leather to the face of those he climbs over, devoid of an ounce of empathy. Through it all, he remains something of a sympathetic figure, but what’s funny is that the character later came to be seen as a kind of exemplar of all-American individualism and self-betterment.

Which appalled Schulberg, as is clear in an afterword he wrote for a 1990 edition, in which he makes plain his disgust at society’s me-me-me turn. “And if that’s the way they go on reading it,” he says, “marching behind the flag of Sammy Glick, with a big dollar sign in the square where the stars used to be, the twentieth-century version of Sammy is going to look like an Eagle Scout compared to the twenty-first.”

This is me, mopping my brow.