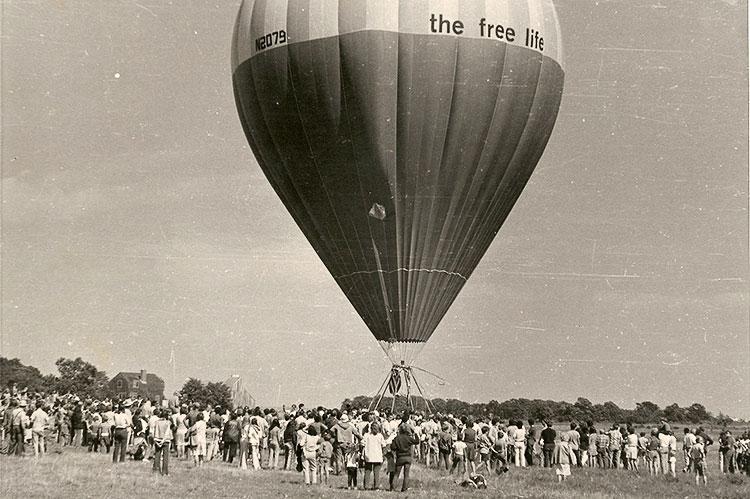

Fifty years ago, Sept. 20, 1970, saw a colorful, seven-story-tall balloon about to embark from a field in Springs on a flight across the Atlantic Ocean. If it succeeded it would be the first such attempt to do so.

Robert Alan Arthur, screenwriter and resident of Springs, wrote in Esquire a year later:

“On the one hand you had to be in awe of someone determined to set a world record, no one having flown a balloon across the Atlantic before. That balloon hanging over George Sid Miller's field was some beautiful sight. And though the attempt failed, the three adventurers lost forever, the balloon did take off. I was there. I saw it happen. And take it from me that balloon flight was the most bizarre event I've ever witnessed in this town.”

In the ballooning world, the flight of the Free Life is still a subject of debate, and in East Hampton it has entered the annals of local lore as one of the most remarkable and unforgettable events of our town. In the near-anachronistic world of derring-do, here were three young, attractive, and personable champions of adventure attempting the seemingly impossible. And it was thrilling.

For Rod Anderson, age 32, it was a crazy, intriguing idea that he had by virtue of tireless persistence nurtured for four years into reality. Through setbacks and the ever-nagging lack of funds, he kept at it, and then, in the summer of 1970, he found himself with a full-on working Roziere-type balloon capable of lifting his pilot, himself, and his wife aloft in an 8-by-8-foot gondola kitted out with navigational equipment, food, and cameras.

For Malcolm Brighton, also 32, this was a ready-made chance to make history. As a professional and experienced balloonist, no one was more aware of the challenge of the Atlantic crossing. An Englishman, he was widely known in the European ballooning world as a designer of lighter-than-air conveyances for films and commercial exploits. He had worked on his own designs for a trans-Atlantic flight, but they were still very much on the drawing board.

Now here was presented to him a fully equipped, ready-to-sail craft. He arrived from England in the hamlet of Springs, spent a week studying the project, and, though he felt he could have done it better, readily accepted Rod's offer to be the pilot.

For Pamela Brown, 28, the idea of flying across the Atlantic in a balloon seemed a crazy notion, to say the least, but that was exactly what captured her imagination. From a prominent Kentucky political family, her ambitions were theatrical, with a long list of summer stock and television commercials already on her resume. What could be more theatrical than flying across the Atlantic in a balloon with her beloved husband? She would be the filmmaker and chronicler of the trip.

The day of the flight was a perfect, cloudless September day. The farm field, normally a pasture for a few horses, was filled with excited people arriving while it was still dark to witness the inflation of the seven-story balloon. The international press was there, and TV cameras were set in place atop impressive network vans. At noon the desired northeasterly wind arrived, and Malcolm began the countdown to launch. Flags were unfurled, champagne uncorked, Pam set her camera to rolling while volunteers held tight to the rigging.

The Free Life was finally let loose of its tethers, the Springs volunteer ground crew pinned to the sides of the gondola as the giant inflatable capable of lifting hundreds of pounds skimmed across the meadow. Then came Malcolm's final words through the megaphone, “Let go!” With that, the immense and colorful balloon lifted off the ground and elegantly sailed up into the sky and out over the water.

The aeronauts were on their way, and it was magical. For one brief moment, time and reason were suspended, and it was as if those of us on the ground were lifted up into the blue sky along with them. Some 30 hours later, the Free Life went down in a storm 500 miles from land. No trace of the balloon or its crew was ever found.

This of course is only a brief view of my friends and their venture, and one perhaps seen through the eyes of an undaunted loyalist. Much has happened in the 50 years since. For one thing, the pioneering attempt by the Free Life inspired many more attempts in the following years. Success came in 1978 in a helium balloon named the Double Eagle with three crew aboard landing in France to enormous media applause. Richard Branson made it across in a hot-air balloon in 1987.

Now there are balloon races across the Atlantic, and next year a trans-Atlantic attempt with the first woman pilot will take place. And yet there is something about the particular story of the Free Life that has captured our attention for 50 years.

A documentary film, premiered at Guild Hall in 1972, chronicled the launch and the weeks afterward as hope dimmed for any rescue. In 1995, a friend of Malcolm's, the noted journalist, explorer, and lighter-than-air enthusiast Anthony Smith, wrote a book titled “The Free Life: The Spirit of Courage, Folly and Obsession.” Asking why people make such attempts, he brought insights to this story via his own exploits and adventures. Peter Matthiessen wrote about it in his book “The Snow Leopard,” Ralph Carpentier painted it, poems have been penned, psychics have weighed in, and in 2015 over 80 people gathered in Ashawagh Hall for the 45th anniversary with their memories of that extraordinary day.

There are few of us left — friends, family, ground crew — who actually knew Pam and Rod and Malcolm well, and we vividly remember how engaging they were, full of life and high spirits. Malcolm's daughter, only 8 when he died, is actively involved in creating a website about the Free Life. Anthony Smith died in 2014 at age 88. At 85, he had built and then voyaged across the Atlantic Ocean on a single-sail-powered raft. On CNN, a reporter, Pamela Brown, Pam's niece and namesake, is a talented reminder of her adventuring aunt. And here in Springs, to mark the 50th anniversary, I am working with the Springs Historical Society on mounting a plaque on Fireplace Road next to the launch field.

The field itself, so perfect in 1970, with its flat bare expanse on the edge of the ocean, is now home to one rather large, imposing house and many trees that hinder the view, but on clear days, especially with the sun giving an iridescent sparkle to Accabonac Harbor, the spirit of the Free Life seems to live on.

Genie Chipps Henderson has been a resident of Springs for 40 years. She is the archivist at LTV, which on Sunday at 5 p.m. will air a special about the Free Life, and the author of the novel “A Day Like Any Other: The Great Hamptons Hurricane of 1938,” published in 2018 by Pushcart Press.