The best thing about growing up in the same house in Queens with my grandparents, besides the 5 bucks Grandma would stuff in my hand, was the frequency with which I could stop downstairs and grab a bowl of fresh pasta fagioli or that shot of vermouth Grandpa would sneak to me.

I was 10.

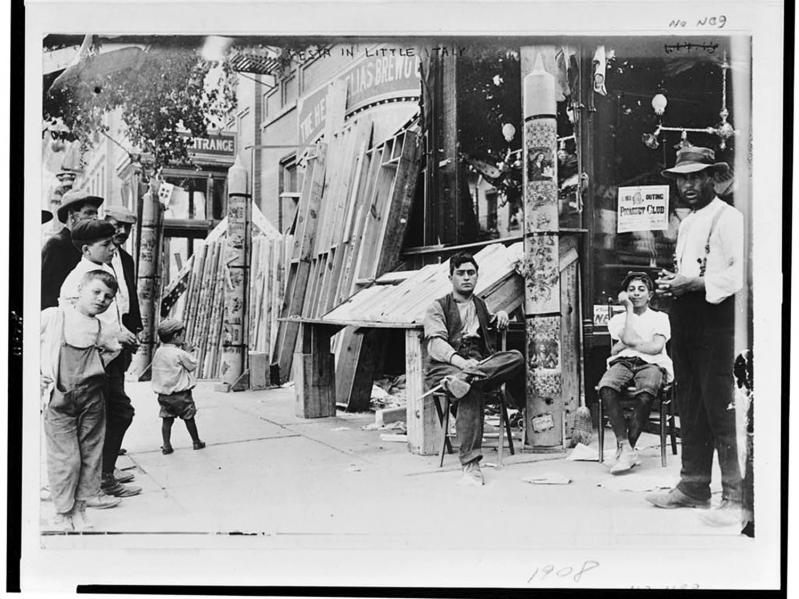

Sitting at their lime green, metal oval table, with the dusty Tiffany lamp hanging above, straight out of a 1950s TV show, my grandfather, an immigrant from Potenza, Italy, would reveal himself as a storyteller like no one I ever met, story after story after story, some more fascinating than the last, stories of walking along Mulberry Street in 1910. I could smell the frying sausage and peppers in the street as he weaved his tales.

“How was the boat ride from Italy, Grandpa?”

“It was so crowded,” he said. “Sending me to America was my mother and father’s dream, and I was the first of many.”

Grandpa was a short man, a little over 5 feet, a few strands of white hair on his bald head, but at 92 as spry as ever, never missing a beat. He wore gold-rimmed glasses that never sat straight on his face, and the pack of De Nobili cigars in the pocket of his gray flannel shirt hadn’t been smoked in 20 years, but still a fixture.

The week before Christmas it was always a somber, more reserved Grandpa, one I was sad to see, as he always told me a story of his becoming a waiter in Little Italy, befriending the piano player, staying late to share uneaten dinners.

“We were both poor, Frankie, really poor.”

And so, his story about his early life unraveled as if in real time.

“Take my hand, let’s take a trip back.”

And for the next hour, I was transported back to where round clocks on poles decorated every street, and people traveled around Manhattan on horse and buggy on streets of dirt and rocks.

“How old were you when you arrived in America?”

“I was 14 and didn’t know a word of English, staying with an uncle on East 12th Street.”

“Did you get a job?”

“When I was 17, I got a job in Little Italy as a waiter, cleaner, everything to make money. I worked from 9 a.m. to midnight every day.”

“Wow, that was a lot of hours”

“Me and Izzy.”

“Who was Izzy?”

“The piano player in the restaurant I worked at. We became really good friends, staying late to sneak a few drinks when the place closed, then we’d sit around laughing at all the ‘cokies.’ ”

“The cokies?”

“A bunch of the workers used this white powder they’d sniff up their noses. Me and Izzy never did that stuff.”

“That doesn’t sound good.”

“We always ended the night with him playing a few songs on the piano. Fantastic memories.”

“Did you save the money?”

“All the money I made I sent back to my mother and father in Italy, until they arrived years later, after I got married to your grandmother.”

“Sounds like a simpler time, right, Grandpa?”

“Much simpler,” he said, smiling as though he were 20 and not 92 years of age.

“Whatever happened to Izzy?”

His eyes teared up whenever I asked about Izzy.

“After I got married, I bought a taxicab and stopped working in the restaurant, losing touch with him. To this day, I think of him often, my first friend in America, bonding like brothers, two guys from two different worlds, but I loved him for accepting me as one of the guys. He was my first, true American friend. I never wanted to go back to Italy after we met.”

“Ever think about reaching out to him?”

“Maybe one day, Frankie, maybe one day,” he said with tears filling his eyes.

Grandpa’s Christmas stories continued until he passed away at 98, my 92-year-old grandmother finding him in his bed.

The next week, at the funeral parlor in Astoria, I sat next to Grandma, reflecting on Grandpa’s wonderful life, his sense of humor and vivid stories.

“He loved telling you his stories, Frankie, you were his biggest fan,” she said. “You really brought him back to his childhood in Little Italy.”

“I loved his Christmas story, the one about Izzy.”

“Izzy was your grandfather’s first friend in America, real buddies, always talked about him, hoping they’d one day get back together.”

“I also remember Grandpa always cried when a certain Christmas song played on TV or the radio.”

“ ‘White Christmas’?”

“Yeah, that’s the one! He always cried when it played.”

“That was Izzy’s song.”

“The piano player wrote a song?”

“Oh, his real name was Isidore.”

“Isidore?” I asked.

“You may know him by his other name, Irving Berlin.”

Frank Vespe, a “Guestwords” contributor for many years, lives in Springs.