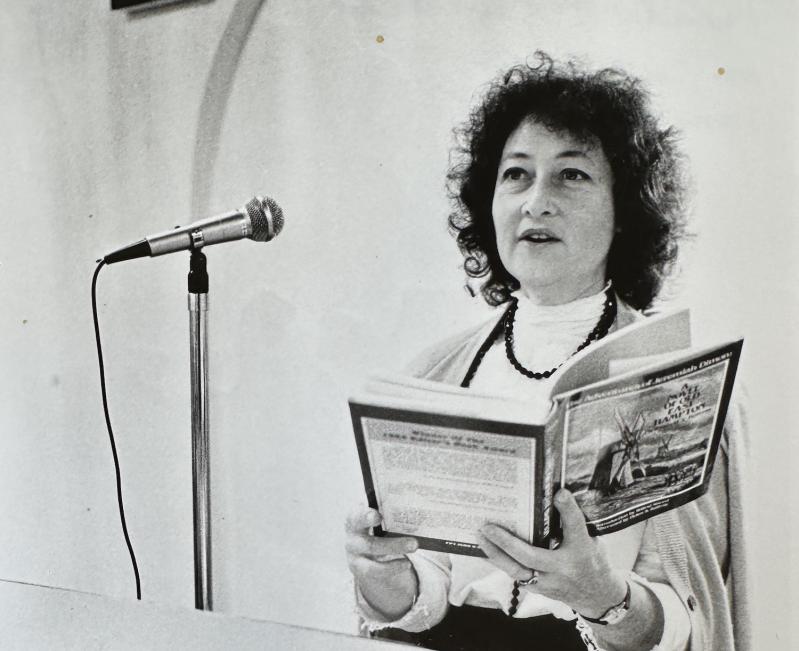

Helen S. Rattray may have stood only 5-foot-1 in her prime, but she was a towering figure in the newsroom and in the town her paper served. A consummate journalist, exacting editor, and dedicated champion of the free press, Ms. Rattray served as publisher of The East Hampton Star until her death on April 16 and was its editor in chief from 1980 until 2003, when her eldest son, David E. Rattray, took over that role.

Ms. Rattray, who was 90, died of septic shock and cardiac insufficiency three days after being admitted to Stony Brook Eastern Long Island Hospital in Greenport. She had dementia and had been in declining health for the past six years.

A woman of strong opinions with an abiding sense of the responsibility that came with running a community newspaper, Ms. Rattray was not one to balk at conflicts, and over the years that she ran The East Hampton Star she faced down many.

"She was as feisty as they come," said David Rattray.

She kept regular office hours until 2019, and even in the early days of the pandemic continued to attend editorial meetings via Zoom.

Continuing the tradition of strong and independent journalism upheld by her late husband, Everett T. Rattray, before her and his mother, Jeannette E. Rattray, before that, Ms. Rattray steered The Star with a firm hand and unwavering dedication, earning it a reputation as one of the best weekly newspapers in the country. She trained journalists that would go on to work for such outlets as The New York Times, NPR, The Baltimore Sun, and National Fisherman, expecting from her staff a level of excellence on par with that found in any of those publications.

"She knew that news consumers here were by and large sophisticated readers, and you couldn't cut corners on reporting and expect them to respect the paper," David Rattray said.

"You don't have to join me in thinking that The Star is among the best weeklies in the country, but at a minimum everyone must recognize our commitment to fairness," she wrote in a memo to all departments just before the Thanksgiving holiday in 2000. "The paper is loved by some and respected by almost everyone else, including those who don't agree with our policies and opinions. Over the years I have taken a lot of heat and stood firm in the face of threats. I have taken responsibility for others' mistakes. Certainly, all of us make them, including me. . . ."

Ms. Rattray was an intensely engaged, hands-on manager, whether on the production, business, personnel, or, in particular, editorial side of The Star. As Irene Silverman, a longtime editor at the paper recalled this week, "she preferred to relay her thoughts in memos rather than confrontations. . . . Years ago, probably at a Christmas party, a few staffers compared notes and were amused to find that all of them had preserved her memos."

With young journalists just out of college or journalism school, Ms. Rattray was kind and approachable but firm. They were expected to refer to the paper's extensive style sheets and write in Star style. "It is never okay," she warned in another memo, "to put your assumptions, presumptions, into print. . . . Get acquainted with our resources, both human and in the files."

Among her numerous awards, Ms. Rattray received an honorary doctoral degree from Southampton College. With her in charge, the paper was recognized by the Linda Leibman Human Rights Fund for exemplary coverage of gay, lesbian, civil rights, and AIDS issues in 1987. She was inducted into the Long Island Press Club's hall of fame in 2017 and in 2021 was among several East End women in media to be honored by the Ellen Hermanson Foundation.

"She was used to being one of the smarter people in the room," her daughter, Bess Rattray, said. "I think she thought having high standards was normal."

"She was brave, sharp as a whip, always cleaved to the truth -- her journalistic instincts were unerring -- and was unrelenting when it came to putting out a great -- not just a good -- newspaper," Jack Graves, The Star's longtime sports editor, wrote this week.

Readers of The East Hampton Star between 1977, when Ms. Rattray's first weekly "Connections" column appeared, and 2020, when she penned her final one, got an intimate view into her life here. In her initial "Connections," she wrote of her first visit to East Hampton in 1958; in her last she took measure of her 43 years as a columnist.

"Allow me then to say I've done my best, and my ambitions have always been high," she wrote in the May 21, 2020, "Connections," announcing that she planned to begin a memoir "about the writing life."

"The column ends, but the blaze of words continues on. . . ."

Helen Hinda Seldon was born in New York City on Sept. 29, 1934, to Abraham Seldon and the former Yetta Spivack. She grew up in Bayonne, N.J., where she enjoyed singing from a young age and was a drum majorette in high school. She graduated from the New Jersey College for Women, now part of Rutgers University, went on to Teachers College at Columbia University, and was on the staff at the university's Graduate School of Journalism for two and a half years. It was there that she met Everett Rattray, who was studying in the graduate program in preparation to take over the family newspaper in East Hampton.

Their different upbringings were evident early in their courtship: His mother's family could trace its roots on the South Fork back many generations; her mother was a Jewish immigrant who kept a kosher home. Their daughter, Bess Rattray, remembers her mother sharing a funny moment from one of their early dates: "He took her out to dinner and she had lobster and wasn't sure if she was supposed to eat it with a knife and fork."

They were married in Westport, Conn., on July 22, 1960, by a justice of the peace who had been a Columbia instructor. Ms. Rattray began working at The Star just a week later.

"I think she always felt like an outsider here, from the frosty reception that she got in the 1960s," David Rattray said.

The couple built a house at Promised Land on Napeague and raised their children, David, Dan, and Bess, there. Ms. Rattray cut back her hours when they were young, but returned to The Star full time in the 1970s and became associate editor in 1976. She took over as editor in chief and publisher when her husband died in 1980.

Under her leadership, the paper expanded its arts, education, political, and human interest coverage, adding both advertising and editorial staff. She presided over several redesigns of The Star, the first in 1985, when it turned 100, and another that introduced color photographs to its pages, a change that sparked great consternation among some longtime readers of the venerable broadsheet.

In a 1985 article published on the occasion of the paper's 100th anniversary, Ms. Silverman described Ms. Rattray as "a perfectionist" and said "she tries to read every word of every issue before it goes to press, often into the wee Thursday morning hours, when she also checks camera-ready pages to make certain the headlines are on the right stories and have been pasted in straight. She suffers errors, whether of omission or commission, innocent or incompetent, badly, and criticism of The Star hardly at all."

"If you think about the period of time in which she took over and all the changes and growth that took place on the South Fork, it really, under her tenure, went from a small-town newspaper to something more sophisticated and more complicated," David Rattray said. "She raised the three of us, managed the business side of this thing, and sat in the editor's chair during that period of unprecedented growth here. That was her overarching accomplishment." He said he marvels at how she managed to do it and has come to realize it was through sheer "force of will."

"She always used to talk about zoning and how the fight to preserve some semblance of this place really comes down to the little decisions on the individual properties. There was no story too small for her," he said.

In the 1980s, Ms. Rattray had wanted to buy The Sag Harbor Express, but when a deal failed to materialize, she instead started a paper of her own in the village. The Sag Harbor Herald operated out of a building at the intersection of Main and Madison Streets from 1988 to 1992. It was during that period that Arthur Carter, then the publisher of The New York Observer, became a shareholder in The Star. Eventually, the paper reverted to full family ownership.

"Back in the '80s, going out to dinner with Helen was like being in the company of a movie star," Ms. Silverman wrote. "At Cafe Max, 1770 House, or Della Femina's (where her caricature was prominently featured on a wall of local grandees), the maitre d' would come running over: 'Good evening, Mrs. Rattray, so nice to see you. . . .' She would nod graciously; she was loving it. Years later, after hedge funds and Hollywood discovered East Hampton, she'd remark sadly that no one knew who she was anymore."

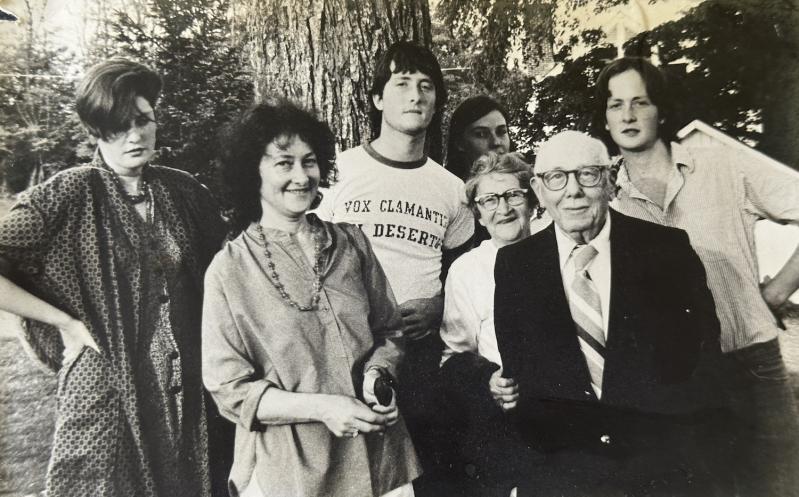

Her large circle of friends included the feminist writer and activist Betty Friedan, Victor Rabinowitz, who had been a lawyer for Fidel Castro's government, the publisher Barney Rosset, Gordon Gould, one of the inventors of the laser, and many prominent artists, writers, and political figures.

Though she rarely took vacations while running the paper, she found time to sail on Gardiner's Bay. She loved gardening and knew the Latin names of all of her flowers. She also enjoyed cooking and entertaining. Hundreds attended her Fourth of July parties on the beach in front of her house at Promised Land and there were often 30 people at Thanksgiving dinners, her daughter recalled.

Ms. Rattray was one of the founders of the Hampton Day School in Bridgehampton with her longtime friend Tinka Topping and a group of other parents, and she sent her children there.

Her love of music, particularly classical and choral music, was a constant in her life, and dinner parties would often end with singing around a piano in the living room. She traveled to New York City to take opera lessons and sang soprano with the Choral Society of the Hamptons for decades. She was a lifelong fan of Frank Sinatra and considered him "the only acceptable popular singer," her daughter said.

Her second husband, Christopher Thayer Cory, whom she married in 1995, shared her love of music and also sang with the Choral Society.

They enjoyed sailing and traveling together when Ms. Rattray's schedule finally allowed for it. In 2019, as their health began to decline, the couple moved to Peconic Landing in Greenport. Mr. Cory survives.

Her daughter lives in East Hampton, David Rattray lives in Amagansett, and Dan Rattray lives in Springs. Also surviving are her grandchildren: Adelia H. Rattray and Sky V. Rattray of New York City, Everett R. Rattray and Ellis Rattray of Amagansett, and Nettie T. and David T. Rattray of East Hampton. Her grandson Raymond Rattray died in 2024.

Ms. Rattray was buried on Saturday at Cedar Lawn Cemetery in East Hampton. A celebration of her life will be held on Sunday at 11 a.m. at Ashawagh Hall in Springs, with a potluck lunch to follow. It will be an opportunity to reflect on Ms. Rattray's life and "the importance of the free press," her family wrote.

With Reporting by Irene Silverman