As a student at Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts, Thomas Gilbert Jr., who recently began serving a 30-year prison sentence for murdering his father, joined Big Brothers Big Sisters, a community-based mentoring program. A Princeton graduate who grew up spending summers and vacations in the Georgica Association in Wainscott, he was assigned an 8-year-old boy from Deerfield Township, and they formed a connection.

“We met him and his parents,” recalled Shelley Gilbert, Thomas’s mother. “They were waxing eloquently about how much Tommy had done for him and we were doing likewise, waxing eloquently about how wonderful their son was and how much he had done for Tommy.”

| This is the second installment of a three-part story. The third part will be published next week. |

Tommy surprised them, she said, when he signed up for a confirmation class at Deerfield. They’d enrolled him in a class at their church in the city while he was at the all-boys Buckley School, but he dropped out. “Eighth grade at Buckley is notorious,” his mother said. “People who graduate with honors from Ivy League schools talk about eighth grade being the toughest academic year. So he did not go on to that, but he did when he got to Deerfield.”

Religion was important to the family, she said, though they were not regular churchgoers. “Kindness and good citizenship and whatnot were important to all of us,” she said. The Gilberts attended their son’s confirmation ceremony at an Episcopal church near the Deerfield school. “We went up to a lovely ceremony. I was surprised and pleased.”

Before his senior year, she remembered, the dean of students asked Tommy to be a proctor for the freshman-sophomore dorm. “That’s how highly thought of he was throughout the school, among the administrators, coaches, teachers, faculty.”

He took heavy course loads — four A.P. courses in senior year — while playing varsity football, basketball, and baseball. His parents often traveled up to Massachusetts for games. Tommy was never one to brag, she said. “In twelfth grade, when I congratulated him on achieving his goal of trivarsity, he said, ‘Oh, my goal was to do it junior year. I didn’t achieve that goal.’ ” When he was one of two Deerfield boys chosen for an All-New England team, the Gilberts heard about it from another boy, not their son.

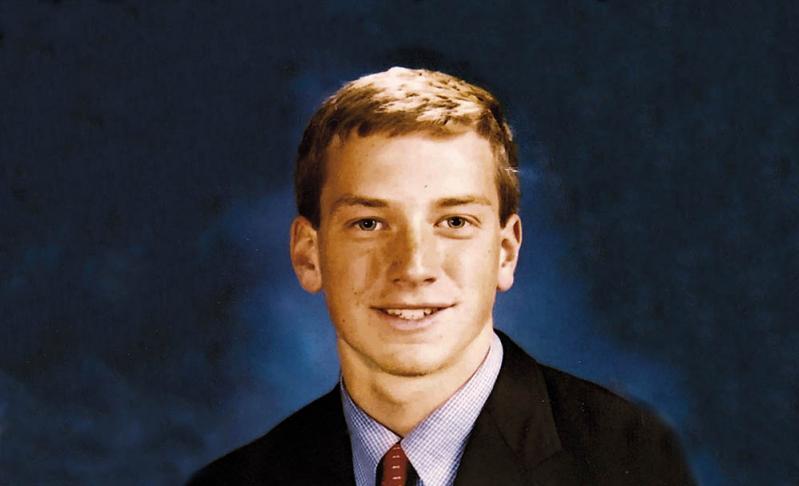

Courtesy of Shelley Gilbert

The cherry on top was early admission to Princeton, his father’s alma mater. Ms. Gilbert said it was a school that suited their son perfectly, from location to class size. She read with pardonable pride from his advisor’s report in June 2002: “Tommy has a positive, upbeat attitude, a terrific sense of humour, a calm unflappable manner, growing confidence, and a sound sense of self.”

But his odd behavior was just beginning to show itself. “Comes on slowly, hard to spot — very hard,” his mother said. Her husband noticed first. Tommy became very quiet, she said. “We talked about it. I thought it was just exhaustion, well-deserved exhaustion.” His father, though, “thought it was more than that.”

At first, there were warning signs of O.C.D., obsessive-compulsive disorder, characterized by unwarranted fears that lead to uncontrollable behavior. The fear of germs, for example, is typical. Their son started to avoid certain objects, Ms. Gilbert said. Then he claimed they were “contaminated.” Later, he said their entire apartment, on Beekman Place in Manhattan, was contaminated.

The parents offered help, but he resisted. By the time he agreed to see a psychiatrist he was legally an adult, and the recommendation was that he be hospitalized. “By the time you start getting a handle on it, they’re 18,” his mother said. “And it’s not just us. It’s very common.”

She and her son were close. “I could read him like an open book, which was great fun. I loved it, and I could get through to him remarkably well, especially for the parent of a teenager,” she said. Then, however, “the road map changed. Suddenly, I’m dealing with a stranger.”

Her son got worse at college. He used illegal drugs — everything from marijuana to hallucinogenic mushrooms and LSD, court and medical records showed. His mother called it “self-medicating,” which she said was not uncommon. Mr. Gilbert sought help for insomnia at one point, and spent a night in a hospital, but then checked himself out. He ended up alone in a hotel room in South Carolina, speaking, court records show, only to cab drivers and doctors.

His parents could have gone the route of involuntary hospitalization, but it could not be indefinite. A 72-hour emergency hold at a psychiatric facility and he would be out. “It is bad enough having a mentally ill child on your hands. It is worse to have an angry mentally ill child,” his mother said.

After Mr. Gilbert started running into trouble with the police, however, the Gilberts hired an attorney, Alex Spiro, who, before going into law, had worked at McLean Hospital, a top-rate psychiatric hospital affiliated with Harvard Medical School. Mr. Spiro held out little hope that a court would order long-term institutionalization for their son. Unless someone is of imminent harm to himself or someone else, he explained, he cannot be involuntarily committed. Here was this tall, handsome, smart, well-dressed surfer. “ ‘What could possibly be the matter?’ ” he said in an interview with The Star rhetorically “He’s faking well.”

He was, in some settings, not in others. There was a fight with a friend, Peter Smith Jr., who won an order of protection against him and testified at the trial that Mr. Gilbert had tried to kill him after the friendship soured. Then there was a fire that destroyed the Smith family’s centuries-old house in Sagaponack. Arson was suspected, and Thomas Gilbert Jr., though never charged, was the prime suspect.

When Ms. Gilbert heard the accusation that her son had set the Smiths’ house on fire, she was horrified. He had never been violent in any way, she said.

But he did have pending charges, and after he killed his father, about four months after the Sagaponack house fire, Mr. Spiro told the Gilberts that the burden should have been on the criminal justice system to require mental health conditions. “It really could have been a blessing in disguise,” he said.

“If New York State had provided the necessary help, my husband would be alive,” Ms. Gilbert said. She and her husband had discussed hospitalization with him over the years, but he resisted. At one point they had papers drawn up for him to sign to enter a private hospital. When he worried what his friends would say if they found out, the couple came up with a story that he was surfing off the coast of Africa for a month. He never signed the papers.

“People need to understand what needs to happen when somebody’s going through this, so they can get help early,” Ms. Gilbert said. Teenagers need to know how to spot the signs in their classmates, she said. Schizophrenia typically presents in the late teens and early 20s.

“Just as early detection has been a huge factor in cancer success, it needs to be that in mental health as well, which means the stigma needs to go. The more we talk about it, the less stigma there will be,” Ms. Gilbert said.