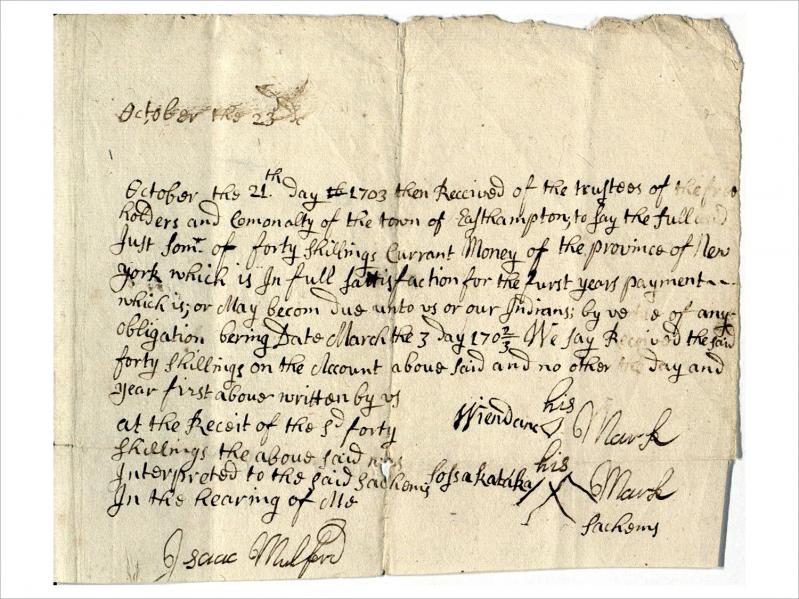

This receipt, dated Oct. 21, 1703, records the first annual payment by East Hampton settlers to the Montaukett people. The payment amounted to a rental fee for the use of grazing lands on the Montauk peninsula.

Attached to the receipt was a list of grazing land shares claimed by English settlers. The terms of the payment were established on March 3, 1703, which the receipt references. The settlers paid the Montauketts 40 shillings, or 2 pounds (at most roughly $67,700 today), in rent.

Two Montauketts “signed” the documents, making their marks: “Sassakataka” and “Wiendanc,” who are identified as “Sachems,” or tribal leaders. According to John A. Strong, a former Southampton College professor and expert on Montaukett history, the latter meant Wyandanch, although he notes that this Wyandanch was not the Montaukett leader of the same name who dealt with Lion Gardiner (1599-1663), but a descendant who assumed the name after becoming sachem. Sassakataka’s tribal role seems closer to counselor.

The March 1703 agreement emerged in the context of tensions over destruction caused by sheep grazing in 1701, which prompted Wyandanch and Sassakataka to negotiate a sale of this land to outside investors in 1702. That deal guaranteed permanent residential rights to the Montauketts for the area east of Lake Montauk. The East Hampton Town Trustees objected to this plan, pressuring a group of Montauketts to reject it.

Ultimately, the town got its way, determined to prevent future threats to the Montauk land. On March 3, 1703, the town created a series of four documents that the Montauketts were forced to sign. The documents denied the authenticity of the 1702 deal and reinforced the town’s claim to the land. The agreements also required an annual payment to the Montauketts for the land.

Finally, the Montauketts were required to pay a steep fine if they ever tried to sell Montauk land to a third party.

Andrea Meyer, a librarian and archivist, is head of collection for the East Hampton Library’s Long Island Collection.