“An attic in East Hampton, Long Island, New York, contains a wealth of archive material about the Dutch resistance,” begins a May 2023, front-page article in Trouw, a Dutch publication that was founded as an underground newspaper during World War II.

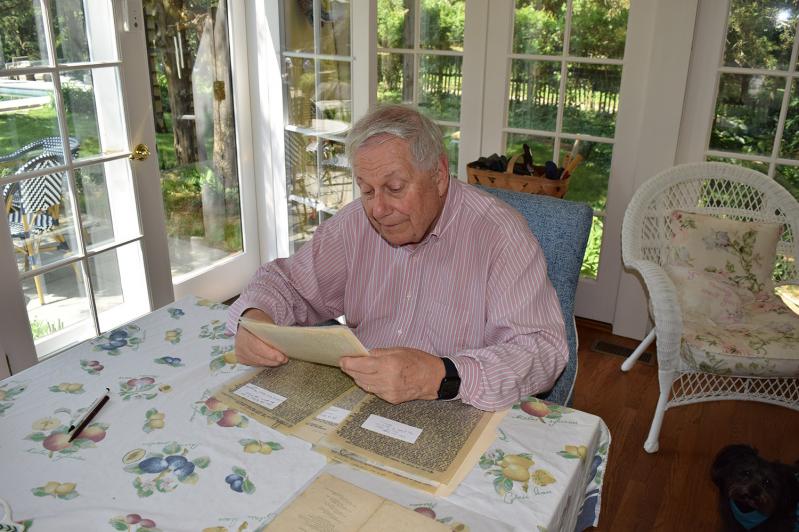

That attic is in the Springs house of Alice and John Tepper Marlin, where many of some 500 boxes of documents, among them “letters from women to women” during the war, are stored, Mr. Tepper Marlin said. They are the personal archive of his mother, the renowned children’s book author Hilda van Stockum, who wrote and illustrated almost 20 books including “The Winged Watchman” and “The Borrowed House,” both set in Holland during World War II.

Much of the archive is correspondence among women relatives who lost husbands, sons, brothers, and other relatives during the war. Van Stockum, who died in 2006, translated some of the letters into English. The feature in Trouw focuses on women in the Dutch resistance, a topic Mr. Marlin, a former chief economist and senior policy adviser for the City of New York, said had heretofore been neglected. The author of the feature in Trouw “was very interested in the fact that there’s new stuff that they don’t have that relates to women in the resistance and before and after the resistance,” he said.

The letters bring to life the crushing, cruel realities of World War II and of living under a hostile occupying force. “My dear Olga,” one, dated June 17, 1945, begins. “Ever since we heard through Alfred de Booy that you lost your dear eldest son Willem in this war, my thoughts have been often with you.” Olga Boissevain van Stockum was Mr. Marlin’s grandmother; Willem was his uncle. The letter’s author, Nella Boissevain Hissink, was Olga’s younger sister and the mother-in-law of Walraven van Hall, a banker and leader of the Dutch resistance who was executed by the Nazis in 1945. Boissevain Hissink’s own son was also killed during the war.

“Dear,” the letter continues, “he was a son to be proud of in times of peace and in wartime. What a sadness all around us.” In addition to their own trauma during the Nazi occupation, women “had the pain of their husbands, sons, parents,” Mr. Marlin said.

He recently completed an English translation of “Walraven van Hall: Premier Van Het Verzet (1909-1945),” a biography by Erik Schaap. Though he is able to translate one language to another, “my mother and my grandmother didn’t want me to speak Dutch, because they spoke about the war and didn’t want me to get upset,” he said.

“Van Stockum’s mother came from the well-known Boissevain resistance family,” reads the feature in Trouw. “Walraven van Hall, about whom a film appeared in 2018, was her cousin. His mother and mother-in-law sent many letters to the United States.” (“The Resistance Banker” was the most-watched Dutch film of 2018.)

Trouw itself played an important role in the resistance. Considered illegal during the occupation, it also paid a heavy price, with many involved in its production and distribution murdered by the Nazis. “Before the war, everything was organized by religion — the Catholics, different Protestant denominations, and a Jewish component, which was why it was so easy for the Nazis to track them,” Mr. Marlin said. “There were 15 underground newspapers of size. They were mostly on the left, progressive. Trouw is the only one of any size that was on the right, meaning religious-based.” At its founding, it represented Protestant church adherents, he said.

“What I’m very interested in is the issue of collaboration and resistance as a spectrum,” Mr. Marlin said. “The Dutch are going to reveal, next year, the names of 300,000 accused collaborators. They’re not saying they were guilty or not, they’re saying someone accused them and the names should be public so that we can look at the historical record. But there are 300,000 — that’s a lot in a relatively small country. On the other hand, there were probably 300,000 resisters.”

“To me, it’s all very exciting,” he said, “because all this is coming to life, because I know about all these things now. By translating Walraven van Hall’s life story, with the names of all the people, now I know who they are.”

Mr. Marlin, who has been in Europe for most of this month, recently arrived in Stockholm. Tomorrow, he will present “Deadly Games: Nazi Terror and the Dutch Resistance, 1940-45,” which he described as a paper on his translation of the biography of Walraven van Hall, at the 26th Annual International Conference on Economics and Security, co-hosted by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute and the Swedish Defence Research Agency. He describes it as an exploratory paper that seeks to make the case that studying the Dutch resistance can generate useful guidance today, referring to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the complexities of occupied lands where allegiances can abruptly shift depending on conditions on the ground.

“It’s to a group of economists,” he said of the paper, “and I’m trying to give them the idea that there’s a bell curve. On one end is a small number of people who totally commit themselves to resisting. On the other end are a bunch of people who totally commit themselves to collaborating. But most people are in the middle, and it’s a bell curve. These people” — the resistance — “risked their lives. And a lot of them died.”