Book Markers: 02.26.15

Book Markers: 02.26.15

The Quotation Game

Spurred by a not very Long Island-like deep cold and unusual masses of snow — in short, a long winter indoors — your friendly neighborhood bookseller has started a diverting game, a “literary treasure hunt” called SmartyPants. Every day BookHampton will post a quotation on its website and Facebook page, and then the stabs at identification of both it and the book it’s from can begin.

“Everyone who identifies the quotation wins a prize,” a release said. No strings attached, though players do have to stop in at either the Main Street, East Hampton, or Hampton Road, Southampton, shop to claim winnings — maybe a book, maybe a gift certificate, maybe chocolate.

More Than a Chance to Suck Up

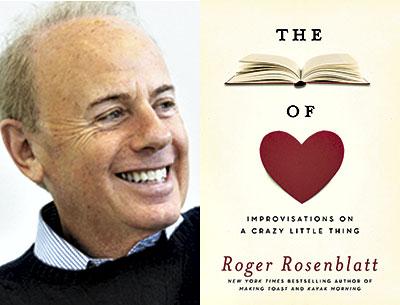

Wednesday brings the Faculty Five to a frozen Stony Brook Southampton campus to read from their work — new, old, whatever they please. The speakers are: Lou Ann Walker, the editor in chief of The Southampton Review and the author of the award-winning memoir “A Loss for Words,” Susan Scarf Merrell, the fiction editor of that journal, whose latest book is “Shirley: A Novel,” Roger Rosenblatt, the esteemed essayist just out with “The Book of Love: Improvisations on a Silly Little Thing,” the novelist Ursula Hegi, and Julie Sheehan, the poet who directs the M.F.A. program in creative writing and literature.

That program, of course, sponsors the Writers Speak series, which happens most Wednesdays through May 6 in Chancellors Hall starting at 7 p.m.