The Man and the Memories

The Man and the Memories

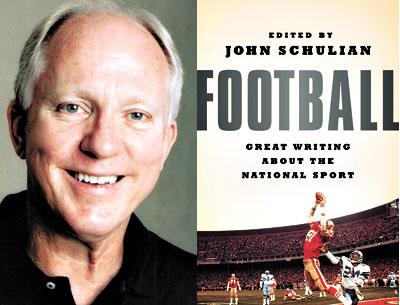

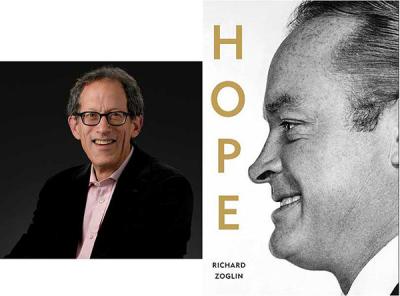

“Hope: Entertainer

of the Century”

Richard Zoglin

Simon and Schuster, $30

Fred Astaire, it was said, gave Class to Ginger Rogers and Ginger gave Fred Sex. Another song-and-dance man gave the whole nation Hope. And in return the nation gave its heart to Leslie Townes (Bob) Hope. Streets, schools, hospitals, and arts centers all across America are named after him, even a bridge (in Cleveland) and an airport (in Burbank, Calif).

At one point or another in the last century, the British-born, Cleveland-raised Hope was a king of every entertainment medium from vaudeville through Broadway to Hollywood and TV, notably combining the latter two worlds this time of year as the wisecracking host of Academy Awards TV shows for a record 19 times. He was the world’s “most honored entertainer” in the Guinness book of records.

Also like Astaire, unlikely as it seems, through his many Broadway shows and Hollywood musicals, Bob Hope helped introduce many of the popular songs by Kern, Porter, Berlin, Cahn, Loesser, Lane, and others that are now considered standards. Among them, of course, “Thanks for the Memory.” But also “Two Sleepy People,” “De-Lovely,” “I Can’t Get Started,” “Buttons and Bows,” “Silver Bells,” “You Do Something to Me,” and “You’ve Got That Thing.”

Balancing the American cockiness of a George M. Cohan and the kind of studied self-deprecation later exploited by Woody Allen (who admits to studying him closely), the quick-witted (but generally ghostwritten) Hope helped cheer the nation through the Depression’s hard times and war times from Europe and the Pacific to Korea and Vietnam.

His tireless travel to packed personal appearances at home, to support U.S. troops abroad — and to burnish his international brand — may well have led him to be seen live by more people in more places than any other person in history.

So writes Richard Zoglin in his exhaustive — but far from exhausting — biography “Hope: Entertainer of the Century.” A veteran Time magazine writer, Mr. Zoglin considers both Hope’s comedy — often funnier because of his delivery than the jokes themselves, he concludes — as well as contradictions in the man behind the merriment.

Hope also set a new mark for entertainer involvement in causes beyond career, Mr. Zoglin notes, though he would hardly agree with all the antiwar or anti-establishment goals so many activist artists later pursued. In 1941 he was awarded the first of five honorary Oscars as “the man who did most for charity.”

So why are we surprised Hope was so significant so long to so many? Perhaps because unlike other stars of the 20th century whose fame outlived them — Cohan, Marlon Brando, Ethel Merman, Frank Sinatra, and Hope’s “Road” movie screen mate Bing Crosby — Hope had the misfortune to outlive his celebrity while still performing, even in the last decade before his death at age 100 in 2003.

As Mr. Zoglin explains, Hope created or at least perfected the stand-up monologue — with a team of writers crafting timely if gentle zingers. But he began to seem anachronistic as culture and politics changed. Comics and commentators could say practically anything about anyone, and the sharper the better.

Sadder still, the true patriotism that took Hope to the troops — and to the presidents who put them in harm’s way — also made him politically incorrect to many as the nation moved from the Good War to a split over Vietnam and increasingly venomous ideological lines.

Fortunately for Hope, his long life and legend were not seriously shadowed by an ever more bloodthirsty tabloid journalism in print, on screen, and online.

Ultimately one of Hollywood’s wealthiest, through real estate and other wise investments, he downplayed his fortune to retain a common touch and connection to audiences — rarely refusing to sign an autograph, often writing personal answers to fan mail. But “his personality had an essential coldness,” Mr. Zoglin writes.

And he was notoriously demanding of the many writers and image-promoters he employed. “Once you worked for Hope you were his property and just on loan to the rest of the world,” said Hal Kanter, one of his wordsmiths over four decades.

Though married to a former nightclub singer, Delores DeFina, for a remarkable 69 years, Hope also was known to associates as a determined womanizer, including a romance with the actress Marilyn Maxwell so long-running that some around Hollywood called her “Mrs. Bob Hope.”

Of all Hope’s reported liaisons, however, Mr. Zoglin ranks one with Merman as among the unlikeliest. After some distracting shenanigans onstage in their 1936 show “Red, Hot and Blue,” Merman recalled warning the producer: “If that so-called comedian ever does that again, I’m going to plant my foot on his kisser and leave more of a curve in his nose than nature gave it.”

But Mr. Zoglin found an unpublished memoir by Hope’s longtime publicist, Frank Liberman, that reported Bob and Ethel often walked home from the show and made love “in darkened doorways on Eighth Avenue” before going their separate ways.

Of course Hope’s best-known connection was with Crosby, though Mr. Zoglin says they never really socialized. Hope had gotten good reviews on Broadway when in 1932 he was asked to M.C. a two-week show at the Capitol Theatre headlined by the fast-rising young crooner, already a far bigger star with his own radio show and a Hollywood contract.

But the two worked well together, creating vaudeville-style bits between the songs. “The gags weren’t very funny, I guess,” Mr. Zoglin quotes Hope saying, “but the audience laughed because Bing and I were having such a good time.” Not enough to follow him west, however.

Publicly, at least, Hope preferred show business in New York over the lure of Hollywood, where he had failed a screen test some years earlier. But in 1937 he finally gave in to an offer from Paramount Pictures, perhaps only temporarily. “This may not be permanent — probably won’t be,” Hope told a reporter before heading to make his first movie. Ha!

That film, “The Big Broadcast of 1938,” gave Hope a whole new career, and even the infinitely adaptable theme song for it — “Thanks for the Memory” — in a shipboard scene with Shirley Ross that had her in tears after it was shot, along with the song’s creators, Leo Robin and Ralph Rainger. “We didn’t know we wrote that song,” Mr. Zoglin reports them saying.

“Broadcast” also brought Hope and Crosby back together for lunches, golf, radio shows, and a special Hollywood night at the Del Mar racetrack near San Diego where Crosby, a part owner, as master of ceremonies called Hope to the stage for a replay of their Capitol Theatre chemistry. It so impressed the Paramount production chief there that he decided they should make a movie together.

It was “Road to Singapore,” originally planned as “Follow the Sun” for Crosby, then as “Road to Mandalay” for Jack Oakie and Fred MacMurray, and re-titled again for Crosby, Hope, and the darkly beautiful Dorothy Lamour, whom Hope had heard as a singer back in New York.

Once again their off-the-cuff chemistry was king. “Hope and I tore freewheeling into a scene, ad-libbing and violating all of the accepted rules of movie-making,” sometimes talking right to the audience, Crosby recalled.

“The ‘Road’ pictures had all the excitement of live entertainment,” Hope said.

Many more roads followed: six more comic adventures with Crosby, more than 70 features and shorts altogether, plus Hope’s own endless travels around the world and into the homes of millions via radio and television. But after decades of dominating all forms of entertainment, things were not going so well by 1972, when Hope’s final film comedy was a flop, albeit aptly titled: “Cancel My Reservation.”

A maddening mess to make — from a serious Louis L’Amour novel that Hope had optioned — it was “no better than it deserved to be,” writes Mr. Zoglin. “The mix of comedy and murder-mystery might have worked twenty or thirty years before, when Hope could do that sort of thing in his sleep. Now he actually does look asleep.”

“Bob Hope on the Road to China,” a 1978 TV special, “was more of a diplomatic triumph than an entertainment one,” says Mr. Zoglin. But as anti-Vietnam anger faded, Hope kept tending to his brand and drew renewed praise for his body of work. “Oh, go on, highbrows . . . look at what America thought was really funny,” Peter Kaplan wrote in New Times magazine.

By the start of the 1980s, however, age was starting to wear Hope down, Mr. Zoglin writes, though reporting that his dance card for 1983, as he turned 80, included 86 stage shows, 42 charity benefits, 15 TV commercials, 14 golf tournaments, 11 TV guest appearances, and 6 NBC specials.

But his ratings were up and down, and by the late ’80s his increasing deafness (“I can still hear the laughs,” Hope insisted) and other physical decline were evident “even to casual viewers.” And lettering on the cue cards kept getting bigger so Hope could read them.

He got testy with staff and fellow stars. “If I ever end up like that, guys, I want you to shoot me,” Johnny Carson told his writers. After another Hope Christmas special, David Letterman told Rolling Stone, “If it had been a funeral, you would have preferred the coffin be closed.”

After his final NBC special, “Laughing With the Presidents” in 1996, at occasional charity benefits and ceremonial events Hope appeared disoriented. And he was downright disruptive at a New York cabaret show starring his wife and an old friend, Rosemary Clooney. At home there was “Jeopardy!” on TV (with headphones) and a few holes of golf before becoming virtually bedridden.

For his 100th birthday in May 2003, Hope received cards from President George W. Bush, Queen Elizabeth, and more than 2,000 others. Two months later he died peacefully of pneumonia — “officially,” Mr. Zoglin writes (suggesting otherwise). “Even his long, long goodbye was somehow inevitable and fitting. Hope needed to keep performing because he couldn’t stop believing that the audience needed him.” And all those memories.

David M. Alpern, creator of the “Newsweek on Air” and “For Your Ears Only” radio shows, now hosts podcasts for World Policy Journal from his home in Sag Harbor.

Richard Zoglin, theater critic for Time magazine, has a house in Wainscott.