Book Markers: 11.06.14

Book Markers: 11.06.14

Thinking Differently

David Flink, a founder of Eye to Eye, a national mentoring program, is not only an expert in learning disabilities, he has had his own struggles with them, specifically dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Now, he’s bringing all of that background to the East Hampton Library in a program for parents. Called “Thinking Differently: Reframing Learning for a New Generation,” it starts at 3:30 p.m. on Saturday.

In his new book, “Thinking Differently: An Inspiring Guide for Parents of Children With Learning Disabilities,” he explains the difficulties and diagnoses, and offers strategies for how parents can be the best possible advocates for children. Building self-esteem and remaking the learning environment are also addressed.

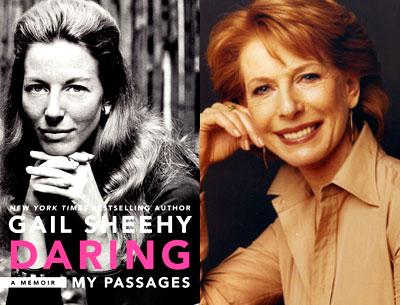

Women Voters Host Sheehy

A lit lunch on the Shinnecock Canal? Not a bad afternoon. Cowfish restaurant in Hampton Bays will be the site of the League of Women Voters of the Hamptons’ fall author lunch on Friday, Nov. 14, from noon to 3 p.m., with Gail Sheehy discussing her new autobiography, “Daring: My Passages.” It details her work at New York magazine during its 1970s heyday, the splash she made with the hit book “Passages,” and her relationship with the influential magazine editor Clay Felker. Copies will be available for purchase and signing.

The lunch, including a three-course meal, costs $60. R.S.V.P.s are due by Monday, and checks made out to L.W.V. Hamptons can be sent to Gladys Remler at 180 Melody Court, Eastport 11941. The number to call with questions is 288-9021.